Category Archives: management and leadership

HBR Blog: Social CEOs

https://hbr.org/2014/12/the-7-attributes-of-ceos-who-get-social-media/

The 7 Attributes of CEOs Who Get Social Media

Peter Aceto, the CEO of Tangerine, recently said in The Globe and Mail, “I would rather engage in a Twitter conversation with a single customer than see our company attempt to attract the attention of millions in a coveted Superbowl commercial.”

This is the preference of a truly social CEO. Unfortunately, chief executives that embrace and understand the promise of social media are rare, so rare that we call them “blue unicorns” in our book, A World Gone Social. Why blue unicorns? Because CEOs that embrace social as much as leaders like Aceto are still so uncommon that we aren’t just looking for any unicorn, we’re looking for a specific color of unicorn.

Five years ago, when boards were searching for a leader, social media competency wasn’t even on the radar. Now, according to the board members and CEOs we interviewed for our book, a strong social presence is often high on the list of factors they consider when vetting CEO candidates.

And five years from now? With the positive aspects of being a social CEOroutinely splashed across the business pages, social fluency will likely be on almost every board’s list of must-have leadership skills. Already, given a choice between similarly strong candidates — one with an impressive social presence, the other without – the choice is easy: boards increasingly prefer the modern leader.

According to recent research conducted by Domo, 30% of Fortune 500 CEOs have a presence on at least one social channel. And on paper, especially considering the Social Age is only six years old, 3 in 10 may not seem too bad a ratio. But even these so-called “social CEOs” aren’t that social.

A quick glance at their activity on LinkedIn, Facebook, or Twitter shows:

- The vast majority is using social media as a broadcast channel — a digital billboard to hawk their company’s products and services — not as a way to connect.

- For those who appear to be attempting to engage, their social activity feels impersonal and generic, as if a junior member of the marketing team is managing their social accounts and speaking for them. Of course, the CEOs who approach social in this manner are missing the point entirely.

So how do we know that a CEO is actually — personally — engaging on social media? What attributes do we recognize in truly social CEOs like Richard Branson, Pete Cashmore, Arianna Huffington and Peter Aceto? Here are the top seven traits we’ve observed over the five years we spent trend-watching and interviewing leaders:

- They Have an Insatiable Curiosity

Truly social CEOs are deeply curious. And that curiosity leads them to wonder, “What are people saying about our company? Our competitors? About their wants, needs, and aspirations that no one is fulfilling right now?” Many social CEOs are first drawn to social to listen. After all, there is no better way than social to collect real-time market intelligence, both through social monitoring and engaging followers.

- They Have a DIY Mindset

The same CEOs who look up information on Google rather than asking an assistant to do it are flocking to social. They don’t want to hear input from customers filtered through 13 layers of management. They don’t want to see a summary report on employee morale or customer satisfaction. They want their input raw and without any manipulation.

- They Have a “Bias for Action”

In 1982, we learned from Tom Peters and Robert Waterman in their book, In Search of Excellence, about how the best leaders had “a bias for action.” They live by a “ready, fire, aim” mentality and in the Social Age, this has never been more necessary – the 24/7 social conversation waits for no focus group or budget cycle. Sure, the marketing team supports their activity; they may even have a person dedicated to social monitoring of their accounts. But when the situation or sense of urgency dictates, they aren’t afraid of getting their hands dirty. Just watch truly social CEOs like Basecamp’s Jason Fried and Havas Media’s Paul Frampton: they’re often online, live, in the moment, and thus ready to respond and engage in real time.

- They Are Relentless Givers

Many social CEOs aren’t social just because they have a company to run; they see value in being social in every aspect of their lives. They care about more than the bottom line. They give back, they mentor, and they care about real social issues that have nothing to do with Twitter, Facebook and LinkedIn. We refer to those who act consistently in a collaborative, generous way as “relentless givers.” They constantly share what they know, connect others and — often for no other reason than because it is the right thing to do — they do good. One standout example isOCLC’s Skip Prichard, who blogs on leadership and shares insights from his favorite authors – often with no direct benefit to him or his organization.

- They Connect Instead of Promote

Want to spot an antisocial CEO? Read what they’re sharing on social media. Are they spreading the good word about their company while also interacting with others, from famous influencers to humble social newcomers? Or is their feed clearly a spigot of self-promotion? Are they answering questions from concerned stakeholders? Or are they only saying what investors want to hear? Social CEOs put down the digital megaphone and they build relationships.

