Missed the presentation, but caught the slide show… very cool, though still too doctor centric.

Doctors should not be involved in the delivery of population health because it’s not that hard…

Missed the presentation, but caught the slide show… very cool, though still too doctor centric.

Doctors should not be involved in the delivery of population health because it’s not that hard…

http://www.forbes.com/sites/davidshaywitz/2014/07/04/google-co-founders-to-healthcare-were-just-not-that-into-you/

I write about entrepreneurial innovation in medicine.

Opinions expressed by Forbes Contributors are their own.

At his yearly CEO summit, noted VC Vinod Khosla spoke with Google co-foundersSergey Brin and Larry Page (file under “King, Good To Be The”).

Towards the end of a wide-ranging conversation that encompassed driverless cars, flying wind turbines, and high-altitude balloons providing internet access, Khosla began to ask about health.

Specifically, Khosla wondered whether they could “imagine Google becoming a health company? Maybe a larger business than the search business or the media business?”

Their response, surprisingly, was basically, “no.” While glucose-sensing contact lenses might be “very cool,” in the words of Larry Page, Brin notes that,

“Generally, health is just so heavily regulated. It’s just a painful business to be in. It’s just not necessarily how I want to spend my time. Even though we do have some health projects, and we’ll be doing that to a certain extent. But I think the regulatory burden in the U.S. is so high that think it would dissuade a lot of entrepreneurs.”

Adds Page,

“We have Calico, obviously, we did that with Art Levinson, which is pretty independent effort. Focuses on health and longevity. I’m really excited about that. I am really excited about the possibility of data also, to improve health. But that’s– I think what Sergey’s saying, it’s so heavily regulated. It’s a difficult area. I can give you an example. Imagine you had the ability to search people’s medical records in the U.S.. Any medical researcher can do it. Maybe they have the names removed. Maybe when the medical researcher searches your data, you get to see which researcher searched it and why. I imagine that would save 10,000 lives in the first year. Just that. That’s almost impossible to do because of HIPAA. I do worry that we regulate ourselves out of some really great possibilities that are certainly on the data-mining end.”

Khosla then asked a question about a use case involving one of my favorite portfolio companies of his, Ginger.io, related to the monitoring of a patient’s psychiatric state.

Responded Page, “I was talking to them about that last night. It was cool.”

That pretty much captures Brin and Page’s view of healthcare – fun to work on a few “cool” projects, but beyond that, the regulatory challenges are just too great to warrant serious investment.

(To be clear, Brin and Page emphasized their personal distance from Google Ventures, which has conspicuously pursued a range of health-related investments. “Medicine needs to come out of the dark ages,” Google Ventures Managing Partner Bill Maris recently told Re/code.)

On the face of it, it’s pretty amazing that a company that doesn’t think twice about tackling absurdly challenging scientific projects (eg driverless cars) is brought to its knees by the prospect of dealing with the byzantine regulation around healthcare (and more generally, our “calcified hairball” system of care, as VC Esther Dyson has put it). A similar sentiment has been expressed by VC and Uber-investor Bill Gurley as well; evidently taking on taxi and limousine commissions is more palatable than taking on the healthcare establishment.

Yet others – with eyes wide open – are taking on the challenge. AthenaHealth’s Jonathan Bush, for instance, is maddened by the challenges of regulatory capture (see my WSJ review of his book here), yet he shows up each day to fight the battle.

Similarly, while I’ve not always agreed with Khosla’s perspective on algorithims, I’ve consistently admired his willingness to enter the fray (see here and here).

This morning on Twitter, he asked whether his willingness to invest in healthcare means he’s courageous (as I suggested) or naïve.

The answer, I imagine, is probably both. The challenges in healthcare, especially regarding regulation, are real, and disruption is hard to come by. As Brown University emergency physician Megan Ranney comments, there are “big risks, lots of roadblocks” but also “huge potential for humankind.”

I suspect the key to overcoming the regulatory roadblocks will be making the use cases more persuasive and immediate. After all, most people have the enlightened self-interest to embrace life-saving innovations (anti-vaxers notwithstanding).

