http://blogs.crikey.com.au/croakey/2014/12/01/as-nutritionists-enable-health-washing-by-coca-cola-a-call-to-end-unhealthy-sponsorship/

As nutritionists enable health-washing by Coca-Cola, a call to end unhealthy sponsorship

It’s a question the Nutrition Society of Australia and its members might be pondering, after having Coca-Cola as a gold sponsor of their recent annual scientific meeting.

As the World Cancer Congress in Melbourne this week puts the spotlight on the implications of rising obesity rates for cancer, health advocate Todd Harper highlights the contribution of soft drinks to obesity, and argues that health organisations need to look for healthier funding sources.

***

Todd Harper, CEO of Cancer Council Victoria, writes:

No sporting club or health event would accept sponsorship from a tobacco company in Australia today, even if it was allowed.

We know that smoking kills, and so do everything possible to reduce its visibility to ensure younger people aren’t encouraged to take up the habit.

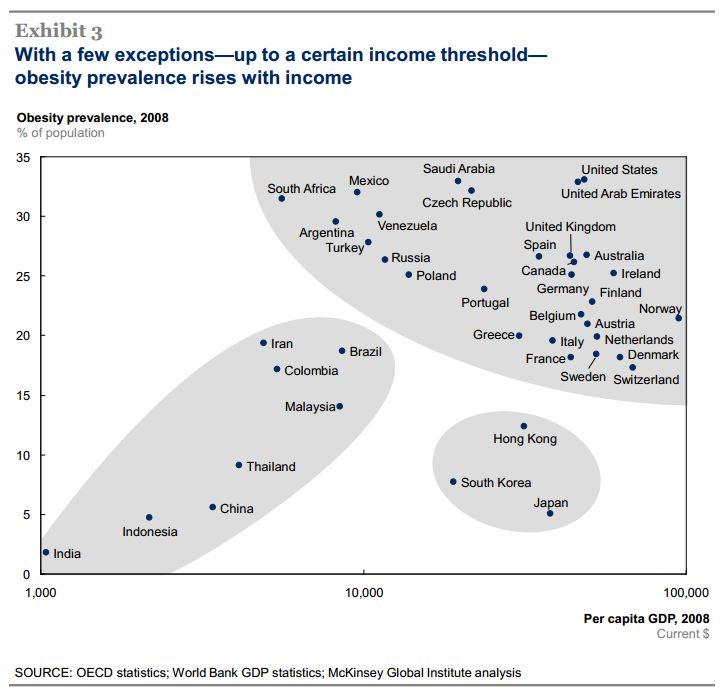

Obesity is also a known risk factor for many cancers, as well as other chronic diseases, yet organisations and events continue to accept sponsorship from the very companies peddling products that contribute to this significant health issue.

Despite this, some organisations focused on health, and particularly healthy kids, see little problem in holding their hands out for money from soft drink companies.

Our recent Cancer in Victoria: Statistics and Trends 2013 report revealed uterine cancer rates are steadily rising; a cancer for which obesity is a principal risk factor. Obesity is also a risk factor for breast, bowel, oesophageal, pancreas, uterine, kidney, gallbladder and thyroid cancers.

In fact, we recently learned from the World Health Organization (WHO) that nearly half a million new cancer cases around the world can be attributed to high Body Mass Index each year – including more than 7000 in Australia. (A new study by the International Agency for Research on Cancer found that nearly half a million new cancer cases per year can be attributed to high body mass index (BMI). The study was published on November 26 in The Lancet Oncology. Using its methodology, more than 7000 new cancer cases in Australia per year can be attributed to high BMI.)

The number of Victorians diagnosed with cancer is projected to double by 2024-2028 to more than 41,000 cases a year, with obesity considered a significant contributor to this. It’s a problem that we can’t ignore.

Many people are aware of the dangers of smoking, and the link between smoking and cancer – which is why we’ve seen such a rapid decline in smoking rates. At the same time we are seeing an equally rapid rise in the number of people who are overweight or obese. We need the same awareness about this as a risk factor if we are to stop more cancers before they start.

Drinking soft drinks contributes to higher kilojoule intake, weight gain and obesity. With one can of Coke containing 10 teaspoons of sugar, each can consumed increases the risk of being overweight.

The WHO recommends the consumption of sugary drinks should be restricted, as do Australia’s recently reviewed dietary guidelines, while the World Cancer Research Fund recommends consumption should be avoided entirely. Leaders in cancer control are meeting in Melbourne this week for the World Cancer Congress, and the challenges related to rising global obesity will be firmly on the agenda.

In the meantime, Coca-Cola continues to sugar-coat its image; fooling the community into believing it is part of the solution to the obesity epidemic.

Rather than being part of the solution like it claims, this multi-billion dollar company is trying to veil the impact of its products by positioning itself as a promoter of physical activity. This is merely a distraction from the fact that it continues to promote its sugary drinks as being part of a healthy diet.

Disturbingly, the company has aligned itself with organisations that encourage healthy active lifestyles, such as the Bicycle Network.

The decision by Bicycle Network to enter into a partnership with Coca-Cola attracted strong criticism from public health experts after a piece in Croakey a year ago, yet the partnership continues. This is especially problematic considering the ‘Happiness’ program is targeting teenagers, a group particularly susceptible to marketing and the highest consumers of these drinks.

Similarly, the Nutrition Society of Australia, the peak scientific nutrition group in the country, has Coca-Cola as a gold sponsor for its Annual Scientific Meeting underway in Tasmania.

Similarly, the Nutrition Society of Australia, the peak scientific nutrition group in the country, has Coca-Cola as a gold sponsor for its Annual Scientific Meeting underway in Tasmania.

This is disappointing on a number of levels, not least of all the fact that one of the themes for the conference is ‘Diet and cancer: what does the evidence show?’

Coca-Cola’s attempts to link itself with these organisations won’t reduce the consumption of sugary beverages and won’t make a gram of difference in reducing overweight and obesity.

Wouldn’t it be better to create alternative sponsorship sources for health-promoting organisations?

As was done with the banning of tobacco sponsorship and the creation of alternative funding sources through VicHealth, it’s time for some similarly creative thinking.

Creative thinking that will kick Coca-Cola out of sponsoring health-promoting activities, and create healthier options for organisations like the Nutrition Society and Bicycle Network.

My fear is that unless we take such action, we run the risk of limiting the impact of important health programs such as the Rethink Sugary Drinkcampaign, encouraging a switch to water and reduced-fat milk; and theLiveLighter campaign, which aims to help people make simple lifestyle choices to improve their overall health and cut their cancer risk.

These programs are vital yet are minnows in the campaign to win the healthy hearts and minds of the public when faced with the corporate might of the highly processed food and drink companies, but with some creative thinking and political will, the scales can be tipped in favour of a healthier way.

• Todd Harper is CEO of Cancer Council Victoria.