- They’re the Company’s No. 1 Brand Ambassador

We have always looked to the boss as the face of the company. We admire the leaders whose brands, both personal and corporate, are led responsibly – and revile those whose company is seen as autocratic, self-serving and non-caring. As goes the personal brand of a CEO, so goes the brand. A study by Weber Shandwick backs up this observation: About two-thirds of customers say their perception of a CEO directly impacts their perception of the company. Social CEOs are building their personal brand whenever they engage on social media, and when they do it in an authentic and generous way, they’re also improving the company brand.

- They Lead with an OPEN Mindset

“OPEN” – short for Ordinary People, Extraordinary Network – means that no one person, even the highest-level leader, can have all the answers. Instead, we deliberately build personal relationships with those willing to help us discover the answers, together. Whether it’s managing a crisis, or rising up to meet an opportunity, a social CEO taps into her network’s combined expertise. Embracing the concept of OPEN is perhaps the purest indicator that a leader is truly social.

Writer Kare Anderson takes OPEN to the next level as she talks routinely of mutuality and deliberately becoming an opportunity maker. She said in herrecent TED talk, “Each one of us is better than anybody else at something… which disproves the popular notion that if you’re the smartest person in the room, you’re in the wrong room.”

No leader can afford to lead as they did in the Industrial Age. This is a new era with new rules. All around us, the entire world is flattening, democratizing, andsocializing. It’s quite possible that as the social age matures, there will be only two types of business leaders: social … and retired.

7 Emails You Need to Know How to Write

http://unreasonable.is/skills/the-7-emails-you-need-to-know-how-to-write/

The 7 Emails You Need to Know How to Write

Why Give a Damn:

Emails are how we communicate with each other in this day and age. Writing them well can be the difference between successfully building a relationship and not. This post includes example emails for how to get meetings, ask for introductions to investors, say no gracefully, and more!

The author of this post, Teju Ravilochan, is co-founder and CEO of the Unreasonable Institute.

When emailing, we do things that we’d never do in real life. Tweet This Quote

Emails are strangely awkward. They give us the ability to start a conversation with anyone in the world, without the social cues of an in-person interaction. So we do things that we’d never do in real life via email. Can you imagine walking up to someone at a dinner party, handing them a large document and saying, “Hey Steve, it’s great to meet you! I’ve heard a lot about you and was wondering if you’d give me feedback on my business plan?” And yet, I get emails like this. A lot of people get emails like this.

So this post is dedicated to effectively writing what I believe are seven of the most important relationship-building emails. I’ve assembled articles and examples for each of the emails below and hope this helps you to start the critical relationships you need to produce extraordinary results!

1. How to get busy people to respond to your emails.

Want to get in touch with Eric Schmidt, former CEO of Google? Adam Grant, New York Times best-selling author of Give and Take (which is one of my favorite business books of all time, by the way), lays out six key steps for getting important people to respond to your emails in this post. He includes a story of how a Princeton undergrad sent an email that got a response from then-Google CEO Eric Schmidt! This is a great post!

2. How to ask for an introduction.

This post from Scott Britton, whose company SinglePlatform, exited for $100 million, includes analysis of an email requesting an introduction. Critical elements include:

- An explicit ask

- A compelling context as to why you’re asking for the intro

- An example of traction or partnerships that boost credibility

- Appreciation, and

- A template email the recipient can forward onto the person you want an introduction to

Another Great Example: Tim Ferriss offers this exceptional example of how someone reached out to him asking for connections to angel investors.

3. How to make an introduction between two people.

LinkedIn Founder Reid Hoffman and two-time author and entrepreneur Ben Casnocha explain that there are three ways to introduce people over email. The very best of the three involves:

- Checking with both parties to make sure they want the introduction,

- Making the intro with a short explanation of who each person in the introduction is and why they should connect

- Clarifying who will take the next step (e.g. who will follow up first)

This might be more work than putting two people’s email addresses in the CC field and saying, “Jason and Brad, consider yourselves connected!” But it is far more effective in ensuring your true outcome: that the two people you are introducing meaningfully connect and build a mutually productive relationship.

Techstars Founder David Cohen receives 50 cold email requests for feedback each day. In the post above, he explains why the featured email brilliantly won his attention and earned thoughtful feedback from him. The core elements include:

- Knowing the person you’re emailing and showing them that (echoing Adam Grant’s post)

- Making the request specific and easy to answer for him

Read the post to see how it’s done concretely!

Scott Britton’s elements of a good meeting request include:

- Offering value to the recipient,

- Explaining the context of meeting clearly (ideally including a brief agenda),

- Asking for a small, discrete amount of time (like 25 minutes),

- Making it convenient for them (by offering to meet where it might be convenient for them), and

- Recognizing that they are giving you their time.

Are you noticing some patterns here? A little thoughtfulness goes a long way in getting people to say yes to your requests. Read the post to see an example!

