Category Archives: cool

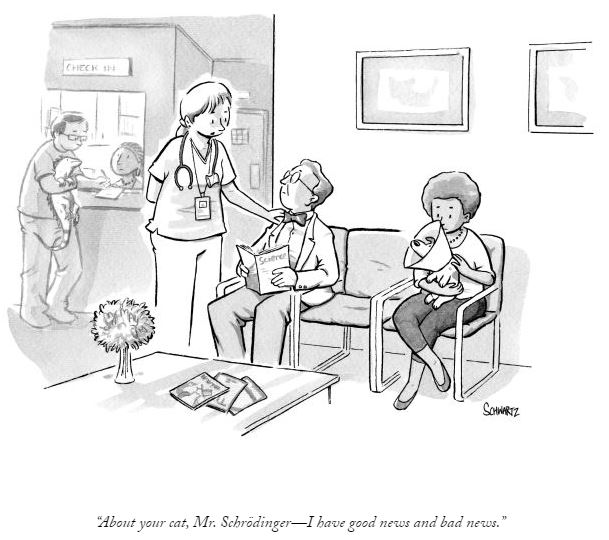

New Yorker: Schrodinger’s Vet

Yeats: Education is not the filling of a pail, but the lighting of a fire

Peter Hinssen: The Tiger and The Rock

EDxBrussels – Peter Hinssen – The TIGER & the ROCK

Why Extrapolating WON’T WORK & What it means for HEALTH http://www.tedxbrussels.eu About TEDx, x = independently organized event In the spirit of ideas worth…

http://wn.com/tedxbrussels_-_peter_hinssen_-_the_tiger_&_the_rock

8:20 – The Contiguous United States – macdonald’s proximity to people in the US

9:10 The Flip: Pharma moving to Health as a Service (no longer a product)

Institutions > Communities (trust)

Reactive > Proactive (attitude)

http://www.datapointed.net/visualizations/maps/distance-to-nearest-mcdonalds-sept-2010/

Okham’s Razor – Limits to Growth – Kerryn Higgs

“The conscience and intelligent manipulation of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism constitute an invisible government that represents the true ruling power of our country. It is they who pull the wires that control the public mind.” Edward Bernaise (Sigmund Freud’s Cousin, Founder of modern PR)

http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/ockhamsrazor/limits-to-growth/6088808

Limits to growth

Australian writer Dr Kerryn Higgs has written a book called Collision Course – Endless Growth On A Finite Planet, in which she examines how society’s commitment to growth has marginalized scientific findings on the limit of growth, calling them bogus predictions of imminent doom.

Transcript

Robyn Williams: Growth or no growth? You may have heard Dick Smith on Breakfasta couple of weeks ago saying that unlimited growth is impossible and we must do something else. But what? There is, of course, a way of improving what we do more efficiently and stopping waste. Peter Newman from Perth gave an example on Late Night Live late last year: If we used trains instead of trucks for freight, it would halve the costs and save many, many lives. We don’t do it because we always do what we’ve always done. Kerryn Higgs, who’s with the University of Tasmania, has just brought out a book called Collision Course – Endless Growth on a Finite Planet, published by MIT Press and she has recently been appointed a Fellow of the International Centre of the Club of Rome.

Kerryn Higgs: I came across The Limits to Growth quite by accident in 1972, just when it was published. It was commissioned by the Club of Rome and written by a team of researchers at MIT, led by Donella and Dennis Meadows. The book changed the way I thought about Nature, people, history, everything. It persuaded me that physics matters, and that the idea of ever-expanding economic growth is a delusion. Up to then, I was a mainstream humanities person, history being my main discipline, and writing my passion. I did grow up in the countryside and loved the natural world, but I had no real intuition of an impending environmental crisis. And here was this little book suggesting that if we carried on with our exponential expansion, our system would collapse at some point in the middle of the 21st century.

Although galloping economic growth already seemed normal to most younger people living in the developed world in 1972, the growth that took off after WW2 was not normal. It is absolutely unprecedented in all of history. Nothing like it has ever occurred before: large and rapidly growing populations, accelerating industrialisation, expanding production of every kind. All new. The Meadows team found that we could avoid collapse if we slowed down the physical expansion of the economy. But this would mean two very difficult changes— slowing human population growth and slowing the entire cycle of physical production from material extraction through to the disposal of waste. The book was persuasive to me and I expected its message to have an impact on human affairs. But as the years rolled by, it seemed there was very little—and then, even less. In fact, I gradually became aware that most people thought “the Club of Rome got it wrong” and scorned the book as an ignorant tract from “doomsters”, an especially common view among economists. I want to point out, though, that recent research from Melbourne University’s Graham Turner, shows that the Meadows team did not get it wrong. Their projections for what would happen if we carried on business as usual tally almost exactly with what has actually occurred in the 40 years since 1972.

But while scientists from Rachel Carson onwards sounded alarm about numerous problems associated with growth, this was not the case in our governments, bureaucracies, and in public debate, where economic growth was gradually being entrenched as the central objective of collective human effort. This really puzzled me.

How come the Club of Rome got such a terrible press?

How did scientists lose credibility? When I was young, science was almost a god. A few decades later, scientists were being flippantly brushed aside.

How did economists displace scientists as the crucial policy advisors and the architects of public debate, setting the criteria for policy decisions?

How did economic growth become accepted as the only solution to virtually all social problems—unemployment, debt and even the environmental damage growth was causing?

And how did ever-increasing income and consumption become the meaning of life, at least for us in the rich world? It was not the meaning of life when I was young.

Answering these questions took me back through human history. A few developments were especially decisive.

Around 1900, the modern corporation emerged. Over just a decade or two, many of the current transnationals came into being in the US (with names like Coca Cola, Alcoa and DuPont). International Harvester amalgamated 85% of US farm machinery into one corporation in just a few years. Adam Smith’s free enterprise economy was being transformed into something very different. A process of perpetual consolidation followed and by now, frighteningly few corporations control the majority of world trade and revenue, giving them colossal power. The new corporations of the early 20thcentury banded together into industry associations and business councils like the immensely influential US Chamber of Commerce, which was formed out of local chambers from across the country in 1912. These organisations exploited the newly emerging Public Relations industry, launching a barrage of private enterprise propaganda, uninterrupted for more than a century, and still very healthy today. Peabody coal, for example, recently signed up one of the world’s PR giants, Burson-Marsteller, for a PR campaign to convince leaders that coal is the solution to poverty.

