Blue Zones employs evidence-based ways to help people live longer, better. The Company’s work is rooted in the New York Times best-selling books The Blue Zones and Thrive—both published by National Geographic books. In 2009, Blue Zones applied the tenets of the books to Albert Lea, MN and successfully raised life expectancy and lowered health care costs for city workers by 40%. Blue Zones takes a systematic, environmental approach to well-being which focuses on optimizing policy, building design, social networks, and the built environment. The Blue Zones Project is based on this innovative approach.

Category Archives: nutrition

Dementia Researchers Call for G-8 to Focus on Prevention

- 44 million people have dementia worldwide

- better diet, exercise, low blood pressure, not smoking and avoiding obesity present key aspects of preventing dementia

- Vitamins B6 and B12 and folic acid would cost pennies a day and slowed atrophy of gray matter in brain areas affected by Alzheimer’s disease, according to a study published in May by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Dementia Researchers Call for G-8 to Focus on Prevention

“About half of Alzheimer’s disease cases worldwide might be attributable to known risk factors,” they said in a statement before a G-8 meeting in London tomorrow to coordinate responses to the condition. “Taking immediate action on the known risk factors could perhaps prevent up to one-fifth of predicted new cases by 2025.”

The costs of dementia were estimated at $604 billion for 2010, the group said, and the number of cases is set to more than triple by 2050. The 111 signatories from 36 countries called on governments to back more research into prevention, and policies such as promotion of healthier diets. The G-8 are the U.K., U.S., Germany, France, Canada, Italy, Russiaand Japan.

“The choice is stark,” said Zaven Khachaturian, a signatory and editor-in-chief of U.S. journalAlzheimer’s & Dementia. “Either you invest money in creating this infrastructure for preventing or delaying dementia, or continue along the way. If we continue with the current trends, no country’s health-care system will be able to provide care.”

Cheap Vitamins

Alzheimer’s Disease International estimates that 44 million people worldwide have dementia, which will rise to 76 million in 2030 and 135 million by 2050, according to data from the group of Alzheimer’s associations.

About $40 billion has been invested in drug development efforts that haven’t produced effective new medicines, the researchers said in today’s statement. Even so, recent research suggests there may be cheap options to help tackle the problem.

A cocktail of vitamins B6 and B12 and folic acid would cost pennies a day and slowed atrophy of gray matter in brain areas affected by Alzheimer’s disease, according to a study published in May by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

About half the fall in deaths from conditions such as heart disease and stroke in the past 50 years resulted from modifying risk factors, according to the scientists advocating prevention. Taking a similar approach to dementia by encouraging middle-aged people to adopt healthy lifestyles may ward off the condition as it does other diseases and save “huge sums,” they said.

Healthy Lifestyle

A healthy lifestyle includes exercising; not smoking; following a diet rich in fruit, vegetables and fish; avoiding obesity, diabetes and excessive alcohol; and treating high blood pressure, the researchers said.

Other research is helping to identify people at risk. A person’s chance of getting dementia before age 65 may develop as early as adolescence, according to a study that suggests teens with high blood pressure or who drink excessively are at risk.

Other risk factors include stroke, use of antipsychotics, father’s dementia, drug intoxication, as well as short stature and low cognitive function, according to the study of Swedish men published by the journal JAMA Internal Medicine in August.

G-8 governments should set goals, stimulate more collaborative research, coordinate policies and establish consistent rules for data sharing, intellectual property and ethics, Khachaturian said in a telephone interview.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration hasn’t cleared new drugs for memory loss conditions in a decade. Approved medicines such as Eisai Co. (4523)’s Aricept ease symptoms without slowing or curing dementia.

Useful Lessons

A joint U.S.-European Union task force in 2011 found that all disease-modifying treatments for Alzheimer’s in the previous decade failed late-stage trials “despite enormous financial and scientific efforts.” Since then, at least four more experimental treatments have failed.

Eric Karran, director of research at the charity Alzheimer’s Research UK, who wasn’t among the signatories to the statement, said that failed trials can provide useful lessons. One of the four medicines, Eli Lilly & Co. (LLY)’s solanezumab, is undergoing further tests to determine if it helps people with mild Alzheimer’s disease, Karran said.

“If we could just get efficacy in one approach, we will unlock so much else, we will get so much more understanding,” Karran said at a press conference on Dec. 4. “If solanezumab is shown to work in mild Alzheimer’s disease, the pathway will be to take that earlier and earlier.”

Healthways…

http://www.healthways.com || http://www.healthways.com.au

Christian Sellars from MSD put on a terrific dinner in Crows Nest, inviting a group of interesting people to come meet with his team, with no agenda:

- Dr Paul Nicolarakis, former advisor to the Health Minister

- Dr Linda Swan, CEO Healthways

- Ian Corless, Business Development & Program Manager, Wentwest

- Dr Kevin Cheng, Project Lead Diabetes Care Project

- Dr Stephen Barnett, GP & University of Wollongong

- Warren Brooks, Customer Centricity Lead

- Brendan Price, Pricing Manager

- Wayne Sparks, I.T. Director

- Greg Lyubomirsky, Director, New Commercial Initiatives

- Christian Sellars, Director, Access

MSD are doing interesting things in health. In Christian’s words, they are trying to uncouple their future from pills.

After some chair swapping, I managed to sit across from Linda Swan from Healthways. It was terrific. She’s a Stephen Leeder disciple, spent time at MSD, would have been an actuary if she didn’t do medicine, and has been on a search that sounds similar to mine.

Healthways do data-driven, full-body, full-community wellness.

They’re getting $100M multi-years contracts from PHIs.

Amazingly, they’ve incorporated social determinants of health into their framework.

And even more amazingly, they’ve been given Iowa to make healthier.

They terraform communities – the whole lot.

Linda believes their most powerful intervention is a 20min evidence-based phone questionnaire administered to patients on returning home, similar to what Shane Solomon was rolling out at the HKHA. But they also supplant junk food sponsorship of sport and lobby for improvements to footpaths etc.

Just terrific. We’re catching up for coffee in January.

