The true horror of modern hospital medicine is starting to be revealed.

440,000 deaths per year (up from 96,000 based on 1984 data) – one sixth of all deaths nationally, making preventable hospital error the third leading cause of death in the United States.

http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/12/04/to-make-hospitals-less-deadly-a-dose-of-data/?hp&rref=opinion&_r=1

To Make Hospitals Less Deadly, a Dose of Data

DECEMBER 4, 2013, 11:00 AM

By TINA ROSENBERG

Going to the hospital is supposed to be good for you. But in an alarming number of cases, it isn’t. And often it’s fatal. In fact it is the most dangerous thing most people will do.

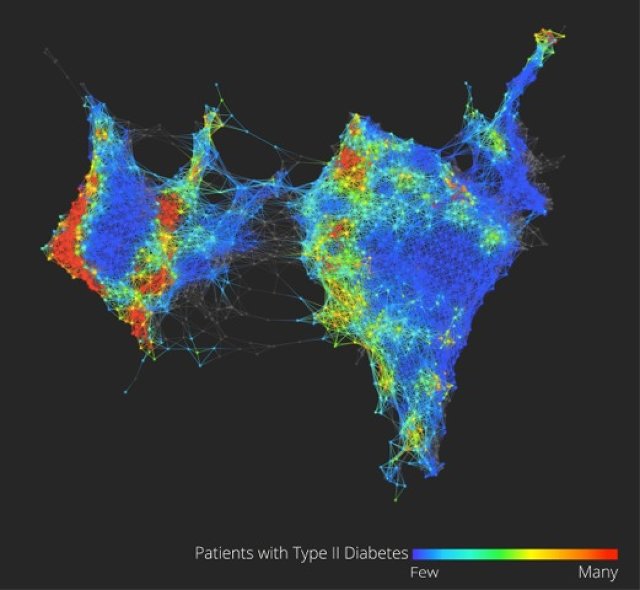

Until very recently, health care experts believed that preventable hospital error caused some 98,000 deaths a year in the United States — a figure based on 1984 data. But a new report from the Journal of Patient Safety using updated data holds such error responsible for many more deaths — probably around some 440,000 per year. That’s one-sixth of all deaths nationally, making preventable hospital error the third leading cause of death in the United States. And 10 to 20 times that many people suffer nonlethal but serious harm as a result of hospital mistakes.

Most of us decide which hospital to go to (that is, when we get to decide) with zero data about hospital safety. Information, however, is gradually reaching the public, and it can do more than just help us choose wisely. When patients can judge hospitals on their safety records, hospitals will become safer. Just as publishing health care prices will drive them down, publishing safety information will drive hospital safety up.

In theory, finding this information shouldn’t be a problem. Hospitals began to track errors seriously around 2000. The federal government’s Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services began collecting information on hospital quality in 2003, and since 2005 has been posting information on the website Hospital Compare. Many states have their own websites.

Other organizations compile this information as well, such as Consumers Union’s Consumer Reports (subscription required), which scores hospitals on their safety and the quality of care. The Leapfrog Group, which represents employer purchasers of health care, scores hospitals on safety measures. (The hospital ranking site probably most familiar to readers, U.S. News’ Best Hospitals rankings, describes its mission as a very different one — to help patients with very difficult problems choose hospitals.)

All of these groups measure different things, which is why a hospital can rank near the top on one list and near the bottom on another. Most groups make money by charging hospitals to use their logo and ratings in their publicity. Consumer Reports is an exception — it doesn’t allow hospitals to advertise its rankings.

“There is no longer a question of whether or not people have a right to information about quality, and that hospitals should be transparent and accountable,” said Debra L. Ness, the president of the National Partnership for Women and Families. Ness is on the board of the National Quality Forum, the organization that sets standards for evaluating health care safety and quality. “It’s not so much any longer a debate about whether — it’s more about how.”

But so far, the answer to the question of how is “slowly.” There is a big advance coming — Hospital Compare plans to begin reporting on rates of MRSA (or methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, a drug-resistant bacteria) and C-diff (Clostridium difficile) infections this month. These are dangerous, high-prevalence infections — crucial safety issues to track. But they are an exception on Hospital Compare. Much of what the public wants to know isn’t there — and a lot of what’s there isn’t meaningful.