Back in 1910 universal suffrage threatened the customary dominance of the business classes, and PR was an excellent solution. If workers were going to vote, they’d need the right advice. No-one expressed it better than Edward Bernays, Freud’s nephew, who is credited with founding the PR industry. Bernays was candid:

The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the… masses is an important element in democratic society (he wrote). Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism … constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country… It is they who pull the wires which control the public mind.

PR became an essential tool for business to consolidate its power right through the century, culminating in the 1970s project to “litter the world with free market think tanks”. By 2013, there were nearly 7,000 of these, all over the world; the vast majority were conservative, free market advocates, many on the libertarian fringe, and financed by big business. They cultivate a studied appearance of independence, though one think tank vice-president came clean. “There is no such thing as a disinterested think tanker,” he said. “Somebody always builds the tank, and it’s usually not Santa Claus or the Tooth Fairy.” Funding think tanks is always about “shaping and reshaping the climate of public opinion”.

Nonetheless, the claim to independence has been so successful that most think tanks have tax-free charity status and their staff constantly feature in the media as if they were independent and peer-reviewed experts.

Another decisive development was the “bigger pie” strategy. Straight after World War 2, governments took on a new role of fostering growth. The emphasis increasingly fell on baking a bigger pie, so the slices could get bigger but the pie would not have to be divided up any more equitably. Growth could function as an alternative to fairness. Thorny problems like world poverty were designated growth problems and leaders in the decolonising world often embraced a growth-oriented version of development, a version that rarely helped their poor majorities. Growth allowed the privileged to maintain and even extend their opulence, while professing to be saving the world from poverty. It’s frequently claimed that growth is lifting millions out of poverty. But, apart from China, this is not really the case. China has indeed decreased the numbers of its extreme poor, though this has been achieved with disastrous environmental decline and increasing inequality.

Meanwhile, progress is patchy elsewhere. After 70 years of economic growth, with the world economy now 8 to 10 times bigger than it was in 1950, there are still 2 and a half billion people living on less than $2 a day, more than a third of the people on earth, and about the same number as in 1981. Growth has not been shared. Underlying the popularity of growth, there’s a great clash of values between mainstream economics and the physical sciences.

Economists see the human economy as the primary system—odd when you consider that the planet’s been here for about 4.6 billion years, and life for something like 3.8 billion. The human era is less than a whisker on this timescale, but for economists Nature is just the extractive sector of their primary system, the economy. For scientists and ecological economists, the primary system is the planet – and it’s self-evidently finite. The human economy with its immense material extraction and vast waste, exists entirely within the earth system. Self-evident as these boundaries might seem, they remain invisible or contested in mainstream economics and are of little concern to politicians or citizens in most countries. Hardly a news bulletin goes by without stories of growth expected, growth threatened, or growth achieved. Growth is the watchword of both major parties here and around the world and remains the accepted solution to poverty, pollution and debt.

And yet, however necessary growth is to our current economic arrangements, and however desirable from the point of view of our expectations of material well-being and comfort, it’s hardly a practical aim if it’s based on a misperception of reality.

While we assume that a high and increasing level of material consumption is normal and desirable, we ignore the peculiarity of our times and the encroaching threats to us and our planet.

We are well into dangerous territory in three areas:

Firstly, species are going extinct 100 to 1000 times faster than the background rate.

Secondly, the nitrogen cycle is completely disrupted. In nature, nitrogen is largely inert in our atmosphere. Today, mainly through making fertiliser, nitrogen is flooding through our rivers, groundwater and continental shelves, fuelling algal blooms that lead to dead zones and fish kills.

And thirdly we are on the way to a very hot planet. Unless we change rapidly in the extremely near future, we risk an increase of 4 degrees Centigrade by 2100. So far, an increase of less than 1 degree is melting the West Antarctic icesheet, glaciers nearly everywhere and even the massive Greenland icecap.

Meanwhile, the rate of carbon dioxide and methane emissions continues to rise. In fact, right through the decade it took to write my book, I was staggered as these emissions defied all protocols and agreements, and rose faster and faster every year, setting a new record in 2013. Four degrees may be a bridge too far, and yet our culture is cheerfully crossing it.

I started out as a student of human history and ended up studying the intersection between human history and natural history. Humans have had local effects for thousands of years but on a global scale, the collision is new. Humans were a flea on the face of the earth for most of our history andit’s probably true to say this is the very first time one species—ours—has taken over the entire planetary system for its own sole use. In human-focused terms, this may seem perfectly reasonable. In planetary terms, it’s weird and completely impractical.

While our best agricultural land, last remnants of white box woodland and the Great Barrier Reef are put at risk for the extraction of gas and coal, which we should aim to stop burning anyway if we want a liveable world, it seems that only citizen revolt is left to counter it.

Let’s hope we succeed.

The ground of our being is at stake.

Robyn Williams: Kerryn Higgs. She’s with the University of Tasmania and her book, published by MIT Press, is called Collision Course – Endless Growth on a Finite Planet.Kerryn has recently been appointed a Fellow of the International Centre of the Club of Rome. Next week I shall introduce the proud Professor who’s just moved into that crumpled brown paper bag designed by Frank Gehry for the University of Technology, Sydney: Roy Green on innovation in Australia and what’s not right.