6. How to be politely persistent in getting someone to write you back.

I assume that people I reach out to cold (and even people I get introduced to) won’t respond to my first email. It often takes 2-3 emails to hear back from them. Impact Hub Boulder Co-Founder Greg Berry taught me the best technique I’ve come across for getting responses for folks who haven’t emailed me back. It involves sending them an email about a week later saying,

The difference between successful people and very successful people is that very successful people say ‘no’ to almost everything. Tweet This Quote

I’ve written hundreds of these kinds of emails and received only one clearly negative response (which said, “Stop it. You’re annoying me”). Interestingly, that was the one email where I left out the phrase “friendly nudge” and didn’t ask them to “forgive me for emailing again.” But in other cases, I secured a funder for $1 million (which took several emails over the course of 6 months), and the New York Times best-selling author Chip Heath to serve as a mentor at Unreasonable Institute (which took over a fifteen emails over the course of four years).

7. How to say no gracefully.

In the words of Warren Buffet, “The difference between successful people and very successful people is that very successful people say ‘no’ to almost everything.” Odds are that tons of opportunities are flying your way: invitations to speak at conferences, requests for advice, suggestions to open operations in new locations. You might be excited by many of these, but when some come along that you’re not interested in, here are two examples of how to say no.

The first is a humorous example from author E.B. White, which I found in this blog post by Greg McKeown. It reads:

I must decline, for secret reasons.

Sincerely,

E.B. White”

The second example comes from an email I recently sent:

If there’s something quick I can help you with or if you have a specific question, do send me an email about it and I’ll be happy to get back to you!

My best,

Teju

Master these seven emailing skills and I submit that you will produce remarkable results for your work! Tweet This Quote

In Conclusion: Conclusion: Knowing how to make asks via email, particularly in being considerate to the people you are reaching out to, will go a long way in helping you build the relationships you’re looking to build. And the good news is that you can start practicing right away with everyone you email! If you would like, feel free to send me a practice email anytime at teju@unreasonableinstitute.org.

Happy emailing!

Don’t give reasons for prices – it triggers a psychological reflex to regain control and bargain down the price

http://www.forbes.com/sites/stevemeyer/2015/01/09/the-1-reason-why-salespeople-leave-money-on-the-table/

The No. 1 Reason Why Salespeople Leave Money On The Table

Salespeople talk too much.

In an earlier article, I discussed a study suggesting salespeople would be more persuasive if they relied more on visuals than words. Here we’ll talk about what’s perhaps the most likely point in the selling process where salespeople say too much – and trigger the price bully that lurks in every buyer’s heart.

Courting is a little like sales, right? Imagine you’re a guy who’s been dating a woman for some time and you decide to propose. You want to close the deal. So you buy her a ring and take her to a nice restaurant. As you hand her the ring, you lay out, like bullet points, the five reasons you’re the guy for her.

What she wants is for you to let the ring, and the sincerity expressed in your misty eyes, do the talking. Laying out your value proposition at this point seems like desperation, or doubt. She’s thinking, “After all that courting, why does he think he needs to convince me? Or is he not convinced himself?”

How many times have you seen salespeople, just before a close, try to justify their price by revisiting the key benefits of their product or service? How many times have you succumbed to that urge yourself?

It’s a bad selling tactic. The research suggests you will trigger the same reaction in your prospect that our hapless Romeo triggered in his Juliet.

Justifying your price seems like common sense. If you’re going to ask someone to do something, how could it be a bad idea to remind them of the reasons? There’s actually a landmark study out there that seems to give credence to the idea. Unfortunately, most people completely misread its conclusions.

The study, called “The Mindlessness of Ostensibly Thoughtful Action,” was conducted in 1978. It observed how people waiting in line to use a copier responded when somebody at the back of the line tried to cut ahead. When the person simply asked to go first, 60% agreed. When the person said, “May I use the Xerox machine because I have to make a copy?” 93% said yes – even though the “reason” itself made no sense.

Based on this study, salespeople are often advised that there’s some mechanism in the human psyche that responds to reasons, and that enumerating them will improve close rates.

Problem is, there was a second part to that study. In Part 2 the researchers raised the stakes. They had the line-cutter say, for example, “I need to make 20 copies; can I go first?” Predictably, fewer people said yes, only 24%. When the line-cutter tried again, adding a bogus reason why he had to make 20 copies, the reason had no effect.

So that study showed that reasons work when the stakes are low but provide no benefit when they’re high, which they usually are in selling situations.

A more recent study showed that giving reasons not only doesn’t help, it actually hurts salespeople. Researchers analyzed two negotiations over the price of an apartment. With buyer Group 1, the sellers presented a price, then added justifications, pointing out that the building had an elevator and was in a desirable neighborhood. With buyer Group 2, they simply named the price and remained silent.