The challenge is that to this point, the benefits of technology generally seem less than persuasive – the tech seems “cool,” as Page and Brin might say, but not exactly convincing. I’m not just talking about Google Glass (which perhaps defines the genre) and Google’s contact lenses (I’ve not met many experts who’ve bought into this technology), but also approaches like 23andMe. When they ran up against regulators, there wasn’t exactly an outcry, “this technology has transformed my life and now you’re shutting it down.” If only.

In contrast, efforts to shut down Uber typically generate far more impassioned protests. Why? Because it’s immediately apparent to users how Uber improves their lives. To use the service once is to be convinced.

What healthcare technology needs is to find a way to be similarly indispensable. Page may cite the potential to save 10,000 lives, but the challenge is to convince anyone this applies to their own N of 1. More directed examples of instances where technology could immediately impact lives, and could impact more were it not for oppressive regulation, would go a long way to rolling back the regulations that seem to impede progress.

Rather than focusing on the thousands of lives that could be saved in an imagined future, technologists would do well to provide a compelling demonstration of what big data and sophisticated analytics can achieve for the health of discrete individuals in the present, even with current limitations; success here could help innovative entrepreneurs push back on antiquated regulations, and bring healthcare delivery into the modern age while ushering in a new era in biomedical research driven by access to rich coherent datasets.

The truth is, Page is probably right about the underlying opportunity. In particular, as I’ve long-argued, there’s tremendous potential to be found by thoughtfully combining comprehensive genomic and rich phenotypic data – immediate opportunities to impact clinical care, and the chance for a longer-term impact on scientific understanding.

I’m perhaps more optimistic than Page is, however, both about our collective ability to succeed meaningfully even within the constraints of our existing system, and about the ability of demonstrated success to move even the most intransigent stakeholders.

Hospitals and insurers need to be mindful about crossing the “creepiness line” on how much to pry into their patients’ lives with big data.

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-06-26/hospitals-soon-see-donuts-to-cigarette-charges-for-health.html

You may soon get a call from your doctor if you’ve let your gym membership lapse, made a habit of picking up candy bars at the check-out counter or begin shopping at plus-sized stores.

That’s because some hospitals are starting to use detailed consumer data to create profiles on current and potential patients to identify those most likely to get sick, so the hospitals can intervene before they do.

Information compiled by data brokers from public records and credit card transactions can reveal where a person shops, the food they buy, and whether they smoke. The largest hospital chain in the Carolinas is plugging data for 2 million people into algorithms designed to identify high-risk patients, while Pennsylvania’s biggest system uses household and demographic data. Patients and their advocates, meanwhile, say they’re concerned that big data’s expansion into medical care will hurt the doctor-patient relationship and threaten privacy.

Related:

“It is one thing to have a number I can call if I have a problem or question, it is another thing to get unsolicited phone calls. I don’t like that,” said Jorjanne Murry, an accountant in Charlotte, North Carolina, who has Type 1 diabetes. “I think it is intrusive.”

Acxiom Corp. (ACXM) and LexisNexis are two of the largest data brokers who collect such information on individuals. Acxiom says their data is supposed to be used only for marketing, not for medical purposes or to be included in medical records. LexisNexis said it doesn’t sell consumer information to health insurers for the purposes of identifying patients at risk.

Much of the information on consumer spending may seem irrelevant for a hospital or doctor, but it can provide a bigger picture beyond the brief glimpse that doctors get during an office visit or through lab results, said Michael Dulin, chief clinical officer for analytics and outcomes at Carolinas HealthCare System.

Carolinas HealthCare System operates the largest group of medical centers in North Carolina andSouth Carolina, with more than 900 care centers, including hospitals, nursing homes, doctors’ offices and surgical centers. The health system is placing its data, which include purchases a patient has made using a credit card or store loyalty card, into predictive models that give a risk score to patients.

Special Report: Putting Patient Privacy at Risk

Within the next two years, Dulin plans for that score to be regularly passed to doctors and nurses who can reach out to high-risk patients to suggest interventions before patients fall ill.