BMJ: Can behavioural economics make us healthy

- BE policies are by design less coercive and more effective than traditional approaches

- It is generally far more effective to punish than to reward

- Sticks masquerading as carrots – simultaneous, zero-sum incentives and penalties

- References to policies which have and have not worked – but why can’t policy be research?

- Conventional economics can therefore justify regulatory interventions, such as targeted taxes and subsidies, only in situations in which an individual’s actions imposes costs on others—for example, second hand cigarette smoke. But the potential reach of behavioural economics is much greater. By recognising the prevalence of less than perfectly rational behaviour, behavioural economics points to a large category of situations in which policy intervention might be justified—those characterised by costs which people impose on themselves (internalities), such as the long term health consequences of smoking on smokers.

- Is it fair to say that in a universal health care system, any preventable ill health imposes costs on others, as it is the tax payer who picks up the cost of treatment?

- present bias: the tendancy for decision makers tend to put too much weight on costs and benefits that are immediate and too little on those that are delayed. Present bias can be used to positive effect by providing small, frequent (i.e. immediate) payments for beneficial behaviours e.g. smoking cessation, medication adherence, weight loss

- “peanuts effect” decision error: the tendency to pay too little attention to the small but cumulative consequences of repeated decisions, such as the effect on weightof repeated consumption of sugared beverages or the cumulative health effect of smoking.

- competition and peer support are more powerful forms of behaviourally mediated interventions

Care of Nicholas Gruen.

PDF: CanBehaviouralEconomicsMakeUsHealthier_BMJ

Similarly in Health Affairs: http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/32/4/661.short

New Yorker post; Weight loss drugs

- not convinced this isn’t part of some pharma-sponsored PR campaign

- reference to research indicating gastric bypass may be mediated via changes in flora more than changes in gastric physiology

DECEMBER 4, 2013

DIET DRUGS WORK: WHY WON’T DOCTORS PRESCRIBE THEM?

The woman sat on my exam table and pointed to her snug paper gown. “Doctor,” she said, “I need your help losing weight.”

I spent the next several minutes speaking with her about diet and exercise, the health risks of obesity, and the benefits of weight loss—a talk I’ve been having with my patients for more than twenty years. But, like the majority of Americans, most of my patients remain overweight.

Afterward, I realized that what my patient wanted was a pill that would make her lose weight. I could have prescribed her one of four drugs currently approved by the F.D.A.: two, phentermine and orlistat, that have been around for more than a decade, and two others, Belviq (lorcaserin) and Qsymia (a combination of phentermine and topiramate), that have recently come onto the market and are the first ever approved for long-term use. (Ian Parker wrote about the F.D.A.’s approval process for new medications in this week’s issue.) The drugs work by suppressing appetite, by increasing metabolism, and by other mechanisms that are not yet fully understood. These new drugs, along with beloranib—which produces more dramatic weight loss than anything currently available but is still undergoing clinical trials—were discussed with great excitement last month by experts and researchers at the international Obesity Week conference in Atlanta.

But I’ve never prescribed diet drugs, and few doctors in my primary-care practice have, either. Donna Ryan, an obesity specialist at the Pennington Biomedical Research Center at Louisiana State University, has found that only a small percentage of the doctors she has surveyed regularly prescribe any of the drugs currently approved by the F.D.A. Sales figures indicate that physicians haven’t embraced the new medications, Qsymia and Belviq, either.

The inauspicious history of diet drugs no doubt contributes to doctors’ reluctance to prescribe them. In the nineteen-forties, when doctors began prescribing amphetamines for weight loss,rates of addiction soared. Then, in the nineties, fen-phen, a popular combination of fenfluramine and phentermine, was pulled from the market when patients developed serious heart defects. Current medications are much safer, but they produce only modest weight loss, in the range of about five to ten per cent, and they do have side effects.

Still, as Ryan pointed out, doctors aren’t always shy about prescribing medications that cause side effects and yield undramatic results. A five to ten per cent weight loss might not thrill patients, or even nudge them out of being overweight or obese, but it can improve diabetes control, blood pressure, cholesterol, sleep apnea, and other complications of obesity. And, although the drugs aren’t covered by Medicare or most states’ Medicaid programs, private insurance coverage of weight-loss drugs has improved and is likely to expand further under theAffordable Care Act, which requires insurers to pay for obesity treatment. So what prevents physicians from prescribing these drugs?

Several leading experts and researchers attending Obesity Week told me that the problem is that, while specialists who study obesity view it as a chronic but treatable disease, primary-care physicians are not fully convinced that they should be treating obesity at all. Even thoughphysicians since Hippocrates have known that excess body fat can cause diseases, the American Medical Association announced that it would recognize obesity itself as a disease only a few months ago. These divergent views on obesity represent one of the widest gulfs of understanding between generalists and specialists in all of medicine.

Lee M. Kaplan, co-director of the Weight Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, thinks that some bias comes from the average physician’s lack of appreciation for the complex physiology of weight homeostasis. Humans have evolved to avoid starvation rather than obesity, and we defend our body mass through an elaborate system involving the brain, the gut, fat cells, and a network of hormones and neurotransmitters, only a fraction of which have been identified. Obesity, Kaplan said, which represents dysfunction of this system, is likely not one disease but dozens.

That one person’s obesity is not like another’s may explain why some people lose a lot of weight with surgery, or a particular diet or drug, and some don’t. Kaplan thinks that if more doctors understood this, they’d view obesity treatment more receptively and realistically. He said, “If I were to say to you, ‘I have this drug that treats cancer,’ and you asked me, ‘What kind of cancer?,’ and I said, ‘All cancers,’ you’d laugh, because you recognize intuitively that cancer is a heterogeneous group of disorders. We’re going to look back on obesity one day and say the same thing.”