Buyer Group 2 didn’t bargain as hard and agreed to a higher price. Why? The researchers said the justifications made buyers in Group 1 feel they were being pushed into a corner, and that the seller was trying to do their thinking for them. And here’s what’s really interesting: The Group 1 buyers responded to justifications by coming up with reasons why the apartment wasn’t so great. “Yeah, that’s all true, but parking is a pain and there aren’t enough washing machines.”

The researchers described this pushback as a psychological reflex to regain control, which is the most powerful insight in this study. Justifications are perceived by the buyer as an attempt to take control. Just stating your price and remaining silent leaves the buyer in control. For whatever reason, buyers who feel they’re in control are less likely to undermine your value proposition and demand a lower price.

All that said, there is of course an appropriate time to lay out your value proposition – early in your discussions as you’re conducting discovery and mapping your product or service to customer needs. Just don’t do it late in the sales cycle when you’re negotiating price.

As hard as it may seem, you’ll get a higher price if you just say, “Here’s what it costs,” and then shut up.

You might want to go easy on the misty eyes though.

Coca-Cola’s internal comms management

http://www.linkedin.com/pulse/20141007162311-30084557-the-new-way-we-need-to-schedule-meetings?_mSplash=1&trk=api*a171147*s179395*

The Genius Way Coca-Cola Employees Manage Their Email, Plus More Tips

At least that’s how Snapchat’s Emily White and Coca Cola’s Wendy Clark said they approach time management in a hyper-connected world. And the idea of unplugging? Ha.

“Rather than the choice to consciously disconnect, there’s much more of a trend of choosing who to connect with and in what context,” White said. “It’s very much about conversations.”

During a panel at Fortune’s Most Powerful Women Summit on Monday, White, the COO of Snapchat and a veteran of Instagram, Facebook and Google, said she now relies on her phone more than her computer to get work done. “You’re not just getting information and solving problems; you’re getting to communicate in motion like never before,” White said. “This is the reason I can have kids and still have a relationship with them, and work in the evenings when I get home [after the kids are in bed].”

For Clark, the president of sparkling brands and strategic marketing for Coca-Cola North America, being present at work or with her family is the key to living in an over-connected world. “The thing people want most from you is your focus and attention,” Clark said. “You destroy that when you think that you’re multitasking because you’re not accomplishing either.”

That means no phones at the dinner table, for her or her kids. And if she’s expecting an urgent email from the CEO when they’re putt-putt golfing, she’s found the best thing to do is tell them that mommy needs to go respond to an email for 10 minutes and hope they don’t screw up her score while she’s gone.

So when you’re constantly connected, how do you get anything done?

- Make the most of your subject lines. Clark said that at Coca-Cola, employees include tags in their subject lines to help manage email flow: URGENT, ACTION REQUIRED and INFORM.

- Form habits you can keep. Recognize that you’re setting the standard for what people in your life will do, White said. If you start emailing people at night, people will expect you to be on email at night.

- Give yourself white space during the day. Clark’s a fan of Google’s “speedy” meeting invitations, which are constrained to 50 minutes, without an option to override the system. By changing the standard for meetings to 25 or 50 minutes, the remaining five or 10 minutes can be used to check email or go to the bathroom, allowing everyone to be more present when they’re together.

- Set boundaries. Camille Preston, author of Rewired, says having boundaries will help you with willpower. Put fences up to focus on what you want to do at that time.

- Don’t hit send. If you want to work on the weekends, save your emails as drafts, but don’t actually send them until Monday unless they’re urgent. As a leader, you need to let people enjoy their weekends.

For more coverage of Fortune’s Most Powerful Women Summit, go here.

To continue the conversation about issues that are relevant to professional women, visit Connect: Professional Women’s Network.

10 Predicaments Facing a New CEO

http://www.iedp.com/Blog/Ten-Predicaments-Facing-a-New-CEO

|

||

10 Predicaments Facing a New CEO |

||

|

Finally the day arrived, when Peter was appointed as the CEO of the multinational technology giant. After months of speculation, apprehension and expectation; all came to a logical conclusion and everyone sighed with relief. Stakeholders were satisfied, the board were confident of having made the right choice, and the outgoing CEO felt that he was leaving the company in safe hands. When a week long ceremony and celebrations were over, Peter got some reflective moments to himself. That night, he could not sleep. He wondered, ‘what next’? Where does he go now, from here onward? Who to look up to, where to escalate and where does the buck stop now? Unfortunately, the buck now stops with him. Peter knew that from now onwards, everybody including customers, stakeholders, employees, the market and board will look to him for direction; looking for those ‘Pearls of Wisdom’ that he had been craving to apply or holding on to reveal now that he had reached this stage. This a usual scenario in most companies, where succession has happened or is likely to happen in the near future. CEOs are always in the ‘Hot Seat’, irrespective of whether their businesses are struggling due to competition, context or capability; or doing exceptionally but where the continual drive for aspirational growth continues. They have to deal with a number of predicaments that put a strain on their time, energy and decision making. Either way, here are 10 top dilemmas new CEOs will do well to know in advance and brace their organizations to deal with effectively:

Finding business coherence amidst the randomness of internal and external events is a perpetual dilemma for the CEOs. A lot will depend upon, how he marshals his resources in new and innovative ways to discover that elusive growth orbit for which he has been appointed as the CEO. Discovering new ways of value creation and building conviction around them will help him deal with above predicaments, effectively. Each and every dilemma must be dealt with a filter of Staying Relevant – Proactive Disruption and Building case for Strategic Change. Finally, not everyone will understand the path undertaken by CEO but as long as these paths enable him and the company ‘Stay Relevant’ to its customers, they must be pursued with conviction. Illustration: King Arthur. Fresco (detail) in the Corridor, Trinci Palace, Foligno, Italy Further Information

|

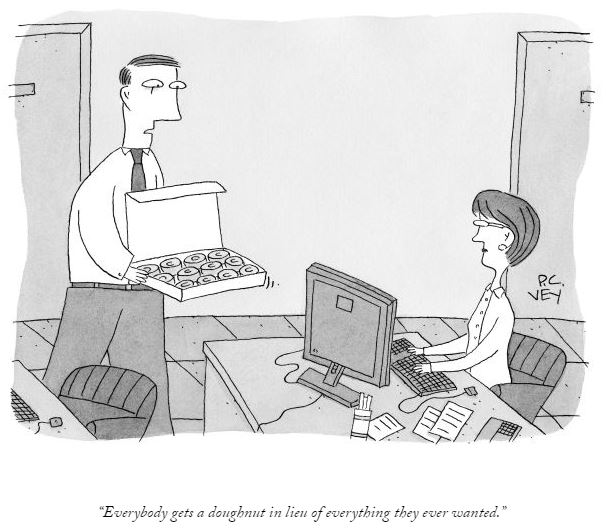

Everybody gets a doughnut in lieu of everything they’ve ever wanted

Artificial intelligence meets the C-suite

Artificial intelligence meets the C-suite

http://www.mckinsey.com/Insights/Strategy/Artificial_intelligence_meets_the_C-suite

Jeremy Howard: Today, machine-learning algorithms are actually as good as or better than humans at many things that we think of as being uniquely human capabilities. People whose job is to take boxes of legal documents and figure out which ones are discoverable— that job is rapidly disappearing because computers are much faster and better than people at it.

In 2012, a team of four expert pathologists looked through thousands of breast-cancer screening images, and identified the areas of what’s called mitosis, the areas which were the most active parts of a tumor. It takes four pathologists to do that because any two only agree with each other 50 percent of the time. It’s that hard to look at these images; there’s so much complexity. So they then took this kind of consensus of experts and fed those breast-cancer images with those tags to a machine-learning algorithm. The algorithm came back with something that agreed with the pathologists 60 percent of the time, so it is more accurate at identifying the very thing that these pathologists were trained for years to do. And this machine-learning algorithm was built by people with no background in life sciences at all. These are total domain newbies

Artificial intelligence meets the C-suite

Technology is getting smarter, faster. Are you? Experts including the authors of The Second Machine Age, Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee, examine the impact that “thinking” machines may have on top-management roles.

September 2014

The matter is more than academic. Many of the jobs that had once seemed the sole province of humans—including those of pathologists, petroleum geologists, and law clerks—are now being performed by computers.

And so it must be asked: can software substitute for the responsibilities of senior managers in their roles at the top of today’s biggest corporations? In some activities, particularly when it comes to finding answers to problems, software already surpasses even the best managers. Knowing whether to assert your own expertise or to step out of the way is fast becoming a critical executive skill.

Video

Managing in the era of brilliant machines: An interview

In this interview with McKinsey’s Rik Kirkland, Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee explain the organizational challenge posed by the Second Machine Age.

Yet senior managers are far from obsolete. As machine learning progresses at a rapid pace, top executives will be called on to create the innovative new organizational forms needed to crowdsource the far-flung human talent that’s coming online around the globe. Those executives will have to emphasize their creative abilities, their leadership skills, and their strategic thinking.