For a patient with asthma, the hospital would be able to score how likely they are to arrive at the emergency room by looking at whether they’ve refilled their asthma medication at the pharmacy, been buying cigarettes at the grocery store and live in an area with a high pollen count, Dulin said.

The system may also score the probability of someone having a heart attack by considering factors such as the type of foods they buy and if they have a gym membership, he said.

“What we are looking to find are people before they end up in trouble,” said Dulin, who is also a practicing physician. “The idea is to use big data and predictive models to think about population health and drill down to the individual levels to find someone running into trouble that we can reach out to and try to help out.”

While the hospital can share a patient’s risk assessment with their doctor, they aren’t allowed to disclose details of the data, such as specific transactions by an individual, under the hospital’s contract with its data provider. Dulin declined to name the data provider.

If the early steps are successful, though, Dulin said he would like to renegotiate to get the data provider to share more specific details on patient spending with doctors.

“The data is already used to market to people to get them to do things that might not always be in the best interest of the consumer, we are looking to apply this for something good,” Dulin said.

While all information would be bound by doctor-patient confidentiality, he said he’s aware some people may be uncomfortable with data going to doctors and hospitals. For these people, the system is considering an opt-out mechanism that will keep their data private, Dulin said.

“You have to have a relationship, it just can’t be a phone call from someone saying ‘do this’ or it just feels creepy,” he said. “The data itself doesn’t tell you the story of the person, you have to use it to find a way to connect with that person.”

Murry, the diabetes patient from Charlotte, said she already gets calls from her health insurer to try to discuss her daily habits. She usually ignores them, she said. She doesn’t see what her doctors can learn from her spending practices that they can’t find out from her quarterly visits.

“Most of these things you can find out just by looking at the patient and seeing if they are overweight or asking them if they exercise and discussing that with them,” Murry said. “I think it is a waste of time.”

While the patients may gain from the strategy, hospitals also have a growing financial stake in knowing more about the people they care for.

Under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, known as Obamacare, hospital pay is becoming increasingly linked to quality metrics rather than the traditional fee-for-service model where hospitals were paid based on their numbers of tests or procedures.

As a result, the U.S. has begun levying fines against hospitals that have too many patients readmitted within a month, and rewarding hospitals that do well on a benchmark of clinical outcomes and patient surveys.

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, which operates more than 20 hospitals in Pennsylvania and a health insurance plan, is using demographic and household information to try to improve patients’ health. It says it doesn’t have spending details or information from credit card transactions on individuals.

The UPMC Insurance Services Division, the health system’s insurance provider, has acquired demographic and household data, such as whether someone owns a car and how many people live in their home, on more than 2 million of its members to make predictions about which individuals are most likely to use the emergency room or an urgent care center, said Pamela Peele, the system’s chief analytics officer.

Studies show that people with no children in the home who make less than $50,000 a year are more likely to use the emergency room, rather than a private doctor, Peele said.

UPMC wants to make sure those patients have access to a primary care physician or nurse practitioner they can contact before heading to the ER, Peele said. UPMC may also be interested in patients who don’t own a car, which could indicate they’ll have trouble getting routine, preventable care, she said.

Being able to predict which patients are likely to get sick or end up at the emergency room has become particularly valuable for hospitals that also insure their patients, a new phenomenon that’s growing in popularity. UPMC, which offers this option, would be able to save money by keeping patients out of the emergency room.

Obamacare prevents insurers from denying coverage because of pre-existing conditions or charging patients more based on their health status, meaning the data can’t be used to raise rates or drop policies.

“The traditional rating and underwriting has gone away with health-care reform,” said Robert Booz, an analyst at the technology research and consulting firm Gartner Inc. (IT) “What they are trying to do is proactive care management where we know you are a patient at risk for diabetes so even before the symptoms show up we are going to try to intervene.”

Hospitals and insurers need to be mindful about crossing the “creepiness line” on how much to pry into their patients’ lives with big data, he said. It could also interfere with the doctor-patient relationship.

The strategy “is very paternalistic toward individuals, inclined to see human beings as simply the sum of data points about them,” Irina Raicu, director of the Internet ethics program at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University, said in a telephone interview.

