Category Archives: policy

Thanks CT.

This is bang on. Good to see some good people agreeing. I don’t feel nearly as mad.

http://www.afr.com/Page/Uuid/1fec72e4-07d2-11e4-a983-9084720e3436

Melbourne forum aims for politics-free economic thought

PUBLISHED: 8 HOURS 13 MINUTES AGO | UPDATE: 2 HOURS 3 MINUTES AGO

The discussion of necessary reforms is dominated by special pleading by vested interests. Photo: Gabriele Charotte

ROSS GARNAUT AND PETER DAWKINS

Australia needs rigorous, independent economic policy debate and analysis to inform economic policy. The Melbourne Economic Forum seeks to contribute to meeting that need by bringing to account the considerable analytic capacity in economics based in the city.

A joint endeavour of the University of Melbourne and Victoria University, this new forum will bring together 40 leading economists, from or with institutional connections to Melbourne to discuss the great economic policy issues confronting Australia and the world.

The forum is independent of vested interests and partisan political connections. It will not support the position of any political party or campaign of any group. It will focus on analysis of policy in the public interest. Almost any policy proposal has implications for the distribution of incomes and wealth and income amongst Australians. Our objective will be to make these implications explicit and to point out their implications for wider conceptions of the public interest.

It would be surprising if high quality analysis of policy choice for Australia does not, from time to time, earn the criticism of participants from all corners of the political contest and from many groups with vested interests in particular uses of public resources and government power. The test of the forum’s value will be its success in illuminating the consequences of policy choice and not its immediate and direct influence on government decisions.

Through the final four decades of last century, dispassionate economic analysis and debate played a major role in illuminating government decisions on economic policy. Rational economic analysis became more important in underpinning serious discussion of policy choice. It emerged from interaction of economists in some of the universities with the predecessor to the Productivity Commission, the national media and later the public service and some parts of the political community. This interaction gradually built support for an open, competitive economy. The ideas preceded their influence, but eventually were of large importance in guiding the reform era under the Hawke, Keating and Howard governments. The resulting reform era laid the foundations for 23 years of economic growth without recession.

CHANGE IS A NECESSITY

Business organisations and the trade union movement joined the consensus and joined the discussion in constructive ways. The Business Council of Australia was formed to develop policy positions that were in the national economic interest, though not necessarily in the commercial interests of every one of its members.

Both rational economic analysis in the public interest and Australia’s high standard of living have been weakened by developments in the early twenty first century and are now under threat.

As mineral prices fall, productivity growth languishes and our population ages, Australia needs a new program of economic reform. Yet the discussion of necessary reforms is dominated by special pleading by vested interests.

Of course there is room for disagreement about the size of the challenge Australia faces if it is to maintain high levels of employment and prosperity. And different policy prescriptions will have different consequences for the distribution of the burden of adjustment to a more sombre economic outlook. A lazy policy response would shift the burden onto the shoulders of those Australians who lose their jobs or cannot find one.

Yet a budget that is viewed by the community as unfair is inimical to the task of building a consensus for reform.

The Melbourne Economic Forum will contribute to these debates, starting with a session on the economic outlook for Australia and the impacts of alternative policy responses. In September we will take on the international policy challenges most pertinent to the G20 meeting in Australia later in the year.

In November, we will venture into the hazardous territory of tax system reform and federal-state financial relations.

Bi-monthly forums in 2015 will tackle issues such as infrastructure, investment, foreign investment and trade policy.

Reviving the tradition of rigorous, independent policy thinking is not a hankering for the past but an essential precondition for a new wave of economic reform to secure employment growth and rising prosperity for all Australians in a far more challenging global economic environment.

Professor Ross Garnaut is professor of economics at the University of Melbourne. Professor Peter Dawkins is vice-chancellor at Victoria University. For more details on the Melbourne Economic Forum see melbourneeconomicforum.com.au.

The Australian Financial Review

Why Good People Do Bad Things

People don’t commit fraud because they are greedy, but because they are nice…

Audio:

http://www.npr.org/2012/05/01/151764534/psychology-of-fraud-why-good-people-do-bad-things

Enron, Worldcom, Bernie Madoff, the subprime mortgage crisis.

Over the past decade or so, news stories about unethical behavior have been a regular feature on TV, a long, discouraging parade of misdeeds marching across our screens. And in the face of these scandals, psychologists and economists have been slowly reworking how they think about the cause of unethical behavior.

In general, when we think about bad behavior, we think about it being tied to character: Bad people do bad things. But that model, researchers say, is profoundly inadequate.

Which brings us to the story of Toby Groves.

Chapter 1

Toby grew up on a farm in Ohio. As a kid, the idea that he was a person of strong moral character was very important to him. Then one Sunday in 1986, when Toby was around 20, he went home for a visit with his family, and he had an experience that made the need to be good dramatically more pressing.

Toby Groves origin story.

Twenty-two years after Toby made that promise to his father, he found himself standing in front of the exact same judge who had sentenced his brother, being sentenced for the exact same crime: fraud.

And not just any fraud — a massive bank fraud involving millions of dollars that drove several companies out of business and resulted in the loss of about a hundred jobs.

In 2008, Toby went to prison, where he says he spent two years staring at a ceiling, trying to understand what had happened.

Was he a bad character? Was it genetic? “Those were things that haunted me every second of every day,” Toby says. “I just couldn’t grasp it.”

This very basic question — what causes unethical behavior? — has been getting a fair amount of attention from researchers recently, particularly those interested in how our brains process information when we make decisions.

