As a 23-year-old math genius one year out of Harvard, Jeff Hammerbacher arrived at Facebook when the company was still in its infancy. This was in April 2006, and Mark Zuckerberg gave Hammerbacher—one of Facebook’s first 100 employees—the lofty title of research scientist and put him to work analyzing how people used the social networking service. Specifically, he was given the assignment of uncovering why Facebook took off at some universities and flopped at others. The company also wanted to track differences in behavior between high-school-age kids and older, drunker college students. “I was there to answer these high-level questions, and they really didn’t have any tools to do that yet,” he says.

Over the next two years, Hammerbacher assembled a team to build a new class of analytical technology. His crew gathered huge volumes of data, pored over it, and learned much about people’s relationships, tendencies, and desires. Facebook has since turned these insights into precision advertising, the foundation of its business. It offers companies access to a captive pool of people who have effectively volunteered to have their actions monitored like so many lab rats. The hope—as signified by Facebook’s value, now at $65 billion according to research firm Nyppex—is that more data translate into better ads and higher sales.

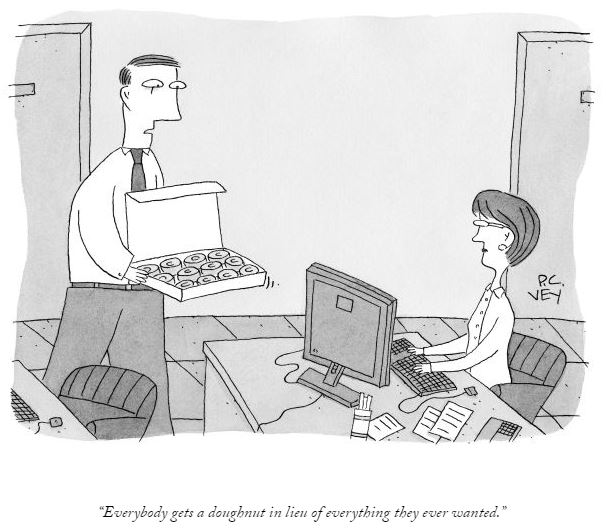

After a couple years at Facebook, Hammerbacher grew restless. He figured that much of the groundbreaking computer science had been done. Something else gnawed at him. Hammerbacher looked around Silicon Valley at companies like his own, Google (GOOG), and Twitter, and saw his peers wasting their talents. “The best minds of my generation are thinking about how to make people click ads,” he says. “That sucks.”

You might say Hammerbacher is a conscientious objector to the ad-based business model and marketing-driven culture that now permeates tech. Online ads have been around since the dawn of the Web, but only in recent years have they become the rapturous life dream of Silicon Valley. Arriving on the heels of Facebook have been blockbusters such as the game maker Zynga and coupon peddler Groupon. These companies have engaged in a frenetic, costly war to hire the best executives and engineers they can find. Investors have joined in, throwing money at the Web stars and sending valuations into the stratosphere. Inevitably, copycats have arrived, and investors are pushing and shoving to get in early on that action, too. Once again, 11 years after the dot-com-era peak of the Nasdaq, Silicon Valley is reaching the saturation point with business plans that hinge on crossed fingers as much as anything else. “We are certainly in another bubble,” says Matthew Cowan, co-founder of the tech investment firm Bridgescale Partners. “And it’s being driven by social media and consumer-oriented applications.”

There’s always someone out there crying bubble, it seems; the trick is figuring out when it’s easy money—and when it’s a shell game. Some bubbles actually do some good, even if they don’t end happily. In the 1980s, the rise of Microsoft (MSFT), Compaq (HPQ), and Intel (INTC) pushed personal computers into millions of businesses and homes—and the stocks of those companies soared. Tech stumbled in the late 1980s, and the Valley was left with lots of cheap microprocessors and theories on what to do with them. The dot-com boom was built on infatuation with anything Web-related. Then the correction began in early 2000, eventually vaporizing about $6 trillion in shareholder value. But that cycle, too, left behind an Internet infrastructure that has come to benefit businesses and consumers.