To contact the reporters on this story: Shannon Pettypiece in New York atspettypiece@bloomberg.net; Jordan Robertson in San Francisco atjrobertson40@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Reg Gale at rgale5@bloomberg.net Andrew Pollack

Woolf explained this disparity by citing the work of the British social epidemiologist Richard Wilkinson, who has proposed that income inequality generates adverse health effects even among the affluent. Wide gaps in income, Wilkinson argues, diminish our trust in others and our sense of community, producing, among other things, a tendency to underinvest in social infrastructure. Furthermore, Woolf told me, even wealthy Americans are not isolated from a lifestyle filled with oversized food portions, physical inactivity, and stress. Consider the example of paid parental leave, for which the United States ranks dead last among O.E.C.D. countries. It’s not hard to see how such policies might have implications for infant and child health.

Other countries have used their governments as instruments to improve health—including, but not limited to, the development of universal health insurance. Health-policy analysts have therefore considered the effect that different political systems have on public health. Most O.E.C.D. countries, for example, have parliamentary systems, where the party that wins the majority of seats in the legislature forms the government. Because of this overlap of the legislative and executive branches, parliamentary systems have fewer checks and balances—fewer of what Victor Fuchs, a health economist at Stanford, calls “choke points for special interests to block or reshape legislation,” such as filibusters or Presidential vetoes. In a parliamentary system, change can be enacted without extensive political negotiation—whereas the American system was designed, at least in part, to avoid the concentration of power that can produce such swift changes.

Most experts estimate that modern medical care delivered to individual patients—such as physician and hospital treatments covered by health insurance—has only been responsible for between ten and twenty-five percent of the improvements in life expectancy over the last century. The rest has come from changes in the social determinants of health, particularly in early childhood.

http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/elements/2014/06/why-america-is-losing-the-health-race.html

The second report, commissioned by the National Institutes of Health, and conducted by the National Research Council (NRC) and the Institute of Medicine (IOM), convened a panel of experts to examine health indicators in seventeen high-income countries. It found the United States in a similarly poor position: American men had the lowest life expectancy, and American women the second-lowest. In some ways, these reports were not news. As early as the nineteen-seventies, a group of leading health analysts had noted the discrepancy between American health spending and outcomes in a book called “Doing Better and Feeling Worse: Health in the United States.” From this perspective, the U.S. has been doing something wrong for a long time. But, as the first of these two reports shows, the gap is widening; despite spending more than any other country, America ranks very poorly in international comparisons of health. The second report may provide an answer—supporting the intuition long held by researchers that social circumstances, especially income, have a significant effect on health outcomes.

Americans’ health disadvantage actually begins at birth: the U.S. has the highest rates of infant mortality among high-income countries, and ranks poorly on other indicators such as low birth weight. In fact, children born in the United States have a lower chance of surviving to the age of five than children born in any other wealthy nation—a fact that will almost certainly come as a shock to most Americans. But what causes such poor health outcomes among American children, and how can those outcomes be improved? Public-health experts focus on the “social determinants of health”—factors that shape people’s health beyond their lifestyle choices and medical treatments. These include education, income, job security, working conditions, early-childhood development, food insecurity, housing, and the social safety net.

Steven Schroeder, the former president of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation—the largest philanthropic organization in the United States devoted to health issues—had a definitive answer to my question about why Americans might be less healthy than their developed-country counterparts. “Poverty,” he said. “The United States has proportionately more poor people, and the gap between rich and poor is widening.” Seventeen per cent of Americans live in poverty; the median figure for other O.E.C.D. countries is only nine percent. For three decades, America has had the highest rate of child poverty of any wealthy nation.

Steven Woolf, of Virginia Commonwealth University, who chaired the panel that produced the NRC-IOM report, also pointed to poverty when I asked him to explain the causes of America’s health disadvantage. “Could there possibly be a common thread that leads Americans to have higher rates of infant mortality, more deaths from car crashes and gun violence, more heart disease, more AIDS, and more premature deaths from drugs and alcohol? Is there some common denominator?” he asked. “One possibility is the way Americans, as a society, manage their affairs. Many Americans embrace rugged individualism and reject restrictions on behaviors that pose risks to health. There is less of a sense of solidarity, especially with vulnerable populations.” As a percentage of G.D.P., Woolf observed, the U.S. invests less than other wealthy countries in social programs like parental leave and early-childhood education, and there is strong resistance to paying taxes to finance such programs. The U.S. ranks first among O.E.C.D. countries in health-care expenditures, but as Elizabeth Bradley, a researcher at Yale, has documented, it ranks twenty-fifth in spending on social services.