What’s your hospital’s rate of surgical site infection? You can find out if you live in California or Pennsylvania — states that collect exhaustive information on hospital infections and post it. The rest of us are out of luck. Hospital Compare will tell you only about colon surgery or abdominal hysterectomy — no knee replacement, heart bypass or any other surgery. How often does your local hospital leave a foreign object (like a surgical sponge) inside a patient? Or administer the wrong type of blood? Or allow a patient to develop a serious bed sore or a blood clot? Hospital Compare is now listing only old data for these errors, and has stopped updating those measures on the site.

What about the hospital’s record at preventing re-admission in the 30 days after discharge? We can find that out for Medicare patients (the data comes from Medicare claims), but not for the rest of us. “Hospital Compare has a lot of bells and whistles but underneath it is nothing,” said Leah Binder, the chief executive of The Leapfrog Group. “Most hospitals are rated as average on every measure, and most measures are not things of great interest. We’re further along, but we’re really in the dark ages on reporting information in a way the public can use.”

Measuring hospital safety is hard. Comparison, of course, requires everyone to be using the same measures — so how to reconcile the many variations hospitals use? And how do we know a measurement actually tells us what we think it does?

It’s easiest to measure how often hospitals carry out processes that are recognized to be best practice, such as whether the patient got treatment to prevent blood clots after certain types of surgery, or whether the patient’s temperature was kept steady in the operating room. Hospitals track such processes for their own internal quality controls.

This kind of process information dominates Hospital Compare and some of the independent rating organizations. (U.S. News’ rankings lean heavily on a hospital’s reputation, which earns it heavy criticism.)

But tracking processes doesn’t produce the kind of information patients need. Hospitals are doing so well on these measures they are topping out, offering no way to compare them. Some of the measures are only loosely related to patient outcomes. For example, Hospital Compare shows that the national average for the practice of discontinuing prophylactic antibiotics within 24 hours after surgery is 97 percent. Top marks — but there is little evidence showing that this practice is linked to fewer surgical site infections. And it’s outcomes that count.

Why doesn’t Hospital Compare list more outcomes? Hospitals argue — and they are right — that it is much more expensive and technically difficult to develop outcome measures than process measures. “We need measures that have scientific reliability and validity,” said Nancy Foster, the American Hospital Association’s vice president of quality and patient safety policy. “Hospitals need the engagement of medical staff. If medical staff doesn’t find the data credible then you lose them — they won’t be there in the quality improvement. “

But at times it seems as if hospitals aren’t trying very hard. They like to report process measures on which they score well. But with 440,000 deaths from hospital error per year, their record is poor on key safety outcomes. This somewhat dampens their enthusiasm for public reporting. And what hospitals want matters a lot. “At the end of the day, the providers have to implement this,” said Ness. “There has to be a reasonable amount of buy-in for it to work well.”

“If you just looked at Hospital Compare’s process measures, you’d assume that all hospitals in this country are doing extremely well,” said Binder. “This is misleading to the public because of the politics behind the scene of the website. Lobbyists for providers have been very effective at making sure what gets reported doesn’t have much teeth.”

Hospital Compare chooses what to display mainly using guidelines set by the National Quality Forum, which was established in 1999 in response to a government commission on consumer protection in health care. At the Quality Forum, groups representing health care consumers — patients and the corporations who pay for health care — are represented on all committees, and they hold a guaranteed majority on the most important committee. But patients can’t match the clout of the providers. “Hospitals are ever-present in this work,” said Lisa McGiffert, who is director of the Safe Patient Project at the Consumers Union and has been a consumer representative on several Quality Forum committees. “They have lobbyists all over Congress and administration folks. They outnumbered us on the committees that I have been on at N.Q.F. When I was on the infections committee I was rolled over constantly.”

In a December 2011 meeting, the Measurement Application Partnership, a committee run by the Quality Forum, voted — over the objection of consumer and purchaser representatives — not to endorse reporting on several different serious hospital errors that were already on Hospital Compare. Hospital Compare then stopped updating data on air embolism, sponges or instruments left in a patient, serious bed sores and blood clots, among other events.