This time, the hype centers on more precise ways to sell. At Zynga, they’re mastering the art of coaxing game players to take surveys and snatch up credit-card deals. Elsewhere, engineers burn the midnight oil making sure that a shoe ad follows a consumer from Web site to Web site until the person finally cracks and buys some new kicks.

This latest craze reflects a natural evolution. A focus on what economists call general-purpose technology—steam power, the Internet router—has given way to interest in consumer products such as iPhones and streaming movies. “Any generation of smart people will be drawn to where the money is, and right now it’s the ad generation,” says Steve Perlman, a Silicon Valley entrepreneur who once sold WebTV to Microsoft for $425 million and is now running OnLive, an online video game service. “There is a goodness to it in that people are building on the underpinnings laid by other people.”

So if this tech bubble is about getting shoppers to buy, what’s left if and when it pops? Perlman grows agitated when asked that question. Hands waving and voice rising, he says that venture capitalists have become consumed with finding overnight sensations. They’ve pulled away from funding risky projects that create more of those general-purpose technologies—inventions that lay the foundation for more invention. “Facebook is not the kind of technology that will stop us from having dropped cell phone calls, and neither is Groupon or any of these advertising things,” he says. “We need them. O.K., great. But they are building on top of old technology, and at some point you exhaust the fuel of the underpinnings.”

And if that fuel of innovation is exhausted? “My fear is that Silicon Valley has become more like Hollywood,” says Glenn Kelman, chief executive officer of online real estate brokerage Redfin, who has been a software executive for 20 years. “An entertainment-oriented, hit-driven business that doesn’t fundamentally increase American competitiveness.”

Hammerbacher quit Facebook in 2008, took some time off, and then co-founded Cloudera, a data-analysis software startup. He’s 28 now and speaks with the classic Silicon Valley blend of preternatural self-assurance and save-the-worldism, especially when he gets going on tech’s hottest properties. “If instead of pointing their incredible infrastructure at making people click on ads,” he likes to ask, “they pointed it at great unsolved problems in science, how would the world be different today?” And yet, other than the fact that he bailed from a sweet, pre-IPO gig at the hottest ad-driven tech company of them all, Hammerbacher typifies the new breed of Silicon Valley advertising whiz kid. He’s not really a programmer or an engineer; he’s mostly just really, really good at math.

Hammerbacher grew up in Indiana and Michigan, the son of a General Motors (GM) assembly-line worker. As a teenager, he perfected his curve ball to the point that college scouts from the University of Michigan and Harvard fought for his services. “I was either going to be a baseball player, a poet, or a mathematician,” he says. Hammerbacher went with math and Harvard. Unlike one of his more prominent Harvard acquaintances—Facebook co-founder Mark Zuckerberg—Hammerbacher graduated. He took a job at Bear Stearns.

On Wall Street, the math geeks are known as quants. They’re the ones who create sophisticated trading algorithms that can ingest vast amounts of market data and then form buy and sell decisions in milliseconds. Hammerbacher was a quant. After about 10 months, he got back in touch with Zuckerberg, who offered him the Facebook job in California. That’s when Hammerbacher redirected his quant proclivities toward consumer technology. He became, as it were, a Want.

At social networking companies, Wants may sit among the computer scientists and engineers, but theirs is the central mission: to poke around in data, hunt for trends, and figure out formulas that will put the right ad in front of the right person. Wants gauge the personality types of customers, measure their desire for certain products, and discern what will motivate people to act on ads. “The most coveted employee in Silicon Valley today is not a software engineer. It is a mathematician,” says Kelman, the Redfin CEO. “The mathematicians are trying to tickle your fancy long enough to see one more ad.”