The NRC-IOM report emphasized the effect of social forces on children and how those forces carry over to affect the health of adults, noting that American children are “more likely than children in peer countries to grow up in poverty” and that “poor social conditions during childhood precipitate a chain of adverse life events.” For example, of the seventeen wealthy democracies included in the report, the U.S. has the highest rates of adolescent pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases, and the second-highest prevalence of H.I.V. This platform of adverse health influences in childhood sets up the health disadvantage that remains pervasive for all age groups under seventy-five in the United States.

It seems likely that many Americans would respond to these figures—and to the role poverty plays in poor health outcomes—by assuming that the data for all Americans is being skewed downward by the health of the poorest. That is, they understand that poor Americans have worse health, and presume that, because the United States has more poor people than other wealthy countries, the average health looks worse. But one of the most interesting findings in the NRC-IOM report is that even white, college-educated, high-income Americans with healthy behaviors have worse health than their counterparts in other wealthy countries.

Woolf explained this disparity by citing the work of the British social epidemiologist Richard Wilkinson, who has proposed that income inequality generates adverse health effects even among the affluent. Wide gaps in income, Wilkinson argues, diminish our trust in others and our sense of community, producing, among other things, a tendency to underinvest in social infrastructure. Furthermore, Woolf told me, even wealthy Americans are not isolated from a lifestyle filled with oversized food portions, physical inactivity, and stress. Consider the example of paid parental leave, for which the United States ranks dead last among O.E.C.D. countries. It’s not hard to see how such policies might have implications for infant and child health.

Other countries have used their governments as instruments to improve health—including, but not limited to, the development of universal health insurance. Health-policy analysts have therefore considered the effect that different political systems have on public health. Most O.E.C.D. countries, for example, have parliamentary systems, where the party that wins the majority of seats in the legislature forms the government. Because of this overlap of the legislative and executive branches, parliamentary systems have fewer checks and balances—fewer of what Victor Fuchs, a health economist at Stanford, calls “choke points for special interests to block or reshape legislation,” such as filibusters or Presidential vetoes. In a parliamentary system, change can be enacted without extensive political negotiation—whereas the American system was designed, at least in part, to avoid the concentration of power that can produce such swift changes.

Whatever the political obstacles, a major explanation for America’s persistent health disadvantage is simply a lack of public awareness. “Little is likely to happen until the American public is informed about this issue,” the authors of the NRC-IOM report noted. “Why don’t Americans know that children born here are less likely to reach the age of five than children born in other high income countries?” Woolf asked. I suggested that perhaps people believe that the problem is restricted to other people’s children. He said, “We are talking about their children and their health too.”

The superior health outcomes achieved by other wealthy countries demonstrate that Americans are—to use the language of negotiators—“leaving years of life on the table.” The causes of this problem are many: poverty, widening income disparity, underinvestment in social infrastructure, lack of health insurance coverage and access to health care. Expanding insurance coverage under the Affordable Care Act will help, but pouring more money into health care is not the only answer. Most experts estimate that modern medical care delivered to individual patients—such as physician and hospital treatments covered by health insurance—has only been responsible for between ten and twenty-five percent of the improvements in life expectancy over the last century. The rest has come from changes in the social determinants of health, particularly in early childhood.

Self-interest may be a natural human trait, but when it comes to public health other countries are showing the U.S. that what appears at first to be an altruistic concern for the health and care of the most vulnerable—especially children—may well result in improved health for all members of a society, including the affluent. Until Americans find their way to understanding this dynamic, and figure out how to mobilize public opinion in its favor, they will all continue to lose out on better health and longer lives.