No one thought the raw data was unfair to hospitals — the data probably undercounted the number of hospital errors, said Foster. But hospitals argued that in some cases, the per-hospital numbers were so small the differences between hospitals might have been random, a conclusion supported by an independent review. (Hospitals have fought changes that would make reporting more complete — so it takes chutzpah to argue that the numbers are too small to publish.) “We agree with the concept,” Foster said. “But the way the measures are executed makes them very unreliable and, we believe, invalid. You don’t know that what you are looking at is an accurate representation of a hospital’s performance.”

Advocates for health care consumers argued that it didn’t matter — just knowing the number of errors was important. “Do you as an American have the right to know if the hospital down the street left an object in a patient?” said Binder. “That information has now been taken out of the hands of the consumer by lobbyists. We should always tilt towards transparency.”

Poor or irrelevant data keeps patients from finding the information they need. Another problem is that the data that’s there isn’t presented in a way people can easily use.

Hospital Compare cuts very thick slices. There’s below average, above average and average, which is the score of the vast majority of hospitals. And most patients simply don’t know about Hospital Compare. That’s not the government’s fault, but it does illustrate the need for translator organizations such as Consumer Reports — which has five categories, not three — and Leapfrog, which issues letter grades, with more detail available for those who want it.

Leapfrog’s twice-yearly data release gets a lot of coverage. McGiffert said that when Consumer Reports first came out with ratings for central-line and surgical site infections, some hospitals protested that the data was wrong. But it was the same data hospitals had submitted for state reports. “We were using data that had already been on state websites, but nobody had paid attention to it,” she said. “Agencies are never going to do a media push when they publish these.”

That media push reaches more patients, and it forces hospitals to focus on safety. “These are a major factor in getting hospitals’ attention,” said McGiffert. She said that hospitals in states that required public reporting were far more likely to adopt quality-improvement practices.

Binder said that except for advances in doctors’ using computers to enter treatment orders, hospital safety records, as a group, are not improving. This is hardly surprising. What gets measured gets done, and many aspects of safety are still not even measured. The Journal of Patient Safety study found 210,000 “detectable” deaths per year — the number they eventually fixed on of 440,000 reflected the estimate that half or two-thirds of all such deaths are never counted. “That’s a big range,” said Binder. “It sounds so high, but what more frightening is that we still don’t know. Nobody’s counting the bodies.”

Join Fixes on Facebook and follow updates on twitter.com/nytimesfixes. To receive e-mail alerts for Fixes columns, sign up here.

Tina Rosenberg won a Pulitzer Prize for her book “The Haunted Land: Facing Europe’s Ghosts After Communism.” She is a former editorial writer for The Times and the author, most recently, of “Join the Club: How Peer Pressure Can Transform the World” and the World War II spy story e-book “D for Deception.”

By TINA ROSENBERG

Going to the hospital is supposed to be good for you. But in an alarming number of cases, it isn’t. And often it’s fatal. In fact it is the most dangerous thing most people will do.

Until very recently, health care experts believed that preventable hospital error caused some 98,000 deaths a year in the United States — a figure based on 1984 data. But a new report from the Journal of Patient Safety using updated data holds such error responsible for many more deaths — probably around some 440,000 per year. That’s one-sixth of all deaths nationally, making preventable hospital error the third leading cause of death in the United States. And 10 to 20 times that many people suffer nonlethal but serious harm as a result of hospital mistakes.

Most of us decide which hospital to go to (that is, when we get to decide) with zero data about hospital safety. Information, however, is gradually reaching the public, and it can do more than just help us choose wisely. When patients can judge hospitals on their safety records, hospitals will become safer. Just as publishing health care prices will drive them down, publishing safety information will drive hospital safety up.

In theory, finding this information shouldn’t be a problem. Hospitals began to track errors seriously around 2000. The federal government’s Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services began collecting information on hospital quality in 2003, and since 2005 has been posting information on the website Hospital Compare. Many states have their own websites.