Sometimes the objective is simply to turn people on. Zynga, the maker of popular Facebook games such as CityVille and FarmVille, collects 60 billion data points per day—how long people play games, when they play them, what they’re buying, and so forth. The Wants (Zynga’s term is “data ninjas”) troll this information to figure out which people like to visit their friends’ farms and cities, the most popular items people buy, and how often people send notes to their friends. Discovery: People enjoy the games more if they receive gifts from their friends, such as the virtual wood and nails needed to build a digital barn. As for the poor folks without many friends who aren’t having as much fun, the Wants came up with a solution. “We made it easier for those players to find the parts elsewhere in the game, so they relied less on receiving the items as gifts,” says Ken Rudin, Zynga’s vice-president for analytics.

These consumer-targeting operations look a lot like what quants do on Wall Street. A Want system, for example, might watch what someone searches for on Google, what they write about in Gmail, and the websites they visit. “You get all this data and then build very rapid decision-making models based on their history and commercial intent,” says Will Price, CEO of Flite, an online ad service. “You have to make all of those calculations before the Web page loads.”

Ultimately, ad-tech companies are giving consumers what they desire and, in many cases, providing valuable services. Google delivers free access to much of the world’s information along with free maps, office software, and smartphone software. It also takes profits from ads and directs them toward tough engineering projects like building cars that can drive themselves and sending robots to the moon. The Era of Ads also gives the Wants something they yearn for: a ticket out of Nerdsville. “It lets people that are left- brain leaning expand their career opportunities,” says Doug Mack, CEO of One Kings Lane, a daily deal site that specializes in designer goods. “People that might have been in engineering can go into marketing, business development, and even sales. They can get on the leadership track.” And while the Wants plumb the depths of the consumer mind and advance their own careers, investors are getting something too, at least on paper: almost unimaginable valuations. Just since the fourth quarter, Zynga has risen 81 percent in value, to a cool $8 billion, according to Nyppex.

No one is suggesting that the top tier of ad-centric companies—Facebook, Google—is going down should the bubble pop. As for the next tier or two down, where a profusion of startups is piling into every possible niche involving social networking and ads—the fate of those companies is anybody’s guess. Among the many unveilings in March, one stood out: An app called Color, made by a seven-month-old startup of the same name. Color lets people take and store their pictures. More than that, it uses geolocation and ambient-noise-matching technology to figure out where a person is and then automatically shares his photos with other nearby people and vice versa. People at a concert, for example, could see photos taken by all the other people at that concert. The same goes for birthday parties, sporting events, or a night out at a bar. The app also shares photos among your friends in the Color social network, so you can see how Jane is spending her vacation or what John ate for breakfast, if he bothered to take a photo of it.

Whether Color ends up as a profitable app remains to be seen. The company has yet to settle on a business model, although its executives say it’ll probably incorporate some form of local advertising. Figuring out all those location-based news feeds on the fly requires serious computational power, and that part of the business is headed by Color’s math wizard and chief product officer, DJ Patil.

Patil’s Silicon Valley pedigree is impeccable. His father, Suhas Patil, emigrated from India and founded the chip company Cirrus Logic (CRUS). DJ struggled in high school, did some time at a junior college, and through force of will decided to get good at math. He made it into the University of California at San Diego, where he took every math course he could. He became a theoretical math guru and went on to research weather patterns, the collapse of sardine populations, the formation of sand dunes, and, during a stint for the Defense Dept., the detection of biological weapons in Central Asia. “All of these things were about how to use science and math to achieve these broader means,” Patil says. Eventually, Silicon Valley lured him back. He went to work for eBay (EBAY), creating an antifraud system for the retail site. “I took ideas from the bioweapons threat anticipation project,” he says. “It’s all about looking at a network and your social interactions to find out if you’re good or bad.”

Patil, 36, agonized about his jump away from the one true path of Silicon Valley righteousness, doing gritty research worthy of his father’s generation. “There is a time in life where that kind of work is easy to do and a time when it’s hard to do,” he says. “With a kid and a family, it was getting hard.”