Allan S. Detsky (M.D., Ph.D.) is a general internist and a professor of Health Policy Management and Evaluation and of Medicine at the University of Toronto, where he was formerly physician-in-chief at Mount Sinai Hospital. He is a contributing writer for The Journal of the American Medical Association.

Photograph by Ashley Gilbertson /VII.

Vitality absolutely smash it across the board…

Must get on to these guys…..

PDF: Vitality_Recommendations2014_Report

PDF: InvestingInPrevention_Slides

Presentation: https://goto.webcasts.com/viewer/event.jsp?ei=1034543 (email: blackfriar@gmail.com)

From Forbes: http://www.forbes.com/sites/brucejapsen/2014/06/18/how-corporate-america-could-save-300-billion-by-measuring-health-like-financial-performance/

Bruce Japsen, Contributor

I write about health care and policies from the president’s hometown

The U.S. could save more than $300 billion annually if employers adopted strategies that promoted health, prevention of chronic disease and measured progress of “working-age” individuals like they did their financial performance, according to a new report.

The analysis, developed by some well-known public health advocates brought together and funded by The Vitality Institute, said employers could save $217 billion to $303 billion annually, or 5 to 7 percent of total U.S. annual health spending by 2023, by adopting strategies to help Americans head off “non-communicable” diseases like cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular and respiratory issues as well as mental health.

To improve, the report’s authors say companies should be reporting health metrics like BMI and other employee health statuses just like they regularly report earnings and how an increasing number of companies report sustainability. Corporations should be required to integrate health metrics into their annual reporting by 2025, the Vitality Institute said. A link to the entire report and its recommendations is here.

“Companies should consider the health of their employees as one of their greatest assets,” said Derek Yach, executive director of the Vitality Institute, a New York-based organization funded by South Africa’s largest health insurance company, Discovery Limited.

Those involved in the report say its recommendations come at a time the Affordable Care Act and employers emphasize wellness as a way to improve quality and reduce costs.

“Healthy workers are more productive, resulting in improved financial performance,” Yach said. “We’re calling on corporations to take accountability and start reporting health metrics in their financial and sustainability reports. We believe this will positively impact the health of both employees and the corporate bottom line.”

The Institute brought together a commission linked here that includes some executives from the health care industry and others who work in academia and business. Commissioners came from Microsoft (MSFT); the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; drug and medical device giant Johnson & Johnson (JNJ); health insurer Humana (HUM); and the U.S. Department of Health and Humana Services.

The Vitality Institute said up to 80 percent of non-communicable diseases can be prevented through existing “evidence-based methods” and its report encourages the nation’s policymakers and legislative leaders to increase federal spending on prevention science at least 10 percent by 2017.

“Preventable chronic diseases such as lung cancer, diabetes and heart disease are forcing large numbers of people to exit the workforce prematurely due to their own poor health or to care for sick relatives,” said William Rosenzweig, chair of the Vitality Institute Commission and an executive at Physic Ventures, which invests in health and sustainability projects. “Yet private employers spend less than two percent of their total health budgets on prevention. This trend will stifle America’s economic growth for decades to come unless health is embraced as a core value in society.”

Compelling discussion about new thinking about, and forms of government…

http://www.bbc.co.uk/podcasts/series/stw

Mon, 9 Jun 14

Duration:

42 mins

Tom Sutcliffe discusses whether Western states have anything to learn from countries like China and Singapore. Adrian Wooldridge argues that many governments have become bloated and there’s a global race to reinvent the state. In the past Britain was at the forefront of exporting ideas on how to run a country, as the Labour MP Tristram Hunt explains in his book on the legacy of empire. Charu Lata Hogg from Chatham House looks at the challenges to democracy in Thailand where the country is in political turmoil, and the journalist Anjan Sundaram spent a year in The Congo during the violent 2006 elections, and looks at day-to-day life in a failing state.

A big issue for the health system in Australia is that no-one’s in charge. Not the Commonwealth, not the states, not the private health insurance funds. Most provision is private: general practitioners are increasingly employed by for-profit chains, and before that, small business people. They respond to incentives designed by the Commonwealth government.

http://theconversation.com/did-the-health-reform-process-fail-now-well-never-know-27921

Yesterday was a sorry day in the long history of health reform in Australia. The Council of Australian Governments (COAG) Reform Council issued its five year score-keeper’s report on health reform progress. It will be the last such report, since the COAG Reform Council has been sacrificed on the altar of savings in the May budget, and we will no longer know how our governments are performing.