Other organizations compile this information as well, such as Consumers Union’s Consumer Reports (subscription required), which scores hospitals on their safety and the quality of care. The Leapfrog Group, which represents employer purchasers of health care, scores hospitals on safety measures. (The hospital ranking site probably most familiar to readers, U.S. News’ Best Hospitals rankings, describes its mission as a very different one — to help patients with very difficult problems choose hospitals.)

All of these groups measure different things, which is why a hospital can rank near the top on one list and near the bottom on another. Most groups make money by charging hospitals to use their logo and ratings in their publicity. Consumer Reports is an exception — it doesn’t allow hospitals to advertise its rankings.

“There is no longer a question of whether or not people have a right to information about quality, and that hospitals should be transparent and accountable,” said Debra L. Ness, the president of the National Partnership for Women and Families. Ness is on the board of the National Quality Forum, the organization that sets standards for evaluating health care safety and quality. “It’s not so much any longer a debate about whether — it’s more about how.”

But so far, the answer to the question of how is “slowly.” There is a big advance coming — Hospital Compare plans to begin reporting on rates of MRSA (or methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, a drug-resistant bacteria) and C-diff (Clostridium difficile) infections this month. These are dangerous, high-prevalence infections — crucial safety issues to track. But they are an exception on Hospital Compare. Much of what the public wants to know isn’t there — and a lot of what’s there isn’t meaningful.

What’s your hospital’s rate of surgical site infection? You can find out if you live in California or Pennsylvania — states that collect exhaustive information on hospital infections and post it. The rest of us are out of luck. Hospital Compare will tell you only about colon surgery or abdominal hysterectomy — no knee replacement, heart bypass or any other surgery. How often does your local hospital leave a foreign object (like a surgical sponge) inside a patient? Or administer the wrong type of blood? Or allow a patient to develop a serious bed sore or a blood clot? Hospital Compare is now listing only old data for these errors, and has stopped updating those measures on the site.

What about the hospital’s record at preventing re-admission in the 30 days after discharge? We can find that out for Medicare patients (the data comes from Medicare claims), but not for the rest of us. “Hospital Compare has a lot of bells and whistles but underneath it is nothing,” said Leah Binder, the chief executive of The Leapfrog Group. “Most hospitals are rated as average on every measure, and most measures are not things of great interest. We’re further along, but we’re really in the dark ages on reporting information in a way the public can use.”

Measuring hospital safety is hard. Comparison, of course, requires everyone to be using the same measures — so how to reconcile the many variations hospitals use? And how do we know a measurement actually tells us what we think it does?

It’s easiest to measure how often hospitals carry out processes that are recognized to be best practice, such as whether the patient got treatment to prevent blood clots after certain types of surgery, or whether the patient’s temperature was kept steady in the operating room. Hospitals track such processes for their own internal quality controls.

This kind of process information dominates Hospital Compare and some of the independent rating organizations. (U.S. News’ rankings lean heavily on a hospital’s reputation, which earns it heavy criticism.)

But tracking processes doesn’t produce the kind of information patients need. Hospitals are doing so well on these measures they are topping out, offering no way to compare them. Some of the measures are only loosely related to patient outcomes. For example, Hospital Compare shows that the national average for the practice of discontinuing prophylactic antibiotics within 24 hours after surgery is 97 percent. Top marks — but there is little evidence showing that this practice is linked to fewer surgical site infections. And it’s outcomes that count.

Why doesn’t Hospital Compare list more outcomes? Hospitals argue — and they are right — that it is much more expensive and technically difficult to develop outcome measures than process measures. “We need measures that have scientific reliability and validity,” said Nancy Foster, the American Hospital Association’s vice president of quality and patient safety policy. “Hospitals need the engagement of medical staff. If medical staff doesn’t find the data credible then you lose them — they won’t be there in the quality improvement. “

But at times it seems as if hospitals aren’t trying very hard. They like to report process measures on which they score well. But with 440,000 deaths from hospital error per year, their record is poor on key safety outcomes. This somewhat dampens their enthusiasm for public reporting. And what hospitals want matters a lot. “At the end of the day, the providers have to implement this,” said Ness. “There has to be a reasonable amount of buy-in for it to work well.”