To sort out the exponential advance of deep-learning algorithms and what it means for managerial science, McKinsey’s Rik Kirkland conducted a series of interviews in January at the World Economic Forum’s annual meeting in Davos. Among those interviewed were two leading business academics—Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee, coauthors of The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies (W. W. Norton, January 2014)—and two leading entrepreneurs: Anthony Goldbloom, the founder and CEO of Kaggle (the San Francisco start-up that’s crowdsourcing predictive-analysis contests to help companies and researchers gain insights from big data); and data scientist Jeremy Howard. This edited transcript captures and combines highlights from those conversations.

The Second Machine Age

What is it and why does it matter?

Andrew McAfee: The Industrial Revolution was when humans overcame the limitations of our muscle power. We’re now in the early stages of doing the same thing to our mental capacity—infinitely multiplying it by virtue of digital technologies. There are two discontinuous changes that will stick in historians’ minds. The first is the development of artificial intelligence, and the kinds of things we’ve seen so far are the warm-up act for what’s to come. The second big deal is the global interconnection of the world’s population, billions of people who are not only becoming consumers but also joining the global pool of innovative talent.

Erik Brynjolfsson: The First Machine Age was about power systems and the ability to move large amounts of mass. The Second Machine Age is much more about automating and augmenting mental power and cognitive work. Humans were largely complements for the machines of the First Machine Age. In the Second Machine Age, it’s not so clear whether humans will be complements or machines will largely substitute for humans; we see examples of both. That potentially has some very different effects on employment, on incomes, on wages, and on the types of companies that are going to be successful.

Video

Putting artificial intelligence to work: An interview with Anthony Goldbloom and Jeremy Howard

Machine-learning experts Anthony Goldbloom and Jeremy Howard tell McKinsey’s Rik Kirkland how smart machines will impact employment.

Jeremy Howard: Today, machine-learning algorithms are actually as good as or better than humans at many things that we think of as being uniquely human capabilities. People whose job is to take boxes of legal documents and figure out which ones are discoverable— that job is rapidly disappearing because computers are much faster and better than people at it.

In 2012, a team of four expert pathologists looked through thousands of breast-cancer screening images, and identified the areas of what’s called mitosis, the areas which were the most active parts of a tumor. It takes four pathologists to do that because any two only agree with each other 50 percent of the time. It’s that hard to look at these images; there’s so much complexity. So they then took this kind of consensus of experts and fed those breast-cancer images with those tags to a machine-learning algorithm. The algorithm came back with something that agreed with the pathologists 60 percent of the time, so it is more accurate at identifying the very thing that these pathologists were trained for years to do. And this machine-learning algorithm was built by people with no background in life sciences at all. These are total domain newbies.

Andrew McAfee: We thought we knew, after a few decades of experience with computers and information technology, the comparative advantages of human and digital labor. But just in the past few years, we have seen astonishing progress. A digital brain can now drive a car down a street and not hit anything or hurt anyone—that’s a high-stakes exercise in pattern matching involving lots of different kinds of data and a constantly changing environment.

Why now?

Computers have been around for more than 50 years. Why is machine learning suddenly so important?

Erik Brynjolfsson: It’s been said that the greatest failing of the human mind is the inability to understand the exponential function. Daniela Rus—the chair of the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Lab at MIT—thinks that, if anything, our projections about how rapidly machine learning will become mainstream are too pessimistic. It’ll happen even faster. And that’s the way it works with exponential trends: they’re slower than we expect, then they catch us off guard and soar ahead.

Andrew McAfee: There’s a passage from a Hemingway novel about a man going broke in two ways: “gradually and then suddenly.” And that characterizes the progress of digital technologies. It was really slow and gradual and then, boom—suddenly, it’s right now.

Jeremy Howard: The difference here is each thing builds on each other thing. The data and the computational capability are increasing exponentially, and the more data you give these deep-learning networks and the more computational capability you give them, the better the result becomes because the results of previous machine-learning exercises can be fed back into the algorithms. That means each layer becomes a foundation for the next layer of machine learning, and the whole thing scales in a multiplicative way every year. There’s no reason to believe that has a limit.

Erik Brynjolfsson: With the foundational layers we now have in place, you can take a prior innovation and augment it to create something new. This is very different from the common idea that innovations get used up like low-hanging fruit. Now each innovation actually adds to our stock of building blocks and allows us to do new things.

One of my students, for example, built an app on Facebook. It took him about three weeks to build, and within a few months the app had reached 1.3 million users. He was able to do that with no particularly special skills and no company infrastructure, because he was building it on top of an existing platform, Facebook, which of course is built on the web, which is built on the Internet. Each of the prior innovations provided building blocks for new innovations. I think it’s no accident that so many of today’s innovators are younger than innovators were a generation ago; it’s so much easier to build on things that are preexisting.