Guests

- Dr Kerryn Higgs

- Writer

University Associate

University of Tasmania

Fellow of the International Centre of the Club of Rome

Publications

- Title

- Collision Course – Endless Growth On A Finite Planet

- Author

- Kerryn Higgs

- Publisher

- MIT Press

Credits

- Presenter

- Robyn Williams

- Producer

- Brigitte Seega

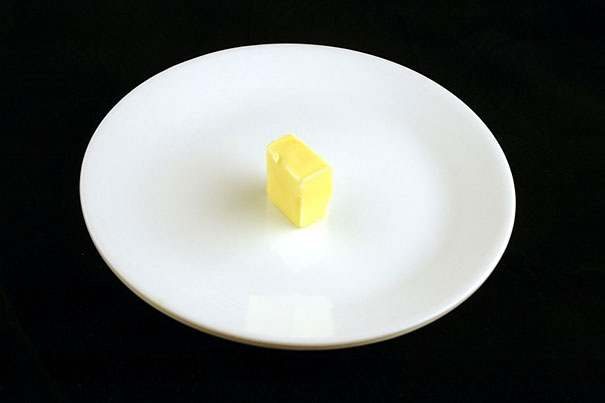

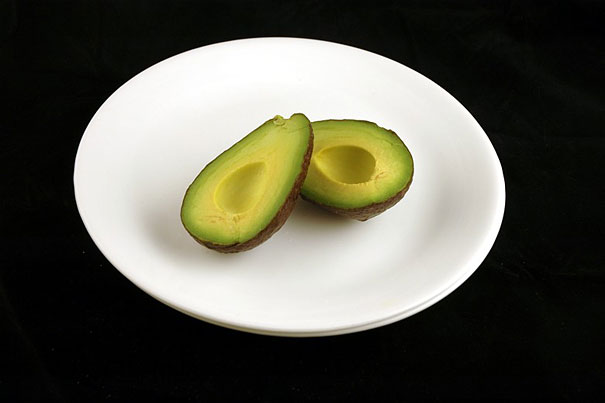

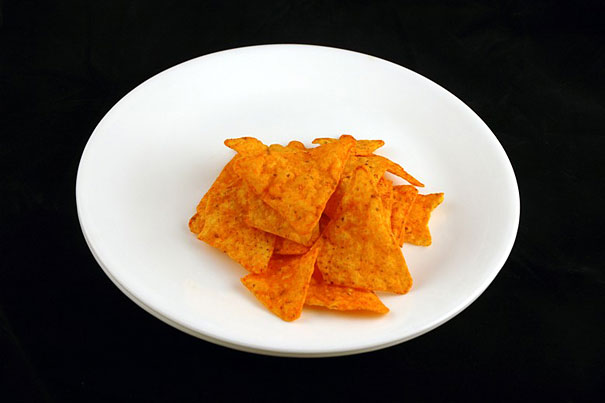

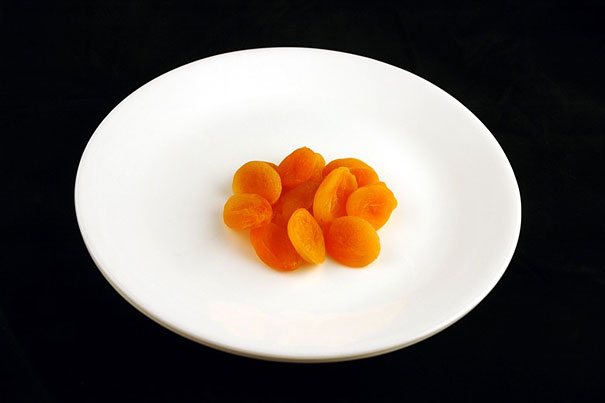

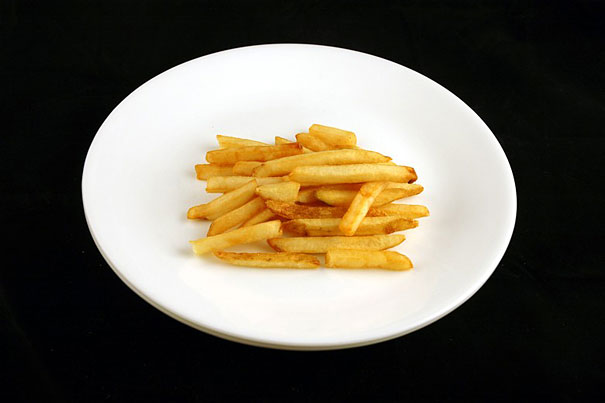

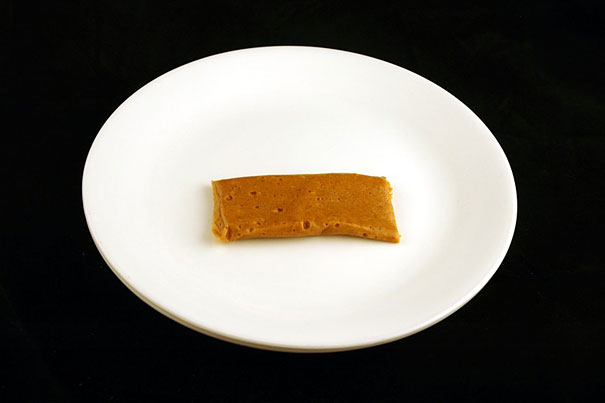

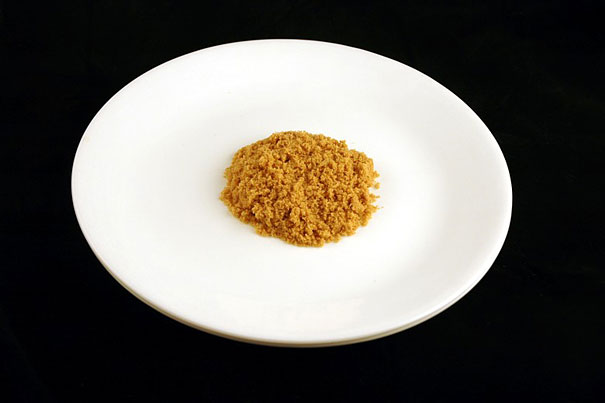

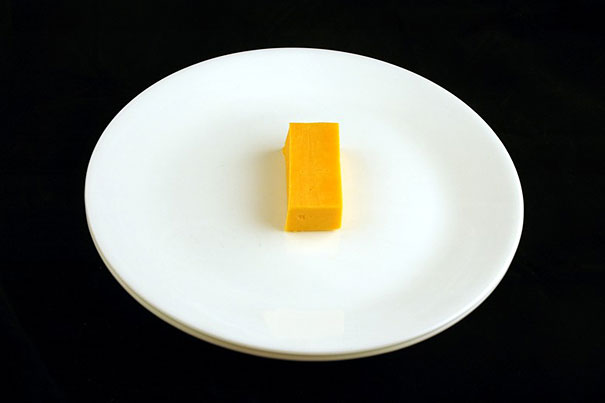

What 200 Calories Look Like In Different Foods

What 200 Calories Look Like In Different Foods

940K views

Apples (385 grams / 13.5 oz)