Obesity is potentially, in part, a neurological disease. Jeffrey Flier, an endocrinologist and dean of Harvard Medical School, has shown, like others, that repeatedly eating more calories than you burn can damage the hypothalamus, an area of the brain involved in eating and satiety. In other words, Big Gulps, Cinnabons, and Whoppers have altered our brains such that many people—particularly those with a genetic predisposition to obesity—find fattening foods all but impossible to resist once they’ve eaten enough of them. Louis J. Aronne, director of the Comprehensive Weight Control Program at New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, explained to me, “With so much calorie-dense food available, the hypothalamic neurons get overloaded and the brain can’t tell how much body fat is already stored. The response is to try to store more fat. So there’s very strong scientific evidence that obesity is not about people lacking willpower.”

But this message has not found its way into society, where obese people are still often considered self-indulgent and lazy, and face widespread discrimination. Several obesity experts told me they’ve encountered doctors who confide that they just didn’t like fat people and don’t enjoy taking care of them. Even doctors who treat obese patients feel stigmatized: “diet doctor” is not a flattering term. Donna Ryan, who switched from oncology to obesity medicine many years ago, recalls her colleagues’ surprise. “I had respect,” she says. “I was treating leukemia!”

George Bray, also of the Pennington Biomedical Research Center, thinks that socioeconomic factors play into physicians’ lack of enthusiasm for treating obesity. Bray points to the work ofAdam Drewnowski at the University of Washington, who has shown that obesity is, disproportionately, a disease of poverty. Because of this association, many erroneously see obesity as more of a social condition than a medical one, a condition that simply requires people to try harder. Bray said, “If you believe that obesity would be cured if people just pushed themselves away from the table, then why do you want to prescribe drugs for this non-disease, this ‘moral issue’? I think that belief permeates a lot of the medical field.”

Obesity experts with whom I spoke tended to be more optimistic than other physicians about the possibility that obesity can be treated successfully and that the obesity epidemic will be curbed. They point to exciting new research—for example, the finding that an alteration in gut bacteria, rather than mechanical shrinking of the stomach or intestine, may be what causes weight loss after gastric bypass. This raises the possibility that the benefits of surgery might become available without the surgery itself. They also note that public-health efforts seem to be reducing childhood obesity, even in poor communities. But they remain concerned that despite such promising developments, many physicians still don’t see obesity the way they do: as a serious, often preventable disease that requires intensive and lifelong treatment with a combination of diet, exercise, behavioral modification, surgery, and, potentially, drugs.

Louis Aronne thinks this will change as more physicians enter the field of obesity medicine, the physiology of obesity is better understood, and more effective treatment options become available. He likens the current attitude toward obesity to the prevailing attitude toward mental illness years ago. Aronne remembers, during his medical training, seeing psychotic patients warehoused and sedated, treated as less than human. He predicts that, one day, “some doctors are going to look back at severely obese patients and say, ‘What the hell was I thinking when I didn’t do anything to help them? How wrong could I have been?’ ”

Patients like the woman who asked me to help her lose weight may not have to wait that long. Specialists are now developing programs to aid primary-care physicians in treating obesity more aggressively and effectively. But we’ll have to want to treat it: as Kaplan argues, “Whether you call it a disease or not is not so germane. The root problem is that whatever you call it, nobody’s taking it seriously enough.”

Suzanne Koven is a primary-care doctor at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston and writes the column “In Practice” at the Boston Globe.

Photograph by Patrick Allard/REA/Redux.

Economist Intelligence Unit – Rethinking Cardiovascular Disease Prevention

Source: http://www.economistinsights.com/healthcare/opinion/heart-darkness%E2%80%94fighting-cvd-all-mind

CVD prevention at population level, such as a “fat tax” or smoking ban, relies heavily on regulation. This is its greatest strength – it can compel healthy behaviour (or seat belt wearing) – but also its greatest potential weakness. It inevitably involves some degree of coercion, which runs the risk of paternalism.It need not involve regulation, however. The same human flaws that are exploited by the food industry to persuade us to buy certain items at the check-out can also be used to persuade us to act in the interests of our own health. The current UK government is attempting to turn psychological weakness into an advantage outside of the legislative framework.

Its Behavioural Insights Team, commonly referred to as the “nudge unit”, is designed to seek “intelligent ways” to support and enable people to make better choices, using insights from behavioural science and medicine instead of increased rulemaking. Many of these goals overlap with CVD prevention, from smoking cessation to encouraging kids to eat healthier foods and walk to school more often. Early successes have brought them to the attention of the Obama administration in the US.

Besides the difficulties of making positive lifestyle changes, non-adherence to treatment is another significant obstacle to effective CVD prevention. Even after suffering a CVD incident, some patients forget to take their medication; other patients opt not to complete a course of treatment for other reasons, ranging from concerns about costs, the inconvenience involved with travel, to feelings of despondency caused by depression and anxiety. At its most anodyne, individuals frequently stop taking drugs prescribed for prevention after they feel better and think themselves cured.

This is part of a much wider medical problem: in the rich world adherence to treatment for all diseases is around 50%. Recognising the commercial opportunities here, private enterprise is looking to play a greater role. Earlier this year a US company called WellDoc launched a smartphone product aimed at giving type 2 diabetics better management of their treatment, through tailoured advice and motivational coaching. In the UK, meanwhile, a start-up calledImpact Health is developing a similar health psychology smartphone product to increase adherence to treatment among sufferers of Crohn’s disease.

CVD patients stand to benefit from such development in medical technology, although they may have to wait a little while yet. Impact Health’s online platform requires patients to have a smartphone. For this reason the start-up is targeting Crohn’s first and not CVD. As David Knull, one of its directors, explains, the profile of the average sufferer is generally around 30 years old—far younger than the average CVD patient, and much more likely to have a smartphone.

Report source: http://www.economistinsights.com/healthcare/analysis/heart-matter

Report PDF: The heart of the matter – Rethinking prevention of cardiovascular disease

The heart of the matter: Rethinking prevention of cardiovascular disease is an Economist Intelligence Unit report, sponsored by AstraZeneca. It investigates the health challenges posed by cardiovascular disease (CVD) in the developed and the developing world, and examines the need for a fresh look at prevention.

