http://www.economist.com/news/united-states/21603078-why-thieves-love-americas-health-care-system-272-billion-swindle

INVESTIGATORS in New York were looking for health-care fraud hot-spots. Agents suggested Oceana, a cluster of luxury condos in Brighton Beach. The 865-unit complex had a garage full of Porsches and Aston Martins—and 500 residents claiming Medicaid, which is meant for the poor and disabled. Though many claims had been filed legitimately, some looked iffy. Last August six residents were charged. Within weeks another 150 had stopped claiming assistance, says Robert Byrnes, one of the investigators.

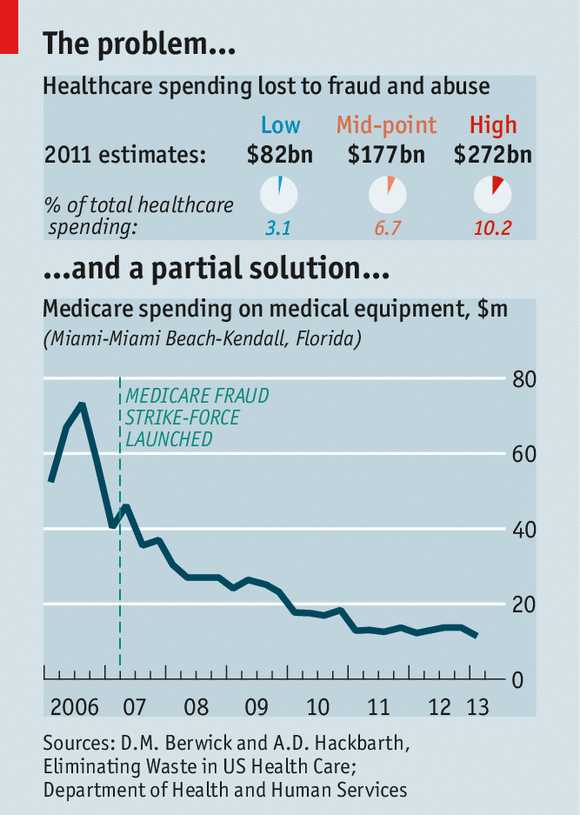

Health care is a tempting target for thieves. Medicaid doles out $415 billion a year; Medicare (a federal scheme for the elderly), nearly $600 billion. Total health spending in America is a massive $2.7 trillion, or 17% of GDP. No one knows for sure how much of that is embezzled, but in 2012 Donald Berwick, a former head of the Centres for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), and Andrew Hackbarth of the RAND Corporation, estimated that fraud (and the extra rules and inspections required to fight it) added as much as $98 billion, or roughly 10%, to annual Medicare and Medicaid spending—and up to $272 billion across the entire health system.

Federal prosecutors had over 2,000 health-fraud probes open at the end of 2013. A Medicare “strike force”, which was formed in 2007, boasts of seven nationwide “takedowns”. In the latest, on May 13th, 90 people, including 16 doctors, were rounded up in six cities—more than half of them in Miami, the capital city of medical fraud. One doctor is alleged to have fraudulently charged for $24m of kit, including 1,000 power wheelchairs.

Punishments have grown tougher: last year the owner of a mental-health clinic got 30 years for false billing. Efforts to claw back stolen cash are highly cost-effective: in 2011-13 the government’s main fraud-control programme, run jointly by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Department of Justice, recovered $8 for every $1 it spent.

As fraud-fighting has intensified, dodgy billing has tumbled in areas that were most prone to abuse, such as durable medical kit and home visits (see chart). Home-health fraud—such as charging for non-existent visits to give insulin injections—got so bad that the CMS, which runs the programmes, called a moratorium on enrolling new providers in several large cities last year. Since tighter screening was introduced under Obamacare, the CMS has stripped 17,000 providers of their licence to bill Medicare. Thousands of suppliers also quit after being required to seek accreditation and to post surety bonds of $50,000.

Yet the sheer volume of transactions makes it easier for miscreants to hide: every day, for instance, Medicare’s contractors process 4.5m claims. In this context the $4.3 billion recovered by fraud-busters in 2013, though a record, looks paltry.

Better than cocaine

Fraud migrates. Take one popular scam: overbilling for HIV infusion, an outdated therapy that Medicare still covers despite the existence of cheaper, better alternatives. This scam waned in Florida after a crackdown, only to pop up in Detroit, run by relatives of the original perpetrators.

Fraud mutates, too. As old hustles are rumbled, fraudsters invent new ones. “We’ve taken out much of the low-hanging fruit,” says Gary Cantrell, an investigator at HHS—an example being the thousands of bogus equipment suppliers registered to empty shopfronts. Scams now need to be more sophisticated to succeed, he argues. Doctors, pharmacies, and patients act in league. Scammers over-bill for real services rather than charging for non-existent ones. That makes them harder to spot.

Some criminals are switching from cocaine trafficking to prescription-drug fraud because the risk-adjusted rewards are higher: the money is still good, the work safer and the penalties lighter. Medicare gumshoes in Florida regularly find stockpiles of weapons when making arrests. The gangs are often bound by ethnic ties: Russians in New York, Cubans in Miami, Nigerians in Houston and so on.

Stealing patients’ identities is lucrative. Medical records are worth more to crooks than credit-card numbers. They contain more information, and can be used to obtain prescriptions for controlled drugs. Usually, it takes victims longer to notice that their details have been pinched. The Government Accountability Office has recommended that the CMS remove Social Security numbers from Medicare cards to prevent fraud. It has yet to do so.

