Excellent summary of current US funding situation…

http://www.vox.com/2014/9/10/6121631/the-pay-less-get-more-era-of-health-care

The “pay less, get more” era of health care

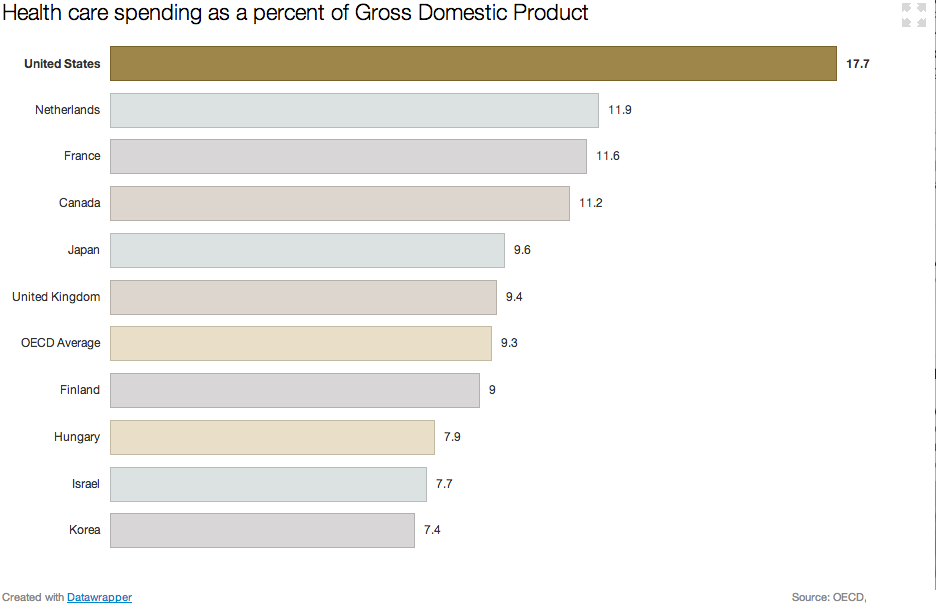

Health care spending has, for decades, followed a consistent pattern. America pays more and more for health care — and gets less and less.

Between 1990 and 2012, the insured rate in the United States fell two percentage points, from 86.6 to 84.6 percent. If the insured rate had just held steady, six million more people would have been covered in 2012.

While we were covering less people, we kept spending more on health care. National health spending, over that time period, rose from 12 percent of the economy in 1990 to 17.2 percent in 2012. Adjusted for inflation, health-care spending rose from $1.1 trillion to $2.8 trillion over those 22 years.

/cdn3.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/692516/Data_plot.0.png)

That’s been the typical story of American health care: a lousy deal where we get less and spend more.

But there’s a growing body of evidence that this trend is changing; that we’re starting to get a shockingly better deal in a way that has giant consequences for how America spends money. Call it the “get more, pay less” era.

The “get more, pay less” era of health care spending

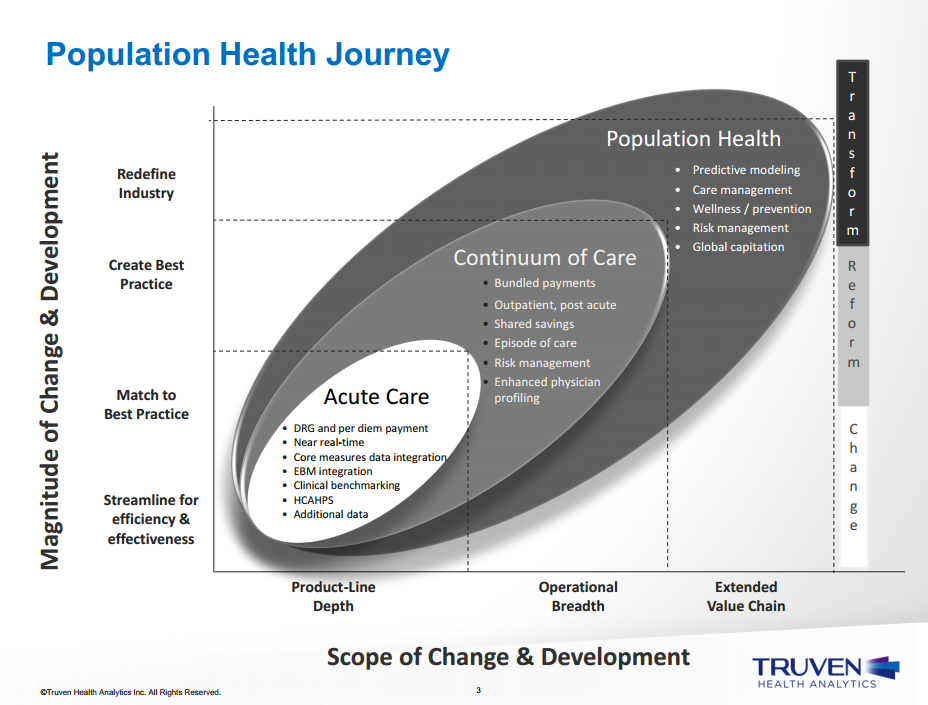

There are two big trends that, taken together, suggest we may be fundamentally different era of health care spending.