Butter (28 grams / 0.98 oz)

Broccoli (588 grams / 20.7 oz)

Snickers Chocolate Bar (41 grams / 1.45 oz)

Cooked Pasta (145 grams / 5.11 oz)

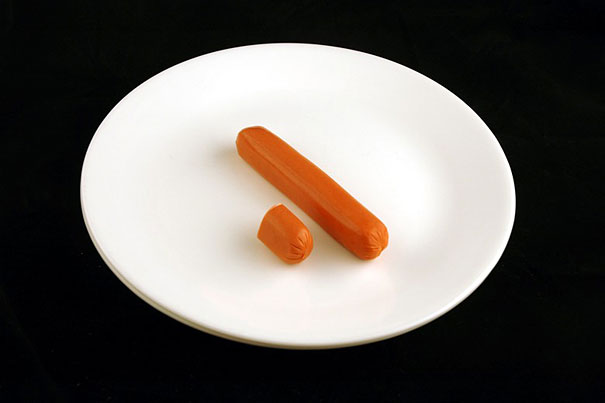

Hot Dogs (66 grams / 2.33 oz)

Kiwi Fruit (328 grams / 11.6 oz)

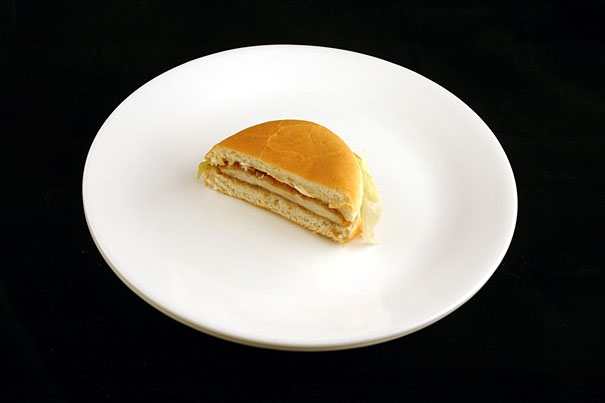

Jack in the Box Cheeseburger (75 grams / 2.6 oz)

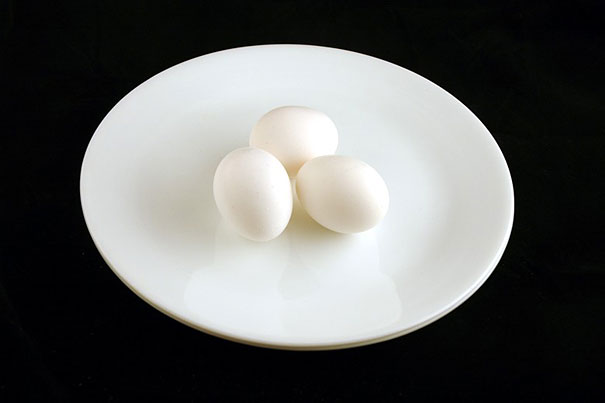

Eggs (150 grams / 5.3 oz)

Celery (1425 grams / 50.3 oz)

Blackberry Pie (56 grams / 1.97 oz)

Mini Peppers (740 grams / 26.1 oz)

Canned Black Beans (186 grams / 6.56 oz)

Werther’s Originals Candy (50 grams / 1.76 oz)

Jack in the Box Chicken Sandwich (72 grams / 2.5 oz)

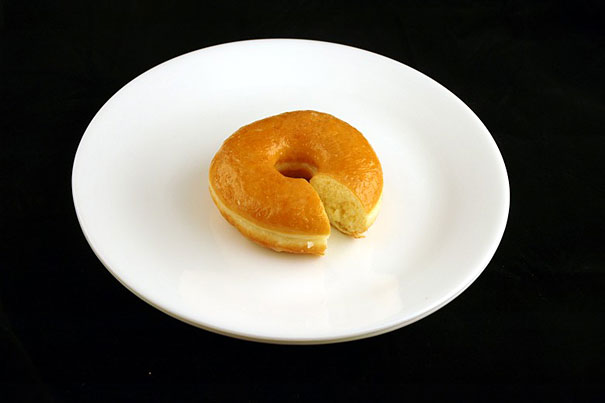

Glazed Doughnut (52 grams / 1.8 oz)

French Sandwich Roll (72 grams / 2.5 oz)

Avocado (125 grams / 4.4 oz)

Canned Sweet Corn (308 grams / 10.9 oz)

Baby Carrots (570 gram / 20.1 oz)

Canned Green Peas (357 grams / 12.6 oz)

Canned Pork and Beans (186 grams / 6.56 oz)

Doritos (41 grams / 1.44 oz)

Dried Apricots (83 grams / 2.9 oz)

Jack in the Box French Fries (73 grams / 2.6 oz)

Fried Bacon (34 grams / 1.2 oz)

Fruit Loops Cereal (51 grams / 1.8 oz)

Grapes (290 grams / 10.2 oz)

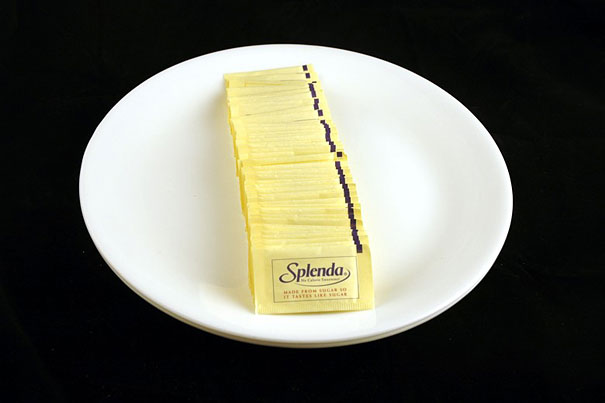

Splenda Artifical Sweetener (50 grams / 1.8 oz)