The report is also available to download in German, French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese (Brazilian) and Mandarin—see the Multimedia tab

Why read this report

- Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the world’s leading killer. It accounted for 30% of deaths around the globe in 2010 at an estimated total economic cost of over US$850bn

- The common feature of the disease across the world is its disproportionate impact on individuals from lower socio-economic groups

- Prevention could greatly reduce the spread of CVD: reduced smoking rates, improved diets and other primary prevention efforts are responsible for at least half of the reduction in CVD in developed countries in recent decades…

- …but prevention is little used. Governments devote only a small proportion of health spending to prevention of diseases of any kind—typically 3% in developed countries

- Population-wide measures like smoking bans and “fat taxes” yield significant results but require political adeptness to succeed. There is no shortcut for the slow work of changing hearts and minds

- The size of the CVD epidemic is such that a doctor-centred health system will not be able to cope. Innovative ways for nurses and non-medical personnel to provide preventative services are needed

- A growing number of stakeholders are involved in CVD prevention, sharing the burden with governments. Now, greater collaboration across different sectors and interest groups should be encouraged

- Collaboration works when incentives of stakeholders are aligned, including business. Finland’s famed North Karelia project suggests better alignment of interests is crucial to a successful “multi-sectoral” approach

Cardiovascular disease is the dominant epidemic of the 21st century. Dr Srinath Reddy, president of the World Heart Federation

We know a lot about what needs to be done, it just doesn’t get done. Beatriz Champagne, executive director of the InterAmerican Heart Foundation

Action at the country level will decide the future of the cardiovascular epidemic. Dr Shanthi Mendis, director ad interim, management of non-communicable diseases, WHO

Living on the edge with Farzad

- It’s not as simple as you give people information and they change their behavior. It’s information tools that build on that data and build on communities and a much more sophisticated understanding about how behavior changes. What TEDMED is also great at, is understanding the power of marketing. People think of marketing of being about advertising, but marketing is the best knowledge we have about how to change behavior and all those intangibles, those predictably irrational insights, of how and why we do what we do.

- It’s harnessing those, instead of having them lead to worse health – like present value discounting that leads to people wanting to procrastinate and eat that doughnut now instead of going to the gym. Or the power of anchoring, where we fixate on the first thing we see and won’t think objectively about the true risks of things. Or the herd effect, our friend is overweight and so we are more likely to be overweight.

- All those nudges that are possible can be delivered to us ubiquitously and continuously, and we can choose to have them. It’s not some big brother dystopic vision. It’s me saying, ‘I want to be healthier, so I will do something now that will help me overcome and use my irrationality to help me stay healthy. To me, that’s the neat new edge between mobile cloud computing, personal healthcare, behavioral economics, healthcare IT, data science and visualization, design, and marketing. It’s that sphere that has so many possibilities to get us to better health.

http://blog.tedmed.com/?p=4153

The exit interview: Farzad Mostashari on imagination, building healthcare bridges and his biggest “aha” moments

Farzad Mostashari, MD, stepped down from his post as the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), during the first week of October, which was also the first week of the Federal partial shutdown. During his tenure, Dr. Mostashari, who spoke at TEDMED 2011 with Aneesh Chopra, led the creation and definition of meaningful use incentives and tenaciously challenged health care leaders and patients to leverage data in ways to encourage partnerships with patients within the clinical health care team.

Farzad Mostashari, MD, stepped down from his post as the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), during the first week of October, which was also the first week of the Federal partial shutdown. During his tenure, Dr. Mostashari, who spoke at TEDMED 2011 with Aneesh Chopra, led the creation and definition of meaningful use incentives and tenaciously challenged health care leaders and patients to leverage data in ways to encourage partnerships with patients within the clinical health care team.

Whitney Zatzkin and Stacy Lu had the opportunity to speak with Dr. Mostashari during his last week in office.

WZ: Sometimes, a person will experience an “aha!” moment – a snapshot or event that reveals a new opportunity and challenges him/her to pursue something nontraditional. Was there a critical turning point when you figured out, ‘I’m the guy who should be doing this?’

Yeah, I’ve been fortunate to have a couple of those ‘aha’ moments in my life. One of them was when I was an epidemic intelligence service officer back in 1998, working for the CDC in New York City. I’ve always been interested in edge issues, border issues; things that are on the boundaries between different fields. I was there in public health, but I was interested in what was happening in the rest of the world around electronic transactions and using data in a more agile way.

In disease surveillance we often look back — the way we do claims data now – years later or months later you get the reports and you look for the outbreak, and often times the outbreak’s already come and gone by the time you pick it up. But I started thinking and imagining: What if the second something happens, you can start monitoring it? In New York City the fire department was monitoring ambulance calls. I said, ‘Wow, if we could just categorize those by the type of call, maybe we’ll see some sort of signal in the noise there.’

When I was first able to visualize the trends in the proportion of ambulance dispatches in NYC that were due to respiratory distress, what I saw was flu. What jumped out at me was the sinusoidal curve. Wham! At different times of year, it could be a stutter process – it would go up and you would see this huge increase, followed two weeks later by an increase in deaths. It was like the sky opening up. The evidence was there all along, but I am the first human being on earth to see this. That was validation, for me, of the idea that electronic data opens up worlds. To bring that data to life, to be able to extract meaning from those zeros and ones — that’s life and death. That was my first ‘aha’ moment.

The second aha was after I joined New York City Department of Health, and I started a data shop to build our policy around smoking and tracking chronic diseases. What we realized was that healthcare was leaving lives on the table. There were a lot of lives we could save by doing basic stuff a third-year medical student should do, but we’re not doing it. Related to that – Tom Frieden had a great TEDMED talk about everybody counts.

I said, ‘I want to take six months off and do a sabbatical, and see if there’s anything to using electronic health records to provide those insights, not to save lives by city level, but on the 10 to the 3 level – the 1,000 patient practice. That started the whole journey. None of the vendors at the time had the vision we had, but we finally got someone to work with us and rolled this system out. We called some doctors some 23 times, and did all the work to get to the starting line. Finally, I took Tom on a field visit to see one of the first docs to get the program.