The first is lots more people getting coverage. This is mostly Obamacare: the health care law is expected to expand insurance coverage to 26 million people by 2024. In 2014 alone, most estimates suggest about 5 million people have gained health coverage through the law. The recovering economy is likely playing a supporting role, too, with those gaining jobs also gaining access to employer-sponsored coverage.

The second big trend is in what we spend: actuaries expect that health care costs will grow slower over the next decade than they did in the 1990s and 2000s.

More specifically: health care costs grew, on average, 2 percent faster than the economy between 1990 and 2008. Health spending took over an ever-growing share of the economy. Workers barely got raises; skyrocketing premiums ate up most of their additional wages.

The next decade is now expected to be different. Actuaries at the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services project health care costs to grow 1 percent faster than the rest of the economy between 2013 and 2023.

“We are seeing historic moderation in costs now over a considerable period of time,” Kaiser Family Foundation president Drew Altman says. HIs group recently released data showing slow growth of employer-sponsored coverage. “It’s absolutely true we’re seeing that and any expert will tell you that.”

This is startling: over the next decade, forecasters think our health spending will grow at a slower rate, even as millions and millions of Americans gain access to health insurance. After two decades of spending more and getting less, we’re entering an era of spending less and getting more. It’s bizarro health spending world.

There are signs of this throughout the health care system

One thing that’s so striking about the “get more, pay less” trend is that it isn’t limited to one particular insurance plan or program. It’s starting to crop up in lots of new health care data, suggesting this change has become pervasive in the health care industry.

Start with private health insurance: the Kaiser Family Foundation recently published research finding the average price of Obamacare’s benchmark will fall slightly in 2015. As my colleague Ezra Klein wrote recently, this just about unprecedented. “Falling is not a word that people associate with health-insurance premiums,” he writes .”They tend to rise as regularly as the morning sun.”

Lower premiums make health care dollars stretch further: Obamacare shoppers will be able to buy the coverage they had last year at a slightly lower price. That’s a big deal when you’re talking about paying for a health insurance program meant to cover tens of millions of Americans.

Increasingly narrow health insurance networks are another sign of “get more, pay less” era. Over the past few years — and especially under Obamacare —insurers have gravitated towards cheaper premium plans to offer access to a smaller number of doctors.

These plans’ more limited doctor choice can have a big impact on spending. Research from economists Jon Gruber and Robin McKnight found that, in one example, switching enrollees to these plans cut overall spending by one third. And while patients had access to fewer hospitals, the hospitals that were in network were of equally good quality.

Then there’s the Medicare side of the equation, where there has been a unprecedented decline in per person spending. Margot Sanger-Katz at the Upshot has had two fantastic posts on Medicare’s cost slowdown. One of them points out the fact that, since 2010, per patient spending has grown slower than the rest of the economy. You can see that in this graph, which charts “excess cost growth” in Medicare (health wonk speak for cost growth above and beyond inflation). For the past few years, excess growth has been replaced by slower-than-the-economy growth.

As Sanger-Katz points out, there are two trends at play in Medicare. One is that younger baby boomers keep aging onto the program. They’re younger than Medicare’s really old patients, and typically less expensive to care for. That drives down per person spending for the whole population.

But there’s something else going on that looks to be a more permanent trend: Medicare patients are using less expensive care. They go to the doctor more, and the hospital less. You can see this in new data from the Medicare Trustees’ report, which shows per person spending on Medicare Part A (the program that covers inpatient care) falling over the past few years.

/cdn2.vox-cdn.com/assets/4826288/medicare_per_person.png)

Because of this shift away from hospital care, Medicare Part A now spends less money to cover more people. It paid $266.8 billion covering 50.3 million people in 2012. In 2013, the the same program spent $266.2 billion to cover 51.9 million people.

Will “pay less, get more” health care stick?

We have had periods of relatively slow health care growth before. In the mid-1990s, for example, there was a stretch of time when health spending grew at the same rate as the rest of the economy. You can see that in this graph.

/cdn2.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/679852/helath_growth.0.png)

Most health economists attribute that to the rise of health maintenance organizations, or HMOs, that sharply limited access to specialists. Patients, unsurprisingly, didn’t like those limitations and there was a backlash. HMOs declined and health spending rose again.

But some health economists say that this time feels different. For one, the changes are happening in private insurance and Medicare, suggesting there’s no single — and thus easily reversible — force driving the change.

And while there are more patients in narrow network products, something akin to HMOs, consumers are often choosing to be there. These are shoppers on the Obamacare exchanges who have decided to make a trade off: they’re take lower premiums for less choice of doctor.

“In the 1990s, people were essentially stuck in HMOs,” M.I.T economist Gruber says. “This time, people are given an option and make a choice. That’s why I’m more confident this slower growth will stick.”

Medicare actuaries are not fortune tellers; they do not have a crystal ball that conjures up the future of health care with perfect clarity. But at least at this particular moment, there are lots of signs cropping up to suggest something very important in health care is changing, and it’s for the better.