In one fast-growing area of fraud, involving pharmacies and prescription drugs, federal investigators have seen caseloads quadruple over the past five years. Elderly patients may receive kickbacks to sell their details to a pharmacist. He will then provide them with drugs they need while billing Medicare for costlier ones.

Paid recruiters scour nursing homes for accomplices. Some pharmacies also pay wholesalers to produce phoney invoices. Others bribe medical workers for leftover pills: in April a pharmacy-owner in Louisiana admitted to paying nursing-home staff a few hundred dollars a time to bring her unused drugs, which she repackaged and sold as new, billing Medicare $2.2m for the recycled meds between 2008 and 2013.

Another scam is to turn a doctor’s clinic into a prescription-writing factory for painkillers (or “pill mill”) and resell them on the street. A clinic in New York was recently charged with fraudulently producing prescriptions for more than 5m oxycodone tablets, which were sold locally for $30-$90 each. The alleged conspirators included doctors and traffickers who ran crews of “patients” so large that long queues sometimes formed outside the clinic. The doctors charged $300 per large prescription. One raked in $12m. To cover their backs they would ask for scans or urine samples purporting to show injuries. The fake patients typically obtained these from the traffickers at the clinic door.

False billing by pharmacies is rife. New York’s Medicaid sleuths have stepped up spot checks to see if the drugs in the back room square with invoices. But this is a lot of work, so most outlets are never checked.

Dozens of operators of ambulances and ambulettes (vans designed to take wheelchairs) have been caught offering kickbacks to patients to pretend they can’t walk. This lets them qualify for “emergency” pick-ups, for which the company can charge $400 per patient. New York has clamped down with roadside checks. But in one case, word that a checkpoint had been set up spread so quickly—as drivers called each other and a local Russian-language radio station put out a warning—that the number of ambulettes on the main street “went from several to none in a few minutes as they re-routed down side streets”, says Chris Bedell, who took part.

This sort of pavement-pounding investigative work remains important. Another approach is the “desk audit”, where possible overpayment is identified but the only way to ascertain losses is to sift through heaps of records manually. Florida’s Agency for Health Care Administration (AHCA) has recovered up to $50m a year solely from hospitals billing for treatment of illegal aliens that is wrongly coded as “emergency care”. But the work is labour-intensive. Data-crunching technologies are increasingly being used to complement the human eye. “When I started in 1996 we had little access to data,” says HHS’s Mr Cantrell. “It had to be requested ad hoc from CMS contractors.” Now a central database houses near-real-time information for Medicare. This helps the 300 workers at the inspector-general’s office who are trained in data analytics to “triage” the tips that flow in. “We receive far more than we can investigate closely,” says Mr Cantrell.

The CMS is still getting to grips with a new predictive-analysis system, which was introduced in 2011 to catch Medicare fraud earlier and is modelled on tools used by credit-card firms. This identified $115m of dodgy payments in 2012, its first full year. (The number for the second year has yet to be released.) Another useful tool is voice-recognition technology. In Florida, health workers who conduct home visits have to call in from the patient’s phone during each appointment to have their voice pattern matched against the one stored electronically. This has greatly reduced billing for non-visits.

Technology is no panacea, however. Medicare’s computers were pumping out thousands of payments a year for patients who had been struck off the programme before receiving their treatment, until human hands began to intervene this year. The electronification of patient records can allow “cloning”, in which treatments automatically trigger excessive billing codes by defaulting to set templates.

This is the medical world’s “dirty secret”, says John Holcomb of the Texas Medical Association. Everyone talks about it in the doctor’s lounge, but few complain. (What doctors do complain about is the complexity of the bill-coding system: see article.) Moreover, there are gaps in the data picture—some of which could grow. Federal investigators complain that there is no proper national repository for Medicaid information, which is held state-by-state.

A bigger worry is that, as ever more Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries move to “managed care” (privately administered) plans, government sleuths will have access to less data. This could lead to lower fraud-related recoveries.

Efforts have been made to improve information-sharing between government and private insurers, including the creation of a public-private forum, the National Health Care Anti-Fraud Association (NHCAA). But some insurers are reluctant to take part, fearing that being too open with their data would invite lawsuits over privacy. Fraudsters bank on public and private payers not working together to connect the dots, said Louis Saccoccio, the head of the NHCAA, at a recent hearing.

The NCHAA is pushing for federal immunity guarantees for insurers that share fraud-related information. On May 20th a bipartisan group of senators introduced a bill to make it easier for insurers to share data with Medicare. It would also require Medicare to check new providers for links to firms that have previously swindled the taxpayer (which you might have thought it was already doing).

Obamacare has had a big impact, says Shantanu Agrawal of the CMS. One thing it requires is that when a state kicks out a dodgy Medicaid provider, it shares that information with Medicare, and vice versa. Previously there were legal impediments to doing this, for some reason.

Resources are tight for investigators. New York has a Medicaid investigations division of 110 souls (including support staff) to scrutinise $55 billion of annual payments and 137,000 providers. Gloria Jarmon, an auditor with the HHS, told a recent hearing that budget cuts will probably force it to cut its oversight of Medicare and Medicaid by 20% in this fiscal year. “Everyone [in Congress] is excited that we bring in eight times more than we cost, but that hasn’t translated into more funding,” laments Mr Cantrell.

This squeeze makes it all the more important to enlist help. More than 5,000 old folk have joined “Medicare patrols”, which hold local meetings to raise awareness of common scams. A crucial part of the anti-fraud effort is the new, simpler Explanation of Benefits (summary statement) that lets recipients see who has billed the programme with their identification numbers. This is “a landmark change”, a CMS executive told Congress last year, adding: “Our best weapon in fighting fraud is our 50m Medicare beneficiaries.”