Gummy Bears (51 grams / 1.8 oz)

Hershey Kisses (36 grams / 1.27 oz)

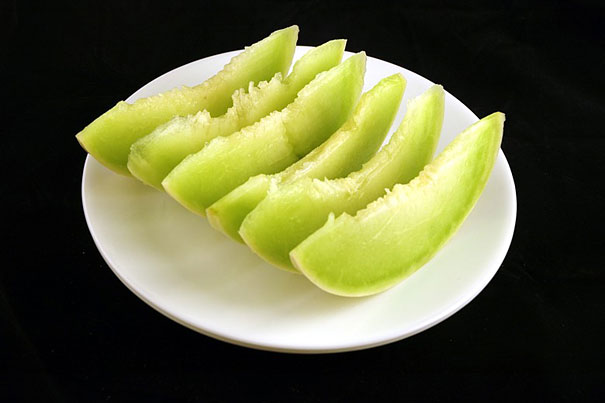

Honeydew Melon (553 grams / 19.5 oz)

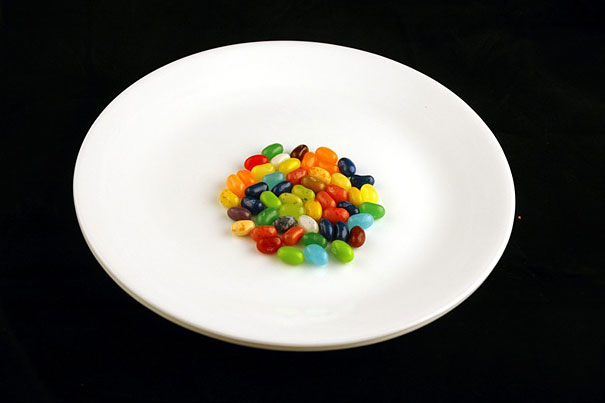

Jelly Belly Jelly Beans (54 grams / 1.9 oz)

Ketchup (226 grams / 7.97 oz)

M&M Candy (40 grams / 1.4 oz)

Red Onions (475 grams / 16.75 oz)

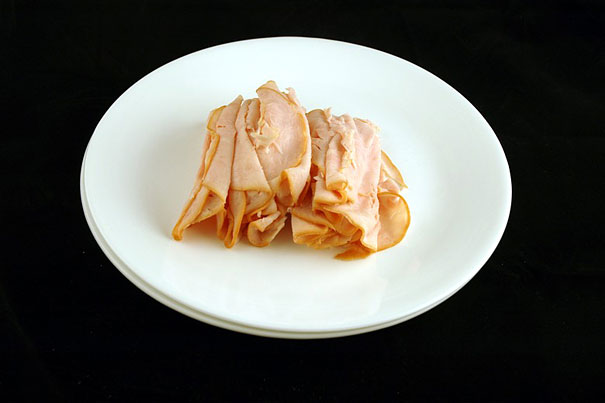

Sliced Smoked Turkey (204 grams / 7.2 oz)

Coca Cola (496 ml / 16.77 oz)

Canola Oil (23 grams / 0.8 oz)

Smarties Candy (57 grams / 2 oz)

Tootsie Pops (68 grams / 2.4 oz)

Whole Milk (333 ml / 11.3 fl oz)

Balsamic Vinegar (200 ml / 6.8 fl oz)

Lowfat Strawberry Yogurt (196 grams / 6.9 oz)

Canned Chili con Carne (189 grams / 6.7 oz)

Canned Tuna Packed in Oil (102 grams / 3.6 oz)

Fiber One Cereal (100 grams / 3.5 oz)

Flax Bread (90 grams / 3.17 oz)

Blueberry Muffin (72 grams / 2.5 oz)

Bailey’s Irish Cream (60 ml / 2.02 fl oz)

Cranberry Vanilla Crunch Cereal (55 grams / 1.9 oz)

Cornmeal (55 grams / 1.94 oz)

Wheat Flour (55 grams / 1.94 oz)

Peanut Butter Power Bar (54 grams / 1.9 oz)

Puffed Rice Cereal (54 grams / 1.9 oz)

Puffed Wheat Cereal (53 grams / 1.87 oz)

Brown Sugar (53 grams / 1.87 oz)

Salted Pretzels (52 grams / 1.83 oz)

Medium Cheddar Cheese (51 grams / 1.8 oz)

Potato Chips (37 grams / 1.3oz)

Sliced and Toasted Almonds (35 grams / 1.23 oz)

Peanut Butter (34 grams / 1.2 oz)

Salted Mixed Nuts (33 grams / 1.16 oz)

Establishing markets in prevention and wellness – 3 examples

1. AIA Vitality Life Insurance

- https://www.aiavitality.com.au/vmp-au/

- Wendy Brown – University of Queensland wbrown@hms.uq.edu.au

- Tracy Kolbe-Alexander – University of Queensland

2. Data Driven Healthcare Quality Markets

3. Abu Dhabi Health Authority – Weqaya

Vitality Institute Commission – Recommendation 3 http://thevitalityinstitute.org/commission/create-markets-for-health/

“Discipline makes daring possible” Atul Gawande – Century of the System – Reith Lectures

Pyrmont vacant lots to be sold off for charity

PDF: Wakil family property sell-off_ $200m raised for charitable foundation

http://www.smh.com.au/nsw/wakil-family-property-selloff-200m-raised-for-charitable-foundation-20141212-125bq7.html

Wakil family property sell-off: $200m raised for charitable foundation

The Wakils sold the Griffiths Teas building in Surry Hills for $22 million last month. Photo: Steven Siewert

The Wakils, owners of many of Sydney’s mysterious derelict buildings in Pyrmont and the CBD, have begun selling off their vast property portfolio with plans to set up a major charitable foundation.

