Terrific Daniel Katz piece on LinkedIn on the actual causes of death.

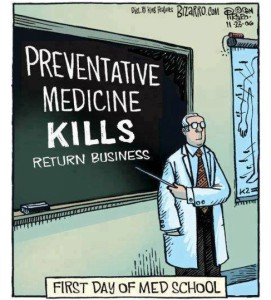

Heart disease, cancer, stroke and diabetes are not causes, they are diseases.

The 1993 JAMA article “Actual Causes of Death” lays it out, and the top three causes of premature death, which account for 80% of the risk, are:

- tobacco

- diet

- exercise

Population-based research published in 2009 showed that people who ate well, exercise routinely, avoided tobacco, and controlled their weight had an 80% lower probability across their entire life span of developing ANY major chronic disease- heart disease, cancer, stroke, diabetes, dementia, etc.- than those who smoked, ate badly, didn’t exercise, and lost control of their weight

http://www.linkedin.com/today/post/article/20131110133420-23027997-what-really-kills-us

What REALLY Kills Us

Heart disease is not the leading cause of death among men and women in the United States. Cancer, stroke, pulmonary disease, diabetes, and dementia are not the other leading causes of early mortality and/or chronic malady either.

Don’t get me wrong- these are the very diseases immediately responsible for an enormous loss of years from life, and an even greater loss of life from years. In that context, heart disease is indeed the most common immediate precipitant of early death among women and men alike. Cancer, stroke, and diabetes do indeed follow close behind. It’s just that these diseases aren’t really causes. They are effects.

We got this message loud, clear, and first- at least in the modern era- in what really should have been a culture-changing research paper published in JAMA in 1993 entitled ‘Actual Causes of Death in the United States.’ In that analysis, two leading epidemiologists, Drs. William Foege and J. Michael McGinnis, looked into the factors that accounted for the chronic diseases and other insults that immediately preceded premature deaths. When they were done crunching numbers, they had a list of ten factors that accounted for almost all of the premature deaths in our country every year.

Let’s digress to note we cannot ‘prevent’ death. But what makes death tragic is not that it happens- we are all mortal- but that it happens too soon. And even worse, that it happens after a long period of illness drains away vitality, capacity, and the pleasure of living. Chronic disease can produce a long, lingering twilight of quasi-living, before adding to that injury the insult of a premature death. And that, we can prevent. We can preserve vitality, and we can postpone death to its rightful time, at the end of our full life expectancy.

Now back to our regularly scheduled program. There were two astounding things about McGinnis and Foege’s list of ten factors*. First, we as individuals have substantial control over everything on the list, and virtually complete control over most of the entries. Second, just the first three factors on the list – tobacco, diet, and physical activity – accounted for fully 80% of the action. In other words, the actual, underlying “cause” of premature death in our country fully 8 times in 10 comes down to bad use of our feet (lack of physical activity), our forks (poor dietary choices), and/or our fingers (holding cigarettes).

I trust you immediately see the up-side to this. If bad use of feet, forks, and fingers accounts for 80% of premature deaths (and a bounty of chronic disease), it stands to reason that optimal use of feet, forks, and fingers could eliminate up to 80% of all premature mortality and chronic illness. This proves to be exactly true. Feet, forks, and fingers are the master levers of medical destiny.

We know this not just from McGinnis and Foege’s seminal paper, but from a steady drumbeat of corroborating research spanning the two decades since. Scientists at the CDC replicated the findings in the original paper in an update a decade later. Population-based research published in 2009 showed that people who ate well, exercise routinely, avoided tobacco, and controlled their weight had an 80% lower probability across their entire life span of developing ANY major chronic disease- heart disease, cancer, stroke, diabetes, dementia, etc.- than those who smoked, ate badly, didn’t exercise, and lost control of their weight. Flip the switch on any of these factors from bad to good, and the lifetime risk of serious chronic disease was reduced by nearly 50%. But firing on all four cylinders produced a greater net benefit than perhaps any advance in the history of medicine. These very findings have been replicated again, and again– and have been shown to extend that same influence over the expression of our very genes. DNA is not destiny, and to a substantial extent- dinner is. By changing what we eat and how we live, we can alter the expression of our very genes in a way that immunizes us against chronic disease occurrence, recurrence, or progression.

And so it is we have the knowledge to eliminate fully 80% of all chronic disease and premature death. The contention isn’t even controversial.

But knowledge, alas, isn’t power unless it is put to use. And for the most part, we have not leveraged the astounding memo we first got in 1993. Not only have we failed to slash rates of chronic disease, we are actually seeing them rise- with onset at ever-younger ages. We could bequeath to our children a world in which 8 times in 10, heart attacks and strokes and cancer simply don’t happen. Instead, should current trends persist, we will bequeath to them a world in which they and their peers succumb to just such preventable calamities more often and earlier than we.

So current trends cannot persist- and that, bluntly, is why I wrote Disease Proof. As a society, we clearly know the ‘what,’ but as individuals and families; spouses and siblings; parents and grandparents- most of us, just as clearly, don’t know how. How, despite the challenges of modern living, do we adopt, maintain, and enjoy a healthful diet? How, despite those same challenges, do we fit fitness in? How do we navigate around other challenges, from sleep deprivation and lack of energy, to overwhelming stress, to chronic pain?

These questions have answers, and I know them. I know them not because I’m special, but because it’s my job to know them. Pilots know how to fly planes; nuclear physicists know how to split atoms. I am a health expert, and I know how to get to health and weight control from here. Like any worthwhile thing, it requires a skill set- but we are used to that. We had to learn how to read and ride our bikes. We had to learn how to drive our cars and use our smart phones. Every worthwhile undertaking in our lives has involved someone who already knew how teaching us. Our job was to learn, and apply.

Health and weight control are exactly the same. In Disease Proof, I share the full skill set I apply myself.

We could, as a culture, eliminate 80% of all chronic disease. But my family and yours cannot afford to keep on waitin’ on the world to change. By taking matters into our own hands, we can lose weight and find health right now. We can reduce our personal risk of chronic disease, and that of the people we love, by that very same 80%. We can make our lives not just longer, but better.

What really kills us prematurely, and all too often imposes years of misery before hand, isn’t a list of chronic diseases, but the factors that cause those diseases. What really takes years from life and life from years is a willingness to know WHAT, yet neglect the opportunity to know HOW. What really kills us is the failure to turn what we know and have long known, into what we do. We can change that, and substantially disease-proof ourselves and those we love, any time we’re ready. I hope that’s now, because waiting- is really killing us.

-fin

DISEASE PROOF is available in bookstores nationwide and at:

Dr. David L. Katz; www.davidkatzmd.com

www.turnthetidefoundation.org

http://www.facebook.com/pages/Dr-David-L-Katz/114690721876253

http://twitter.com/DrDavidKatz

http://www.linkedin.com/pub/david-l-katz-md-mph/7/866/479/

*the list is: tobacco, diet and activity patterns, alcohol, microbial agents, toxic agents, firearms, sexual behavior, motor vehicles, and illicit use of drugs