Having gone through a similar self-inquiry, Hammerbacher doesn’t begrudge talented technologists like Patil for plying their trade in the glitzy land of networked photo sharing. The two are friends, in fact; they’ve gotten together to talk about data and the challenges in parsing vast quantities of it. At social networking companies, Hammerbacher says, “there are some people that just really buy the mission—connecting people. I don’t think there is anything wrong with those people. But it just didn’t resonate with me.”

After quitting Facebook in 2008, Hammerbacher surveyed the science and business landscape and saw that all types of organizations were running into similar problems faced by consumer Web companies. They were producing unprecedented amounts of information—DNA sequences, seismic data for energy companies, sales information—and struggling to find ways to pull insights out of the data. Hammerbacher and his fellow Cloudera founders figured they could redirect the analytical tools created by Web companies to a new pursuit, namely bringing researchers and businesses into the modern age.

Cloudera is essentially trying to build a type of operating system, à la Windows, for examining huge stockpiles of information. Where Windows manages the basic functions of a PC and its software, Cloudera’s technology helps companies break data into digestible chunks that can be spread across relatively cheap computers. Customers can then pose rapid-fire questions and receive answers. But instead of asking what a group of friends “like” the most on Facebook, the customers ask questions such as, “What gene do all these cancer patients share?”

Eric Schadt, the chief scientific officer at Pacific Biosciences, a maker of genome sequencing machines, says new-drug discovery and cancer cures depend on analytical tools. Companies using Pacific Bio’s machines will produce mountains of information every day as they sequence more and more people. Their goal: to map the complex interactions among genes, organs, and other body systems and raise questions about how the interactions result in certain illnesses—and cures. The scientists have struggled to build the analytical tools needed to perform this work and are looking to Silicon Valley for help. “It won’t be old school biologists that drive the next leaps in pharma,” says Schadt. “It will be guys like Jeff who understand what to do with big data.”

Even if Cloudera doesn’t find a cure for cancer, rid Silicon Valley of ad-think, and persuade a generation of brainiacs to embrace the adventure that is business software, Price argues, the tech industry will have the same entrepreneurial fervor of yesteryear. “You can make a lot of jokes about Zynga and playing FarmVille, but they are generating billions of dollars,” the Flite CEO says. “The greatest thing about the Valley is that people come and work in these super-intense, high-pressure environments and see what it takes to create a business and take risk.” A parade of employees has left Google and Facebook to start their own companies, dabbling in everything from more ad systems to robotics and publishing. “It’s almost a perpetual-motion machine,” Price says.

Perpetual-motion machines sound great until you remember that they don’t exist. So far, the Wants have failed to carry the rest of the industry toward higher ground. “It’s clear that the new industry that is building around Internet advertising and these other services doesn’t create that many jobs,” says Christophe Lécuyer, a historian who has written numerous books about Silicon Valley’s economic history. “The loss of manufacturing and design knowhow is truly worrisome.”

Dial back the clock 25 years to an earlier tech boom. In 1986, Microsoft, Oracle (ORCL), and Sun Microsystems went public. Compaq went from launch to the Fortune 500 in four years—the quickest run in history. Each of those companies has waxed and waned, yet all helped build technology that begat other technologies. And now? Groupon, which e-mails coupons to people, may be the fastest-growing company of all time. Its revenue could hit $4 billion this year, up from $750 million last year, and the startup has reached a valuation of $25 billion. Its technological legacy is cute e-mail.

There have always been foundational technologies and flashier derivatives built atop them. Sometimes one cycle’s glamour company becomes the next one’s hard-core technology company; witness Amazon.com’s (AMZN) transformation over the past decade from mere e-commerce powerhouse to e-commerce powerhouse and purveyor of cloud-computing capabilities to other companies. Has the pendulum swung too far? “It’s a safe bet that sometime in the next 20 months, the capital markets will close, the music will stop, and the world will look bleak again,” says Bridgescale Partners’ Cowan. “The legitimate concern here is that we are not diversifying, so that we have roots to fall back on when we enter a different part of the cycle.”

BY

BY