The COAG Reform Council paints some lipstick on the pig but overall reform results are poor in the health system. Compared to last year, Australians are waiting marginally longer for elective surgery, longer for community support in the home, and dramatically longer to get into residential aged care.

On the upside, we’re living slightly longer, having fewer heart attacks and the incidence of some cancers has reduced. The five-year trends for performance paint a similar picture to the year-on-year results.

It’s easy to conclude that the health reform process was a waste of time and money. But this is shortsighted. Many of the structural reforms focused on building the foundations of a health system that was on the verge of being able to deliver real improvements in patient care.

Kevin Rudd’s gab-fest of health reform talk in 2009 and early 2010 led to an alphabet soup of new health agencies, some investment in parts of the health system, more data in the public domain than we’ve ever seen but precious little in terms of real on-the-ground improvements.

But there were some important exceptions. The Rudd-appointed National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission identified a gap in availability of rehabilitation beds in the system. Without adequate rehabilitation care people were ending up in nursing homes when they could have been at home. Reform money helped to address that gap, although that funding was abruptly terminated in the 2014 budget.

Funding was also provided for better prevention programs and to reward improvements in waiting times where they occurred. Medicare Locals were created to provide a platform for improvements in primary care such as better after-hours services.

Running a health system is hard, improving it is even harder. But we have to improve every day just to stand still. The new treatments that are introduced every week put pressure on the health dollar. These new treatments, though, mean we’re living longer – so we get something for the extra money.

A big issue for the health system in Australia is that no-one’s in charge. Not the Commonwealth, not the states, not the private health insurance funds. Most provision is private: general practitioners are increasingly employed by for-profit chains, and before that, small business people. They respond to incentives designed by the Commonwealth government.

The pathology and radiology markets are also highly concentrated corporatised businesses. Around one-third of hospital beds are in private hospitals, and most of those are for-profit businesses as well.

The health reform process mainly concentrated on two aspects of the system: primary care and public hospitals. Primary care reform was mainly effected through the creation of Medicare Locals and GP Super Clinics.

Both were good ideas but flawed in implementation: some Super Clinics are still not open five years after the policy got underway. Medicare Locals were over-hyped by the previous government, wrapped up in red tape by the Commonwealth Health Department and as a result of the budget are being abolished and replaced by new organisations.

Public hospital reform had two elements. In most states it included increased local autonomy through introduction of local boards, and increased services with expanded rehab being the best example. At the national level it included a new alignment of Commonwealth and state interests in controlling hospital costs.

From June 1, 2014, the Commonwealth will meet 45% of the costs of increased hospital activity, but only up to an independently determined “efficient price”. This is a good reform, because could have ended the blame game between Commonwealth and states over money by locking the former into funding increased health state health spending. But these changes will be undone in 2017.

So come 2017, most evidence of health reform will have vanished. There will be some ongoing structures and services, but the big aspirations to address the big problems will have fizzled out.

The problems won’t go away, however. Innovation and system reform will still be required. If anyone is around to issue the next score-keeper’s report it will undoubtedly show worse performance, including longer waiting times, across the health system. There’ll then be more calls for reform and the whole cycle will start again, but with wasted years in the meantime.

Fish politics: The FDA’s updated policy on eating fish while pregnant

Eating fish presents difficult dilemmas (I evaluate them in five chapters of What to Eat).

This one is about asking pregnant women to weigh the benefits of fish-eating against the hazards of their toxic chemical contaminants to the developing fetus.

The Dietary Guidelines tell pregnant women to eat 2-to-3 servings of low-mercury fish per week (actually, it’s methylmercury that is of concern, but the FDA calls it mercury and I will too).

But to do that, pregnant women have to:

Only a few fish, all large predators, are high in mercury. The FDA advisory says these are:

What? This list leaves off the fifth large predator: Albacore (white) tuna. This tuna has about half the mercury as the other four, but still much more than other kinds of fish.