Jeremy Howard: I think people are massively underestimating the impact, on both their organizations and on society, of the combination of data plus modern analytical techniques. The reason for that is very clear: these techniques are growing exponentially in capability, and the human brain just can’t conceive of that.

There is no organization that shouldn’t be thinking about leveraging these approaches, because either you do—in which case you’ll probably surpass the competition—or somebody else will. And by the time the competition has learned to leverage data really effectively, it’s probably going to be too late for you to try to catch up. Your competitors will be on the exponential path, and you’ll still be on that linear path.

Let me give you an example. Google announced last month that it had just completed mapping the exact location of every business, every household, and every street number in the entirety of France. You’d think it would have needed to send a team of 100 people out to each suburb and district to go around with a GPS and that the whole thing would take maybe a year, right? In fact, it took Google one hour.

Now, how did the company do that? Rather than programming a computer yourself to do something, with machine learning you give it some examples and it kind of figures out the rest. So Google took its street-view database—hundreds of millions of images—and had somebody manually go through a few hundred and circle the street numbers in them. Then Google fed that to a machine-learning algorithm and said, “You figure out what’s unique about those circled things, find them in the other 100 million images, and then read the numbers that you find.” That’s what took one hour. So when you switch from a traditional to a machine-learning way of doing things, you increase productivity and scalability by so many orders of magnitude that the nature of the challenges your organization faces totally changes.

The senior-executive role

How will top managers go about their day-to-day jobs?

Andrew McAfee: The First Machine Age really led to the art and science and practice of management—to management as a discipline. As we expanded these big organizations, factories, and railways, we had to create organizations to oversee that very complicated infrastructure. We had to invent what management was.

In the Second Machine Age, there are going to be equally big changes to the art of running an organization.

I can’t think of a corner of the business world (or a discipline within it) that is immune to the astonishing technological progress we’re seeing. That clearly includes being at the top of a large global enterprise.

I don’t think this means that everything those leaders do right now becomes irrelevant. I’ve still never seen a piece of technology that could negotiate effectively. Or motivate and lead a team. Or figure out what’s going on in a rich social situation or what motivates people and how you get them to move in the direction you want.

These are human abilities. They’re going to stick around. But if the people currently running large enterprises think there’s nothing about the technology revolution that’s going to affect them, I think they would be naïve.

So the role of a senior manager in a deeply data-driven world is going to shift. I think the job is going to be to figure out, “Where do I actually add value and where should I get out of the way and go where the data take me?” That’s going to mean a very deep rethinking of the idea of the managerial “gut,” or intuition.

It’s striking how little data you need before you would want to switch over and start being data driven instead of intuition driven. Right now, there are a lot of leaders of organizations who say, “Of course I’m data driven. I take the data and I use that as an input to my final decision-making process.” But there’s a lot of research showing that, in general, this leads to a worse outcome than if you rely purely on the data. Now, there are a ton of wrinkles here. But on average, if you second-guess what the data tell you, you tend to have worse results. And it’s very painful—especially for experienced, successful people—to walk away quickly from the idea that there’s something inherently magical or unsurpassable about our particular intuition.

Jeremy Howard: Top executives get where they are because they are really, really good at what they do. And these executives trust the people around them because they are also good at what they do and because of their domain expertise. Unfortunately, this now saddles executives with a real difficulty, which is how to become data driven when your entire culture is built, by definition, on domain expertise. Everybody who is a domain expert, everybody who is running an organization or serves on a senior-executive team, really believes in their capability and for good reason—it got them there. But in a sense, you are suffering from survivor bias, right?

You got there because you’re successful, and you’re successful because you got there. You are going to underestimate, fundamentally, the importance of data. The only way to understand data is to look at these data-driven companies like Facebook and Netflix and Amazon and Google and say, “OK, you know, I can see that’s a different way of running an organization.” It is certainly not the case that domain expertise is suddenly redundant. But data expertise is at least as important and will become exponentially more important. So this is the trick. Data will tell you what’s really going on, whereas domain expertise will always bias you toward the status quo, and that makes it very hard to keep up with these disruptions.

Erik Brynjolfsson: Pablo Picasso once made a great observation. He said, “Computers are useless. They can only give you answers.” I think he was half right. It’s true they give you answers—but that’s not useless; that has some value. What he was stressing was the importance of being able to ask the right questions, and that skill is going to be very important going forward and will require not just technical skills but also some domain knowledge of what your customers are demanding, even if they don’t know it. This combination of technical skills and domain knowledge is the sweet spot going forward.