It was a very normal storefront in Harlem, and a nice physician, very caring, very typical. I asked her what she thought of the program. She said, ‘It’s ok. I’m still getting used to it.’ I said, ‘Did you ever look at the registry tab on the right, where you can make a list of your patients? She said no. I said, ok – how many of your elderly patients did you vaccinate for flu this year? She said, ‘I don’t know, about 80 to 85 percent. I’m pretty good at that.’ I said, ‘o.k., let’s run a query.’ And it was actually something like 22 percent. And she said – this was the aha moment – ‘That’s not right.’

That’s generally the feeling the docs have when they get a quality measure report from the health plan. But that’s population health management — the ability to see for the first time ever that everybody counts. And being able to then think about decision support and care protocols to reduce your defect rate. That was the validation that we’re on to something. Without the tools to do this, all the payment changes in the world can’t make healthcare accountable for cost and quality if you can’t see it.

WZ: Everyone has that moment in life when they’re considering all of their career options. As you were considering medical school, what else was on the table?

I actually didn’t think I was going to go to medical school. I was at the Harvard School of Public Health. I was interested in making an impact in public health. I grew up in Iran, and thought I would do international public health work. And then my dad got sick; he had a cardiac issue. The contrast between the immediacy of the laying on of hands of healthcare, and the somewhat abstractness of international public health — the distance, the remove — tipped me into saying, ‘You know, maybe I should go to medical school.’ I’ve been on that edge between healthcare and public health ever since, and always trying to drag the two closer to each other.

SL: Fast forward 20 years. You’re giving another talk at TEDMED. What’s the topic?

TEDMED and Jay Walker’s vision is more powerful in the futurescope, rather than in the retroscope. It’s more powerful to be where we are today and imagine a different future rather than look back and say, ‘Oh, yeah, we’ve done this.’ So what’s the future I would love to imagine?

The most exciting thing – as Jay Walker once mentioned in a talk comparing “medspeed” to “techspeed” – is to fully imagine what will happen if techspeed is brought to healthcare. Right now, there’s all this unrealized value that’s being given away for free that doesn’t show up on any GDP lists – what Tim O’Reilly called “the clothesline paradox.” That kind of possibility brought to medicine, but where software costs $100,000 as opposed to free, and it evolves daily and is more powerful and quicker every day, and it’s beautiful and usable and intuitive, and that’s what people compete on.

And all of that is toward the goal of empowering people. Someone said, maybe it was Jay at TEDMED, that a 14-year-old kid in Africa with a smart phone has more access to information than Bill Clinton did as President. Information is power, and it has changed everything but healthcare. For me the vision is breaking down that wall, so that patients can be empowered and can bind themselves to the mast to use what we’ve learned about how behavior changes.

It’s not as simple as you give people information and they change their behavior. It’s information tools that build on that data and build on communities and a much more sophisticated understanding about how behavior changes. What TEDMED is also great at, is understanding the power of marketing. People think of marketing of being about advertising, but marketing is the best knowledge we have about how to change behavior and all those intangibles, those predictably irrational insights, of how and why we do what we do.

It’s harnessing those, instead of having them lead to worse health – like present value discounting that leads to people wanting to procrastinate and eat that doughnut now instead of going to the gym. Or the power of anchoring, where we fixate on the first thing we see and won’t think objectively about the true risks of things. Or the herd effect, our friend is overweight and so we are more likely to be overweight.

All those nudges that are possible can be delivered to us ubiquitously and continuously, and we can choose to have them. It’s not some big brother dystopic vision. It’s me saying, ‘I want to be healthier, so I will do something now that will help me overcome and use my irrationality to help me stay healthy. To me, that’s the neat new edge between mobile cloud computing, personal healthcare, behavioral economics, healthcare IT, data science and visualization, design, and marketing. It’s that sphere that has so many possibilities to get us to better health.

The thing about the health is, we have a Persian saying: Health is a crown on the head of the healthy that only the sick can see. When you have it, you don’t appreciate it, but when you’re sick and someone you love is sick, there’s nothing better. You would do anything to get that. We need to bring that vision of the crown to everyone and help each of us grab it when we can.

WZ: I noticed you closing your eyes while preparing to answer a question. How do you pursue being able to exercise your imagination, in particular while you’re sitting in a building that’s been marked for being the least imaginative?

Because the world, as it is, is too immediate and real and limiting, sometimes you have to close your eyes to see a different world.

What has been amazing has been to see that, contrary to what people expect, this building is filled with people with untapped, unbound, unfettered imaginations who are slogging through. They’re just trapped. You give them the opening, the smallest bit of daylight to exercise that, and they’re off and running.

I give a lot of credit to Todd Park as our “innovation fellow zero,” He saw the possibility that there are more than two kinds of people in the world, innovators and everybody else. For him, it was about going to create a space where outside innovators can be the catalyst or spark that elevates and permissions the innovation of the career civil servant at CMS in Baltimore. That’s been cool.

SL: What’s your bowtie going to do after you leave HHS? Will we see it lounging on the beach in Boca?

I like the bowtie. I think I’m going to keep it. Perhaps the @FarzadsBowtie Twitter handle is going to go into hibernation, I don’t know. I don’t control it. One of the things the bowtie does for me is help me remember not to get too comfortable.

I once said at the Consumer Health IT Summit – ‘You’re a bunch of misfits – glorious misfits. And I feel like I’m very well suited to be your leader. You know, I always felt American in Iran, and felt Iranian in America when I came here. I felt like a jock among my geeky friends, and like a geek among jocks. For crying out loud, I wear a bowtie! I don’t have to tell you I’m a misfit.’

It’s that sense of not fitting into the world as it is. The world doesn’t fit me. So instead of saying, ‘I need to change,’ this group of people said, ‘The world needs to change.’ That’s the difference between a misfit and a glorious misfit.

The person who doesn’t fit into our healthcare system is the patient. The patient’s preferences don’t fit into the need to maximize revenue and do more procedures. The patient’s family doesn’t fit into the, ‘I want to do an eight-minute visit and get you out the door’ agenda. The patient asking questions doesn’t fit. That’s the change we need to make. It’s not that we need to change. Healthcare needs to change to fit the patient.