“If you just looked at Hospital Compare’s process measures, you’d assume that all hospitals in this country are doing extremely well,” said Binder. “This is misleading to the public because of the politics behind the scene of the website. Lobbyists for providers have been very effective at making sure what gets reported doesn’t have much teeth.”

Hospital Compare chooses what to display mainly using guidelines set by the National Quality Forum, which was established in 1999 in response to a government commission on consumer protection in health care. At the Quality Forum, groups representing health care consumers — patients and the corporations who pay for health care — are represented on all committees, and they hold a guaranteed majority on the most important committee. But patients can’t match the clout of the providers. “Hospitals are ever-present in this work,” said Lisa McGiffert, who is director of the Safe Patient Project at the Consumers Union and has been a consumer representative on several Quality Forum committees. “They have lobbyists all over Congress and administration folks. They outnumbered us on the committees that I have been on at N.Q.F. When I was on the infections committee I was rolled over constantly.”

In a December 2011 meeting, the Measurement Application Partnership, a committee run by the Quality Forum, voted — over the objection of consumer and purchaser representatives — not to endorse reporting on several different serious hospital errors that were already on Hospital Compare. Hospital Compare then stopped updating data on air embolism, sponges or instruments left in a patient, serious bed sores and blood clots, among other events.

No one thought the raw data was unfair to hospitals — the data probably undercounted the number of hospital errors, said Foster. But hospitals argued that in some cases, the per-hospital numbers were so small the differences between hospitals might have been random, a conclusion supported by an independent review. (Hospitals have fought changes that would make reporting more complete — so it takes chutzpah to argue that the numbers are too small to publish.) “We agree with the concept,” Foster said. “But the way the measures are executed makes them very unreliable and, we believe, invalid. You don’t know that what you are looking at is an accurate representation of a hospital’s performance.”

Advocates for health care consumers argued that it didn’t matter — just knowing the number of errors was important. “Do you as an American have the right to know if the hospital down the street left an object in a patient?” said Binder. “That information has now been taken out of the hands of the consumer by lobbyists. We should always tilt towards transparency.”

Poor or irrelevant data keeps patients from finding the information they need. Another problem is that the data that’s there isn’t presented in a way people can easily use.

Hospital Compare cuts very thick slices. There’s below average, above average and average, which is the score of the vast majority of hospitals. And most patients simply don’t know about Hospital Compare. That’s not the government’s fault, but it does illustrate the need for translator organizations such as Consumer Reports — which has five categories, not three — and Leapfrog, which issues letter grades, with more detail available for those who want it.

Leapfrog’s twice-yearly data release gets a lot of coverage. McGiffert said that when Consumer Reports first came out with ratings for central-line and surgical site infections, some hospitals protested that the data was wrong. But it was the same data hospitals had submitted for state reports. “We were using data that had already been on state websites, but nobody had paid attention to it,” she said. “Agencies are never going to do a media push when they publish these.”

That media push reaches more patients, and it forces hospitals to focus on safety. “These are a major factor in getting hospitals’ attention,” said McGiffert. She said that hospitals in states that required public reporting were far more likely to adopt quality-improvement practices.

Binder said that except for advances in doctors’ using computers to enter treatment orders, hospital safety records, as a group, are not improving. This is hardly surprising. What gets measured gets done, and many aspects of safety are still not even measured. The Journal of Patient Safety study found 210,000 “detectable” deaths per year — the number they eventually fixed on of 440,000 reflected the estimate that half or two-thirds of all such deaths are never counted. “That’s a big range,” said Binder. “It sounds so high, but what more frightening is that we still don’t know. Nobody’s counting the bodies.”

Join Fixes on Facebook and follow updates on twitter.com/nytimesfixes. To receive e-mail alerts for Fixes columns, sign up here.

Tina Rosenberg won a Pulitzer Prize for her book “The Haunted Land: Facing Europe’s Ghosts After Communism.” She is a former editorial writer for The Times and the author, most recently, of “Join the Club: How Peer Pressure Can Transform the World” and the World War II spy story e-book “D for Deception.”