Anthony Goldbloom: Two pieces are required to be able to do a really good job in solving a machine-learning problem. The first is somebody who knows what problem to solve and can identify the data sets that might be useful in solving it. Once you get to that point, the best thing you can possibly do is to get rid of the domain expert who comes with preconceptions about what are the interesting correlations or relationships in the data and to bring in somebody who’s really good at drawing signals out of data.

The oil-and-gas industry, for instance, has incredibly rich data sources. As they’re drilling, a lot of their drill bits have sensors that follow the drill bit. And somewhere between every 2 and 15 inches, they’re collecting data on the rock that the drill bit is passing through. They also have seismic data, where they shoot sound waves down into the rock and, based on the time it takes for those sound waves to be captured by a recorder, they can get a sense for what’s under the earth. Now these are incredibly rich and complex data sets and, at the moment, they’ve been mostly manually interpreted. And when you manually interpret what comes off a sensor on a drill bit or a seismic survey, you miss a lot of the richness that a machine-learning algorithm can pick up.

Andrew McAfee: The better you get at doing lots of iterations and lots of experimentation—each perhaps pretty small, each perhaps pretty low-risk and incremental—the more it all adds up over time. But the pilot programs in big enterprises seem to be very precisely engineered never to fail—and to demonstrate the brilliance of the person who had the idea in the first place.

That makes for very shaky edifices, even though they’re designed to not fall apart. By contrast, when you look at what truly innovative companies are doing, they’re asking, “How do I falsify my hypothesis? How do I bang on this idea really hard and actually see if it’s any good?” When you look at a lot of the brilliant web companies, they do hundreds or thousands of experiments a day. It’s easy because they’ve got this test platform called the website. And they can do subtle changes and watch them add up over time.

So one of the implications of the manifested brilliance of the crowd applies to that ancient head-scratcher in economics: what the boundary of the firm should be. What should I be doing myself versus what should I be outsourcing? And, now, what should I be crowdsourcing?

Implications for talent and hiring

It’s important to make sure that the organization has the right skills.

Jeremy Howard: Here’s how Google does HR. It has a unit called the human performance analytics group, which takes data about the performance of all of its employees and what interview questions were they asked, where was their office, how was that part of the organization’s structure, and so forth. Then it runs data analytics to figure out what interview methods work best and what career paths are the most successful.

Anthony Goldbloom: One huge limitation that we see with traditional Fortune 500 companies—and maybe this seems like a facile example, but I think it’s more profound than it seems at first glance—is that they have very rigid pay scales.

And they’re competing with Google, which is willing to pay $5 million a year to somebody who’s really great at building algorithms. The more rigid pay scales at traditional companies don’t allow them to do that, and that’s irrational because the return on investment on a $5 million, incredibly capable data scientist is huge. The traditional Fortune 500 companies are always saying they can’t hire anyone. Well, one reason is they’re not willing to pay what a great data scientist can be paid elsewhere. Not that it’s just about money; the best data scientists are also motivated by interesting problems and, probably most important, by the idea of working with other brilliant people.

Machine learning and computers aren’t terribly good at creative thinking, so the idea that the rewards of most jobs and people will be based on their ability to think creatively is probably right.

Gloria Steinem: The Truth Will Set You Free, But first it will piss you off

Adyashanti on Enlightenment

Enlightenment is a destructive process. It has nothing to do with becoming better or being happier. Enlightenment is the crumbling away of untruth. It’s seeing through the facade of pretence. It’s the complete eradicatin of everything we imagined to be true. Adyashanti

Enlightenment is a destructive process. It has nothing to do with becoming better or being happier. Enlightenment is the crumbling away of untruth. It’s seeing through the facade of pretence. It’s the complete eradicatin of everything we imagined to be true. Adyashanti

VIEWPOINT: No career move is more profound than the step up to CEO.

VIEWPOINT: No career move is more profound than the step up to CEO.

Himanshu Saxena is a thinker, writer and speaker on concepts such as Big Picture, Reimagination, Strategy & Innovation and Leadership@Top Level. He is currently enabling TCS BPS in aligning strategy, coaching and developing leaders of tomorrow.

Himanshu Saxena is a thinker, writer and speaker on concepts such as Big Picture, Reimagination, Strategy & Innovation and Leadership@Top Level. He is currently enabling TCS BPS in aligning strategy, coaching and developing leaders of tomorrow. Vijay Govindarajan is the Coxe Distinguished Professor at the Tuck School at Dartmouth and the author of NYT and WSJ Best Seller, Reverse Innovation.

Vijay Govindarajan is the Coxe Distinguished Professor at the Tuck School at Dartmouth and the author of NYT and WSJ Best Seller, Reverse Innovation.