Shortly following this interview, Dr. Mostashari left HHS and is now the a visiting fellow of the Engelberg Center for Health Care Reform at the Brookings Institution, where he aims to help clinicians improve care and patient health through health IT, focusing on small practices.

This interview was edited for length and readability.

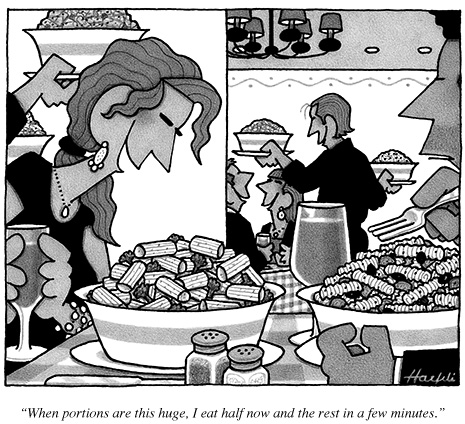

When portions are this huge, I eat half now and then the rest in a few minutes

I have no idea, I just write…

Punchy interview with Bill Gates’ favourite author. Alignment on food. Other things interesting, but unrelated.

http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2013/11/vaclav-smil-wired/?mbid=synd_gfdn_bgtw

This Is the Man Bill Gates Thinks You Absolutely Should Be Reading

- BY CLIVE THOMPSON

- 11.25.13

- 6:30 AM

Author Vaclav Smil tackles the big problems facing America and the world. Andreas Laszlo Konrath“There is no author whose books I look forward to more than Vaclav Smil,” Bill Gates wrote this summer. That’s quite an endorsement—and it gave a jolt of fame to Smil, a professor emeritus of environment and geography at the University of Manitoba. In a world of specialized intellectuals, Smil is an ambitious and astonishing polymath who swings for fences. His nearly three dozen books have analyzed the world’s biggest challenges—the future of energy, food production, and manufacturing—with nuance and detail. They’re among the most data-heavy books you’ll find, with a remarkable way of framing basic facts. (Sample nugget: Humans will consume 17 percent of what the biosphere produces this year.)His conclusions are often bleak. He argues, for instance, that the demise of US manufacturing dooms the country not just intellectually but creatively, because innovation is tied to the process of making things. (And, unfortunately, he has the figures to back that up.) WIRED got Smil’s take on the problems facing America and the world.

Author Vaclav Smil tackles the big problems facing America and the world. Andreas Laszlo Konrath“There is no author whose books I look forward to more than Vaclav Smil,” Bill Gates wrote this summer. That’s quite an endorsement—and it gave a jolt of fame to Smil, a professor emeritus of environment and geography at the University of Manitoba. In a world of specialized intellectuals, Smil is an ambitious and astonishing polymath who swings for fences. His nearly three dozen books have analyzed the world’s biggest challenges—the future of energy, food production, and manufacturing—with nuance and detail. They’re among the most data-heavy books you’ll find, with a remarkable way of framing basic facts. (Sample nugget: Humans will consume 17 percent of what the biosphere produces this year.)His conclusions are often bleak. He argues, for instance, that the demise of US manufacturing dooms the country not just intellectually but creatively, because innovation is tied to the process of making things. (And, unfortunately, he has the figures to back that up.) WIRED got Smil’s take on the problems facing America and the world.

You’ve written over 30 books and published three this year alone. How do you do it?

Hemingway knew the secret. I mean, he was a lush and a bad man in many ways, but he knew the secret. You get up and, first thing in the morning, you do your 500 words. Do it every day and you’ve got a book in eight or nine months.

What draws you to such big, all-encompassing subjects?

I saw how the university life goes, both in Europe and then in the US. I was at Penn State, and I was just aghast, because everyone was what I call drillers of deeper wells. These academics sit at the bottom of a deep well and they look up and see a sliver of the sky. They know everything about that little sliver of sky and nothing else. I scan all my horizons.

Let’s talk about manufacturing. You say a country that stops doing mass manufacturing falls apart. Why?

In every society, manufacturing builds the lower middle class. If you give up manufacturing, you end up with haves and have-nots and you get social polarization. The whole lower middle class sinks.

You also say that manufacturing is crucial to innovation.

Most innovation is not done by research institutes and national laboratories. It comes from manufacturing—from companies that want to extend their product reach, improve their costs, increase their returns. What’s very important is in-house research. Innovation usually arises from somebody taking a product already in production and making it better: better glass, better aluminum, a better chip. Innovation always starts with a product.

Look at LCD screens. Most of the advances are coming from big industrial conglomerates in Korea like Samsung or LG. The only good thing in the US is Gorilla Glass, because it’s Corning, and Corning spends $700 million a year on research.

American companies do still innovate, though. They just outsource the manufacturing. What’s wrong with that?

Look at the crown jewel of Boeing now, the 787 Dreamliner. The plane had so many problems—it was like three years late. And why? Because large parts of it were subcontracted around the world. The 787 is not a plane made in the USA; it’s a plane assembled in the USA. They subcontracted composite materials to Italians and batteries to the Japanese, and the batteries started to burn in-flight. The quality control is not there.

Bill Gates’ actual bookshelf. We count six books by Smil in this section alone. Ian Allen

Bill Gates’ actual bookshelf. We count six books by Smil in this section alone. Ian Allen

Can IT jobs replace the lost manufacturing jobs?

No, of course not. These are totally fungible jobs. You could hire people in Russia or Malaysia—and that’s what companies are doing.

Restoring manufacturing would mean training Americans again to build things.

Only two countries have done this well: Germany and Switzerland. They’ve both maintained strong manufacturing sectors and they share a key thing: Kids go into apprentice programs at age 14 or 15. You spend a few years, depending on the skill, and you can make BMWs. And because you started young and learned from the older people, your products can’t be matched in quality. This is where it all starts.

You claim Apple could assemble the iPhone in the US and still make a huge profit.