The off-market sell-off has already raised $200 million with more properties, some vacant since the 1970s, under negotiation.

In a city where housing is at a premium and areas such as Pyrmont have become rapidly gentrified, the Wakil’s decision to sit on their property portfolio was controversial and provided many a squatter’s opportunity.

“Scariest eviction ever”: The vacant and overgrown Terminus Hotel in Pyrmont. Photo: Steven Siewert

“Scariest eviction ever”: The vacant and overgrown Terminus Hotel in Pyrmont. Photo: Steven Siewert

The elderly couple had once planned to restore the portfolio of historic buildings they own. But according to Karbon Properties agent, Joshua Watts, who has handled some of the sales, the renovations “became beyond them” and Isaac and Susan Wakil, now in their late 80s, have opted to give back to Sydney in another way.

The purpose of the foundation they are planning has not yet been made clear.

The Wakils have no children and the only known relative is a nephew.

Old advertising signs still on display at the derelict Terminus Hotel. Photo: Steven Siewert

Old advertising signs still on display at the derelict Terminus Hotel. Photo: Steven Siewert

The famous Griffiths Tea Warehouse, in Wentworth Avenue, Surry Hills, sold in November for $22 million to Cornerstone Property group. Its new owner plans to turn the iconic Sydney landmark into New York style apartments.The nearby Key College building, sold for an undisclosed sum to a group of investors including Michael Teplitsky, who has plans for a boutique hotel development. A vast warehouse and vacant lot at 100 Harris Street, Pyrmont near the Star Casino has sold for over $90 million.

Other famous mouldering landmarks, such as the Terminus Hotel, also in Harris Street, once owned by the father of a bikie killed in the Milperra bikie massacre, and empty for more than 30 years, are under negotiation. The pub still displays its original beer posters and is covered with vines that have snaked through the brickwork.

A vast bond store covered in ferns and moss, also within a stone’s throw of the casino, is on the market too.

Susan and Isaac Wakil at a gala night at the Opera House.

Susan and Isaac Wakil at a gala night at the Opera House.

The Wakils made their money in the garment trade and were once patrons of the arts and the opera in Sydney.

Mrs Wakil who was born in the then Romanian province of Bessarabia in 1932, told the Herald in 1961 she still remembered her father being dragged to a Siberian gulag for being a capitalist land owner when she was seven.

After imprisonment in a Soviet concentration camp, her mother died and the young Susan and her aunt escaped to Australia. Her father migrated here after his release. Mr Wakil was born in Baghdad in Iraq.

The Wakil property portfolio.

The Wakil property portfolio.

In the 1970s and 1980s the Wakils, like many successful migrants, began investing in property. They favoured stone buildings and big old brick warehouses in then unfashionable parts of the city, like Pyrmont and the fringes of the CBD near Central. In Pyrmont alone, they have more than 10 properties.

But unlike most property developers, the Wakils didn’t renovate, sell, or even rent them out, even though they displayed “For Lease” signs, sometimes with numbers so old they did not include the 9 that Sydney numbers have had for 20 years.

The only building which was tenanted was 100 Harris Street, Pyrmont, where the Wakils had the office of their company. In the 1990s and early 2000s the Wakils’ cream Rolls-Royce could be seen most days parked in the driveway of Citilease. But in recent years the Wakils have seldom ventured from their Vaucluse home.

Susan Wakil at the Randwick races.

Susan Wakil at the Randwick races.

In a city where housing is at a premium and areas such as Pyrmont have rapidly gentrified, the Wakil’s decision to just sit on their property portfolio was controversial.

Local Pyrmont business owners told of their frustration at being unable to rent some of the most prominent sites, and instead having to watch them deteriorate.

The Herald reported in 2000 that squatters also met their match. Mickie Quick, a co-founder of the squatter’s group Squatspace told how his group taken up digs in the Terminus Hotel. “We got inside once and changed the locks but we only lasted a few weeks. It was one of the scariest evictions I had ever had. Two hired guns came in with sledgehammers in the night.”

What Makes Gladwell Fascinating

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/20131007120010-69244073-what-makes-malcolm-gladwell-fascinating

What Makes Malcolm Gladwell Fascinating

Suddenly, everyone wanted to talk about Malcolm Gladwell’s ideas, and I felt right at home. He made social science cool in watercooler chatter, spawning an entire genre of books that blend stories and studies to explain how the world works. He carried me through a decade of dinner parties with Blink and Outliers. With last week’s release of David and Goliath, I’ll be set for a while.

Gladwell refers to his books as “conversation starters,” and when people pick up that conversation, they often start criticizing his work. As a social scientist, I think this is a missed opportunity. I’m not saying that Gladwell’s writing is perfect or that his arguments are always true. I just want to make sure that we don’t throw out the baby with the bathwater, since we can learn as much from analyzing what he does right as from poking holes in his work. At a recent event, the discussion shifted away from the substance of Gladwell’s arguments, and toward the style: why is he arguably the most spellbinding nonfiction writer of our time?

The most popular explanation was storytelling skills: he’s a master of suspense, to the point that his books read like mystery novels. Some people waxed poetic about how he brings characters to life—who could forget the Six Degrees of Lois Weisberg or the tragic genius of Chris Langan? Others highlighted his ability to present sticky concepts that quickly make their way into the lexicon, like thin slicing, the 10,000 hour rule of expertise, and the magic number of 150 for social groups. And of course, his ability to illustrate social science with examples from popular culture loomed large in the discussion. Who wouldn’t want to read about how Hush Puppies took off, why Phantom of the Opera and Sesame Street hit it big, and what led Bill Gates and the Beatles to greatness? (There’s even a Malcolm Gladwell Book Generator website that plays on this notion by proposing new titles like Clarissa: How One Woman Explained It All; The Cheers Effect: How and Why Everybody Knows Your Name; and Lando: Intergalactic Lessons in Smoothness.)