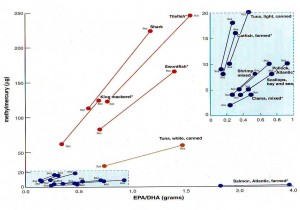

The figure below comes from the Institute of Medicine’s fish report. It shows that fish highest in omega-3 fatty acids, the ones that are supposed to promote neurological development in the fetus and cognitive development in infants, are also highest in mercury.

White tuna is the line toward the bottom. The ones in the blue boxes are all much lower in omega-3s and in mercury except for farmed Atlantic salmon (high in omega-3s, very low in mercury).

What’s going on here?

I think it is absurd to require pregnant women to know which fish to avoid. In supermarkets, fish can look pretty much alike and you cannot count on fish sellers to know the differences.

Other dilemmas:

That’s fish politics, for you.

The FDA documents:

According to Admiral William H. McRaven, if you want to change the world you must:

http://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2014/06/the-only-reason-anyone-would-eat-broccoli/372899/

What are you doing with the benzene you inhale? Just absorbing it, stocking up on sleepiness, dizziness, anemia, possibly leukemia? Or are you taking control and expunging it in your urine?

This week in the journal Cancer Prevention Research, scientists from Johns Hopkins and China’s Qidong Liver Cancer Institute report that daily consumption of a half-cup of “broccoli-sprout beverage”—a tea made with broccoli sprouts—produced rapid, sustained, high-level excretion of benzene in research subjects’ urine. Their conclusion, building on prior research, is that broccoli helps the human body break down benzene and excrete its byproducts. As benzene is a known human carcinogen commonly found in polluted air in both urban and rural areas, voiding it is an unmitigated virtue.

The broccoli-sprout beverage also increased the levels of the lung irritant acrolein, another common air pollutant, in the subjects’ urine.

So every alt-juice shop that sells a $14 broccoli-sprout smoothie on its “cleansing” merits is technically not entirely lying.

The broccoli-sprout beverage is understood to be a vehicle for the compound sulforaphane, which has been shown to have cancer-preventive qualities in animal studies, apparently by activating a molecule called NRF2 that enhances cells’ abilities to adapt to environmental toxins. In another study earlier this year, sulforaphane-rich broccoli sprout preparations decreased people’s nasal allergic responses to diesel exhaust particles.

The researchers found that among participants who drank the broccoli-sprout beverage, excretion of benzene increased 61 percent—beginning the first day and continuing throughout the 12-week study. Excretion of acrolein increased by 23 percent.

Outdoor air pollution is associated with cardiorespiratory mortality, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lung cancer, and overall decreased lung function. According to the World Health Organization, air pollution kills around seven million people every year. It might seem absurd to suggest putting the onus on individual dietary choices, but that’s basically what’s happening here. Environmental researchers call it chemoprevention. A quarter of the world is breathing unsafe air, and while government officials are hard at work implementing regulatory policies to improve air quality and reduce reliance on fossil fuels, which they surely are, we get to eat more broccoli.

“This study points to a frugal, simple, and safe means that can be taken by individuals,” said lead researcher Thomas Kensler, a professor at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, in a press statement, “to possibly reduce some of the long-term health risks associated with air pollution.”

Regular broccoli also contains sulforaphane, though in considerably lower quantities than the sprouts studied here, which the researchers found to be “the maximum tolerated dose.”

“The more bitter your broccoli, perhaps the better,” Kensler told The Wall Street Journal, adding that one would have to consume roughly 1.5 cups of broccoli every day to get the same amount consumed in this study—even more if it’s boiled, which is just no way to prepare broccoli.

Chemoprevention could empower people who live in areas with high levels of air pollution, and this study will provide leverage for broccoli-pushing parents everywhere. “Eat your broccoli, child, or the air will get you. Chemicals that the corporations put in the air will give you cancer. Finish it. The air is coming for you. Finish your broccoli. Eat your broccoli. Don’t you. No. Don’t you talk to me about policy reform. The only person you can count on in this world is yourself. Swallow. Eat it.”