It’s no secret! Apple has tremendous profit margins. They could easily do everything at home. The iPhone isn’t manufactured in China—it’s assembled in China from parts made in the US, Germany, Japan, Malaysia, South Korea, and so on. The cost there isn’t labor. But laborers must be sufficiently dedicated and skilled to sit on their ass for eight hours and solder little pieces together so they fit perfectly.

But Apple is supposed to be a giant innovator.

Apple! Boy, what a story. No taxes paid, everything made abroad—yet everyone worships them. This new iPhone, there’s nothing new in it. Just a golden color. What the hell, right? When people start playing with color, you know they’re played out.

Let’s talk about energy. You say alternative energy can’t scale. Is there no role for renewables?

I like renewables, but they move slowly. There’s an inherent inertia, a slowness in energy transitions. It would be easier if we were still consuming 66,615 kilowatt-hours per capita, as in 1950. But in 1950 few people had air-conditioning. We’re a society that demands electricity 24/7. This is very difficult with sun and wind.

Look at Germany, where they heavily subsidize renewable energy. When there’s no wind or sun, they boost up their old coal-fired power plants. The result: Germany has massively increased coal imports from the US, and German greenhouse gas emissions have been increasing, from 917 million metric tons in 2011 to 931 million in 2012, because they’re burning American coal. It’s totally zany!

What about nuclear?

The Chinese are building it, the Indians are building it, the Russians have some intention to build. But as you know, the US is not. The last big power plant was ordered in 1974. Germany is out, Italy has vowed never to build one, and even France is delaying new construction. Is it a nice thought that the future of nuclear energy is now in the hands of North Korea, Pakistan, India, and Iran? It’s a depressing thought, isn’t it?

The basic problem was that we rushed into nuclear power. We took Hyman Rickover’s reactor for submarines and pushed it so America would beat Russia. And that’s just the wrong reactor. It was done too fast with too little forethought.

You call this Moore’s curse—the idea that if we’re innovative enough, everything can have yearly efficiency gains.

It’s a categorical mistake. You just cannot increase the efficiency of power plants like that. You have your combustion machines—the best one in the lab now is about 40 percent efficient. In the field they’re about 15 or 20 percent efficient. Well, you can’t quintuple it, because that would be 100 percent efficient. Impossible, right? There are limits. It’s not a microchip.

The same thing is true in agriculture. You cannot increase the efficiency of photosynthesis. We improve the performance of farms by irrigating them and fertilizing them to provide all these nutrients. But we cannot keep on doubling the yield every two years. Moore’s law doesn’t apply to plants.

So what’s left? Making products more energy-efficient?

Innovation is making products more energy-efficient — but then we consume so many more products that there’s been no absolute dematerialization of anything. We still consume more steel, more aluminum, more glass, and so on. As long as we’re on this endless material cycle, this merry-go-round, well, technical innovation cannot keep pace.

Yikes. So all we’ve got left is reducing consumption. But who’s going to do that?

My wife and I did. We downscaled our house. It took me two years to find a subdivision where they’d let me build a custom house smaller than 2,000 square feet. And I’ll test you: What is the simplest way to make your house super-efficient?

Insulation!

Right. I have 50 percent more insulation in my walls. It adds very little to the cost. And you insulate your basement from the outside—I have about 20 inches of Styrofoam on the outside of that concrete wall. We were the first people building on our cul-de-sac, so I saw all the other houses after us—much bigger, 3,500 square feet. None of them were built properly. I pay in a year for electricity what they pay in January. You can have a super-efficient house; you can have a super-efficient car, a little Honda Civic, 40 miles per gallon.

Your other big subject is food. You’re a pretty grim thinker, but this is your most optimistic area. You actually think we can feed a planet of 10 billion people—if we eat less meat and waste less food.

We pour all this energy into growing corn and soybeans, and then we put all that into rearing animals while feeding them antibiotics. And then we throw away 40 percent of the food we produce.

Meat eaters don’t like me because I call for moderation, and vegetarians don’t like me because I say there’s nothing wrong with eating meat. It’s part of our evolutionary heritage! Meat has helped to make us what we are. Meat helps to make our big brains. The problem is with eating 200 pounds of meat per capita per year. Eating hamburgers every day. And steak.

You know, you take some chicken breast, cut it up into little cubes, and make a Chinese stew—three people can eat one chicken breast. When you cut meat into little pieces, as they do in India, China, and Malaysia, all you need to eat is maybe like 40 pounds a year.

So finally, some good news from you!

Except for antibiotic resistance, which is terrible. Some countries that grow lots of pork, like Denmark and the Netherlands, are either eliminating antibiotics or reducing them. We have to do that. Otherwise we’ll create such antibiotic resistance, it will be just terrible.

So the answers are not technological but political: better economic policies, better education, better trade policies.

Right. Today, as you know, everything is “innovation.” We have problems, and people are looking for fairy-tale solutions—innovation like manna from heaven falling on the Israelites and saving them from the desert. It’s like, “Let’s not reform the education system, the tax system. Let’s not improve our dysfunctional government. Just wait for this innovation manna from a little group of people in Silicon Valley, preferably of Indian origin.”

You people at WIRED—you’re the guilty ones! You support these people, you write about them, you elevate them onto the cover! You really messed it up. I tell you, you pushed this on the American public, right? And people believe it now.

Bill Gates reads you a lot. Who are you writing for?

I have no idea. I just write.

nutrition and exercise, not dieting…

Plenty of sensible lines, though nothing about fasting…

http://bigthink.com/experts-corner/why-dieting-is-the-worst-way-to-lose-weight

Why Dieting is the Worst Way to Lose Weight

by TOM VENUTO NOVEMBER 23, 2013, 6:00 AM

Dieting is the worst way to lose weight. Most people would say I’m crazy for making such an outrageous claim. However, by the time you finish reading this short article, I think you’ll agree with me: Not only that, my hope is that you’ll agree so much that you’ll join me on my mission against “dieting” — at least the way the multi-billion dollar weight loss industry has been pushing it on everyone for years.