The most popular explanation was storytelling skills: he’s a master of suspense, to the point that his books read like mystery novels. Some people waxed poetic about how he brings characters to life—who could forget the Six Degrees of Lois Weisberg or the tragic genius of Chris Langan? Others highlighted his ability to present sticky concepts that quickly make their way into the lexicon, like thin slicing, the 10,000 hour rule of expertise, and the magic number of 150 for social groups. And of course, his ability to illustrate social science with examples from popular culture loomed large in the discussion. Who wouldn’t want to read about how Hush Puppies took off, why Phantom of the Opera and Sesame Street hit it big, and what led Bill Gates and the Beatles to greatness? (There’s even a Malcolm Gladwell Book Generator website that plays on this notion by proposing new titles like Clarissa: How One Woman Explained It All; The Cheers Effect: How and Why Everybody Knows Your Name; and Lando: Intergalactic Lessons in Smoothness.)

If you believe that Gladwell’s success is primarily driven by his writing, I think you’ve overlooked the most important factor. What makes him most interesting is not the narratives themselves, but rather the ideas behind them.

In 1971, a sociologist named Murray Davis published a groundbreaking paper that opened with these two lines:

It has long been thought that a theorist is considered great because his theories are true, but this is false. A theorist is considered great, not because his theories are true, but because they are interesting.”

Davis argued that the difference between the dull and the interesting lies in the element of surprise. When an idea affirms what we already believe, we’re bored—we call it obvious. But when an idea is counterintuitive, we’re intrigued. Our curiosity is piqued, and we’re motivated to ask questions: how could this be? Is it really true? What else might this explain?

Challenging our assumptions is what Malcolm Gladwell does best. To see how he does it, let’s take a look at what Davis called The Index of the Interesting. Davis classified 12 different ways of challenging conventional wisdom, and Gladwell’s key ideas map beautifully onto at least five of them.

1. Bad is Good and Good is Bad

The idea here is to take a negative and unveil its positive side, or vice-versa. This is the theme of David and Goliath, where Gladwell argues that disadvantages can give us advantages. Who would have thought that a disability like dyslexia could actually make people more successful? With reasoning reminiscent of the Daredevil comic books, he illustrates how the absence of one ability—reading—can lead people to develop other abilities in areas like creative problem solving, acting, listening, and rule-bending. He presents data suggesting that losing a parent as a child, one of the worst things that can happen in life, may actually increase your odds of becoming president or prime minister. He also explores the other side of the coin, arguing that power led the British Army and Southern segregationists to underestimate uprisings in Northern Ireland and Alabama.

2. What Looks Like an Individual Phenomenon is Really a Collective Phenomenon

Another way to challenge assumptions is to show that what we think is caused by individuals is in fact caused by broader societal forces. This is the heart of Outliers. Gladwell argues that we think professional hockey and soccer players make it because of talent and hard work, but it’s really about being born a few months earlier than their peers. We assume that planes crash due to mistakes made by individual pilots, but it’s actually about the cultures in which they were raised. We believe Bill Gates and the Beatles achieved greatness because of their talents, but they had to be in the right place at the right time.

Gladwell does the opposite in The Tipping Point, arguing that major collective changes are actually fueled by small numbers of people. Styles and social movements catch on when connectors build bridges between people and ideas, mavens share expertise, and salesmen convince people to come aboard.

3. What Seems to Succeed Fails, and What Seems to Fail Succeeds

It’s interesting when something that appears to work doesn’t, or when something that looks ineffective proves to be effective. In David and Goliath, Gladwell covers evidence that contrary to popular belief, small classes in schools don’t lead children to learn more. In Blink, he adopts the reverse strategy, showing that although we expect reason to outdo intuition, we underestimate the power of intuition. We believe that the best way to spot fake art is through systematic analysis, but an expert can tell in the blink of an eye. Even when critical information is stripped away, and we only have tiny clues, our intuition can be strikingly accurate. A 10-second silent video clip is enough to spot an engaging teacher; an audiotape with the words garbled so that we can only hear the tone still allows us to identify the surgeon who was sued for malpractice; and a 15-minute conversation about taking out the garbage allows us to predict which marriages will fail.

4. What Appears To Be Local is Global

It’s also surprising when seemingly isolated events are in fact driven by common forces. This is another hallmark of The Tipping Point, which shows how the same kinds of dynamics can explain the spread of sexually transmitted diseases, pop culture trends, and crime sprees. We also see it in David and Goliath, where the willingness of underdogs to play by a different set of rules serves as a lens for illuminating events as diverse as the success of the American civil rights movement and an inferior basketball team with an inexperienced coach making the national championship. (The Gladwell Book Generator picks up on this theme too, with the faux title Nothing: What Sandcastles Can Teach Us About North Korean Economic Policy.)

5. What Looks Like Disorder is Actually Order

The ability to find structure in chaos is another quality of interesting theories, and this is a signature strength of The Tipping Point. We think fads come out of nowhere, but if we appreciate Gladwell’s three rules of epidemics—the law of the few, the stickiness factor, and the power of context—we can better understand the systematic factors that cause them to spread. Confusion also turns into clarity inOutliers, where the puzzle of why a man with genius IQ works as a bouncer is traced to his difficult upbringing, and in David and Goliath, where the mystery of the greatest medical breakthroughs in modern history is also informed by a difficult upbringing.

On Becoming Interesting

Of course, execution is important. Before presenting an idea, Davis observed that the author “articulates the taken-for-granted assumptions” of the audience, and only then reveals how the idea challenges these assumptions. This rhetorical strategy is visible in each Gladwell book: articulate what we currently think, and then present examples and evidence to show how our beliefs are incomplete, inadequate, inconsistent, or just plain wrong.

Interesting ideas are counterintuitive, but not all counterintuitive ideas are interesting. Davis warned that if we believe too strongly in an idea, we don’t want to see it questioned:

one must be careful not to go too far. There is a fine but definite line between asserting the surprising and asserting the shocking, between the interesting and the absurd… those who attempt to deny the strongly held assumptions of their audience will have their very sanity called into question. They will be accused of being lunatics; if scientists, they will be called ’crackpots’. If the difference between the inspired and the insane is only in the degree of tenacity of the particular audience assumptions they choose to attack, it is perhaps for this reason that genius has always been considered close to madness.”

Gladwell is very careful on this front. In David and Goliath, he intentionally avoided analyzing the Israel-Palestine conflict, knowing that it was a hot-button issue, and instead chose other conflicts that were more likely to intrigue than offend. At the same time, recognizing that his ideas need to have meaningful consequences, he addresses topics that matter to society. Gladwell writes about improving education and fighting crime, making planes safer and curing cancer, electing the right president and championing human rights. He also writes about ideas that matter to us as individuals. As Davis put it:

an audience will find a theory to be interesting only when it denies the significance of some part of their present ’on-going practical activity’… and insists that they should be engaged in some new on-going practical activity instead. If this practical consequence of a theory is not immediately apparent to its audience, they will respond to it by rejecting its value until someone can concretely demonstrate its utility: ’So what?’ ’Who cares?’ ‘Why bother?’ ’What good is it?’”

Gladwell’s books make us care. He challenges us to rethink how we raise our children, how we build our workplaces, and how we live our lives. He gives us hope that if we practice enough, we can become great musicians or athletes. That if an idea is worthwhile, we can make it take off. That if we change the way we evaluate people, we can overcome stereotypes and give disadvantaged people an equal chance. That if we face disadvantages of our own, we can draw strength from them.

The Dangers of Interestingness

Although it’s tempting to use the Index of the Interesting as a guide for developing an idea, Davis advised us not to do that. It works better as a mirror than a map. When we try to generate ideas in this formulaic fashion, it comes at the expense of creativity. Rather, the Index comes in handy once we have an idea: we can use it to explore different assumptions that we might be challenging. But this too proves difficult, Davis observed, because “assumptions about a topic” are often “too diverse or too amorphous” for any idea to be “universally interesting.” Perhaps Gladwell’s true genius lies here, in identifying common assumptions that lie just beneath the surface—beliefs that are so widely accepted, so taken for granted, that we don’t even know we believe in them.

The punch line from Davis is that interestingness is in the eye of the beholder. What’s fascinating to one audience is obvious to another. Over time, assumptions evolve, and reactions depend on the current assumptions of your audience. This means that if you successfully champion an interesting idea, it will eventually cease to be interesting, because everyone will believe it. And that’s why we need Malcolm Gladwell to keep writing new books.

Adam is a Wharton professor, an organizational psychologist, and the author of Give and Take: A Revolutionary Approach to Success, a New York Times and Wall Street Journal bestseller. Follow him here by clicking the yellow FOLLOW above and on Twitter @AdamMGrant

Photo: Pop!Tech/Flickr

I used to dread going to parties. I stood around struggling with small talk, waiting for an opening to debate about big ideas. That changed 13 years ago, the day I read

I used to dread going to parties. I stood around struggling with small talk, waiting for an opening to debate about big ideas. That changed 13 years ago, the day I read

Comments (3)

Add your comment

Peter Strachan :

12 Feb 2015 6:57:48pm

Thanks Kerryn for outlining the problem and much of its genesis. I find it interesting and frustrating that the obvious solution to our predicament is not mentioned.

If we have a citizens revolt, and I believe that we will eventually come to that, what direction would this revolt take society? Call me old fashioned but I was rather hoping that human intellect could come to a better solution than amorphous revolt against the status quo.

As we look around at existing resource constrained parts of our planet, there are already many visions of that citizens revolt already underway. In the Middle East, in North Africa, Rwanda, in eastern Europe and recently even on our doorstep in The Solomon Islands overpopulation, lack of water and unequal distribution of wealth has led to civil unrest and war, often cloaked in ethnic or religious garb to disguise its true cause.

The solution is already in our hands and its called family planning or contraception if you like.

It is clear that humanity will not be able to avert expansion of societal collapse which has already shown its early phase, while its population numbers keep rising by 80 million pa. Yet there is an unmet desire by women and men to plan and reduce fertility rates. Why are we not providing free choice to those who want this? Why do we continue to promote high birthrates?

Within a decade, population growth rates could be significantly reduced and begin a necessary decline towards a more sustainable level.

But who, apart from Kelvin Thompson is leading the charge? Perhaps more people should know of www.populationparty.org.au?

Reply Alert moderator

Stephen S :

14 Feb 2015 9:43:10am

Gillard and Burke made sure that Labor’s 2011 ‘Sustainable Population Strategy’ contained little factual information and studiously avoided all these pressing questions.

For another generation I fear, the opportunity was lost for a serious national debate about Australia’s rigid postwar policy of sustained high population growth.

Reply Alert moderator

Michael Lardelli :

14 Feb 2015 3:05:22pm

An interesting talk Kerryn. As to the “why” of the current obsession with economic growth, the fault is in us. While, as individuals, we pretend to rationality, humans, as a group, do not act in this way. As the products of evolution by natural selection, we act to maximise reproduction – and pity the person who tries to argue against that! For males, greater wealth gives us more access to females. For females, greater wealth gives higher social status and more probable survival of children.

The fact is that we NEED to believe in economic growth because, without that, we are forced to face up to the falsity of what I call “The Big Lie” – namely that we can all improve our lives / get rich. I wrote an essay on this a few years ago:

http://www.onlineopinion.com.au/view.asp?article=13487&page=0

When people are young they can be idealistic and believe that they can change the world. But that would require that the world be a rational place.

When people are older and more cynical like me they realise that human irrationality is a surging tide against which nothing can stand. It will wash over the world and then retreat. All radically new biological innovations thrown up by Nature are like this. Just like a newly evolved microorganism sweeps through a host population wreaking destruction until it – and the host – evolve to commensality, so the new and incredibly adaptable human species will do the same, although how many thousands of years that will take is unknown.

In the meantime, those of us who understand the inevitability of this process can find some small amount of solace by attempting to change things in our local community to enhance the survival of our own children, friends, neighbours and communities. At the local level, the rational part of one human can sometimes make a difference. And there is no sense in getting depressed about the inevitable.