So what on Earth am I talking about, “dissing” dieting like that? Haven’t I said it myself many times before that diet is the most important factor for burning fat and keeping it off? Actually, no. That’s where the misunderstanding is. What I’ve said is that if I were to put the many elements of successful fat loss into the order of their priority, nutrition would be at the top of the list.

There’s a big difference between “diet” and “nutrition”

You may see where I’m going with this now, but you also might be wondering if this is just semantics. Yes, it is. But that’s precisely why “diet” and “nutrition” are not saying the same thing. Words are loaded with meaning between the lines. Being successful is about understanding the power of words — and using the words that successful people use.

Few words are more semantically loaded than diet. Think about what connotations — and whether they are positive or negative. What comes up when you think of diet?

Restriction

Forbidden foods

Banned food groups

What you can “never eat”

Hunger

Gimmicks

Fads/trends (that pass or come and go in cycles)

Quick fixes (often unhealthy or dangerous)

The word “diet” was supposed to simply describe the way a person eats. “Diet” comes from the Latin, diaeta, meaning “way of life.” But in our technologically advanced, sedentary society today, and with the obesity crisis we’re facing, and the multi-billion dollar industry it has spawned, the word “diet” has become tainted . . .

Today, I think ‘diet’ carries too much negative baggage to use so loosely. The way I define it, a diet is any unsustainable change in your eating behavior to try to lose weight. When you say you’re going on a diet, you’re also saying that at some point you’re going off it. While you’re on it, you suffer all those negative associations I mentioned above.

By contrast, think about the connotations of the word nutrition. Do you think of anything negative? I don’t. I think of:

Vitamins

Minerals

Micronutrients

Fiber

Muscle-building protein (amino acids)

Unrefined foods, closer to their form in nature

Energy

Vitality

Health

Now think of the word program. A program implies that there is structure. So I define a nutrition program as a structured plan you can follow as a lifestyle, which nourishes you with nutritious food that helps you get leaner, stronger, fitter and healthier . . . and stay that way.

I propose we replace “diet” with “nutrition program” unless we are specifically talking about something short term.

I believe this distinction in words is crucial, but just to play devil’s advocate, let’s assume that diet and nutrition program mean exactly the same thing. There’s still a huge problem with the diet alone approach, and therefore, why 99% of the entire weight loss industry is wrong:

Diet is only one of the elements needed for a leaner, stronger, fitter, and healthier body. There are three other elements that most people are missing.

Dieting might improve your health. On the other hand, depending on your approach to “diet,” it might destroy your health. Dieting is not always healthy. Nutrition and training together is a sure-fire pathway to health.

Weight loss diets fail 80-95% of the time. Not because they don’t take the weight off, but because they rarely keep it off. Most dieters relapse. Drug addicts and alcoholics in rehab have a higher success rate than that.

Exercise and an active lifestyle are vital for long term weight loss maintenance.

The right kind of exercise is also vital for re-shaping your body . . .

Weight Loss Versus Body Transformation

There’s a world of difference between losing weight and transforming your body.

Dieting can’t transform your body. Only training can do that.

Dieting can’t make you stronger. Only training can do that.

Dieting can’t make you fitter. Only training can do that.

With diets, you might fit into smaller clothes. But you also may become a smaller version of your old self… a skinny fat person . . . weighing less . . . but still flabby (and weak).

The Muscle Loss Epidemic

With diet alone, 30 to 50% of your weight loss could come from lean body mass. And if you’re getting older, the prospect of losing muscle and strength should genuinely frighten you.

After age 50, you lose 1-2% of your lean muscle every year if you do nothing (if you’re not resistance training). After age 60, you lose up to 3% per year.

Let’s suppose you’re 50 or 60 and you’re thinking, “A few percent of my lean mass? What’s the big deal? I have no desire to look muscly.” I can understand that. Your goals and values do change as you get older. But I already realize that most people don’t want to look like bodybuilders. However, gaining lean muscle, strength and fitness will improve the quality of anyone’s life.

Maintaining the muscle you have must be a priority for everyone because losing lean mass every year means losing your mobility and losing your independence as you get older.

Stop the Diet Insanity!

Given these facts, it’s sheer insanity that we have millions of people who want to lose weight — for health and for happiness — and the first thing or only thing they think of as a solution is DIET. They’re asking for deprivation, hunger, missing out on favorite foods, loss of muscle, loss of strength and eventually, loss of independence, putting a burden on other people to take care of them.

I’m not being melodramatic. I’m on mission to expose the mistakes of the dieting mentality and promote the benefits of the muscle-building, fitness and nutrition lifestyle.

The good news is, there’s a right way to burn fat and transform your body, but it’s not a one-trick show. You have to put several pieces together. This is total lifestyle change, so it’s not easy. But it is worth it.

This is as near to a miracle formula as you will ever find. It’s the 4 elements of the Burn the Fat, Feed the Muscle approach:

Nutrition program

Resistance (strength) training

Cardio Training

Mental training

Dieting is the worst way to lose weight

Not only that, here’s the nail in the coffin for 99% of what the weight loss industry is telling you: weight loss is the wrong goal to begin with. Burning the fat and keeping the muscle is the right goal. Even better, the right goal is to get leaner, stronger, fitter and healthier.

Train hard, and expect success.

© 2013 Tom Venuto, author of Burn the Fat, Feed the Muscle: Transform Your Body Forever Using the Secrets of the Leanest People in the World

Author Bio

Tom Venuto is a fat-loss expert, transformation coach and bestselling author of Burn the Fat, Feed the Muscle. Tom holds a degree in exercise science and has worked in the fitness industry since 1989, including fourteen years as a personal trainer. He promotes natural, healthy strategies for burning fat and building muscle, and as a lifetime steroid-free bodybuilder, he’s been there and done it himself. Tom blends the latest science with a realistic, commonsense approach to transforming your body and maintaining your perfect weight for life.

For more information please visit http://www.burnthefatblog.com/ and http://www.burnthefatfeedthemuscle.com/ and follow the author on Facebook and Twitter