And what these these researchers have concluded is that most of us are capable of behaving in profoundly unethical ways. And not only are we capable of it — without realizing it, we do it all the time.

Chapter 2

Consider the case of Toby Groves.

In the early 1990s, a couple of years after graduating from college, Toby decided to start his own mortgage loan company — and that promise to his father was on his mind.

2a

So Toby decided to lie.

He told the bank that he was making $350,000, when in reality he was making nowhere near that.

This is the first lie Toby told — the unethical act that opened the door to all the other unethical acts. So, what was going on in his head at the time?

“There wasn’t much of a thought process,” he says. “I felt like, at that point, that was a small price to pay and almost like a cost of doing business. You know, things are going to happen, and I just needed to do whatever I needed to do to fix that. It wasn’t like … I didn’t think that I was going to be losing money forever or anything like that.”

Consider that for a moment.

Here is a man who stood with his heartbroken father and pledged to behave ethically. Anyone involved in the mortgage business knows that it is both unethical and illegal to lie on a mortgage application.

How could that promise be so easily broken?

The Promise Flashback 2Chapter 3

To understand, says Ann Tenbrunsel, a researcher at Notre Dame who studies unethical behavior, you have to consider what this looks like from Toby’s perspective.

There is, she says, a common misperception that at moments like this, when people face an ethical decision, they clearly understand the choice that they are making.

“We assume that they can see the ethics and are consciously choosing not to behave ethically,” Tenbrunsel says.

This, generally speaking, is the basis of our disapproval: They knew. They chose to do wrong.

But Tenbrunsel says that we are frequently blind to the ethics of a situation.

Over the past couple of decades, psychologists have documented many different ways that our minds fail to see what is directly in front of us. They’ve come up with a concept called “bounded ethicality”: That’s the notion that cognitively, our ability to behave ethically is seriously limited, because we don’t always see the ethical big picture.

One small example: the way a decision is framed. “The way that a decision is presented to me,” says Tenbrunsel, “very much changes the way in which I view that decision, and then eventually, the decision it is that I reach.”

Essentially, Tenbrunsel argues, certain cognitive frames make us blind to the fact that we are confronting an ethical problem at all.

Tenbrunsel told us about a recent experiment that illustrates the problem. She got together two groups of people and told one to think about a business decision. The other group was instructed to think about an ethical decision. Those asked to consider a business decision generated one mental checklist; those asked to think of an ethical decision generated a different mental checklist.

Tenbrunsel next had her subjects do an unrelated task to distract them. Then she presented them with an opportunity to cheat.

Those cognitively primed to think about business behaved radically different from those who were not — no matter who they were, or what their moral upbringing had been.

“If you’re thinking about a business decision, you are significantly more likely to lie than if you were thinking from an ethical frame,” Tenbrunsel says.

According to Tenbrunsel, the business frame cognitively activates one set of goals — to be competent, to be successful; the ethics frame triggers other goals. And once you’re in, say, a business frame, you become really focused on meeting those goals, and other goals can completely fade from view.

4b

Tenbrunsel listened to Toby’s story, and she argues that one way to understand Toby’s initial choice to lie on his loan application is to consider the cognitive frame he was using.

“His sole focus was on making the best business decision,” she says, which made him blind to the ethics.

Obviously we’ll never know what was actually going through Toby’s mind, and the point of raising this possibility is not to excuse Toby’s bad behavior, but simply to demonstrate in a small way the very uncomfortable argument that these researchers are making:

That people can be genuinely unaware that they’re making a profoundly unethical decision.

It’s not that they’re evil — it’s that they don’t see.

And if we want to attack fraud, we have to understand that a lot of fraud is unintentional.

Chapter 4

Tenbrunsel’s argument that we are often blind to the ethical dimensions of a situation might explain part of Toby’s story, his first unethical act. But a bigger puzzle remains: How did Toby’s fraud spread? How did a lie on a mortgage application balloon into a $7 million fraud?

According to Toby, in the weeks after his initial lie, he discovered more losses at his company — huge losses. Toby had already mortgaged his house. He didn’t have any more money, but he needed to save his business.

The easiest way for him to cover the mounting losses, he reasoned, was to get more loans. So Toby decided to do something that is much harder to understand than lying on a mortgage application: He took out a series of entirely false loans — loans on houses that didn’t exist.

Creating false loans is not an easy process. You have to manufacture from thin air borrowers and homes and the paperwork to go with them.

Toby was CEO of his company, but this was outside of his skill set. He needed help — people on his staff who knew how loan documents should look and how to fake them.

And so, one by one, Toby says, he pulled employees into a room.

3a

“Maybe that was the most shocking thing,” Toby says. “Everyone said, ‘OK, we’re in trouble, we need to solve this. I’ll help you. You know, I’ll try to have that for you tomorrow.’ ”

According to Toby, no one said no.

Most of the people who helped Toby would not talk to us because they didn’t want to expose themselves to legal repercussions.

Of the four people at his company Toby told us about, we were able to speak about the fraud with only one — a woman on staff named Monique McDowell. She was involved in fabricating documents, and her description of what happened and how it happened completely conforms to Toby’s description.

If you accept what they’re saying as true, then that raises a troubling scenario, because we expect people to protest when they’re asked to do wrong. But Toby’s employees didn’t. What’s even more troubling is that according to Toby, it wasn’t just his employees: “I mean, we had to have assistance from other companies to pull this off,” he says.

To make it look like a real person closed on a real house, Toby needed a title company to sign off on the fake documents his staff had generated. And so after he got his staff onboard, Toby says he made some calls and basically made the same pitch he’d given his employees.

“It was, ‘Here is what happened. Here is the only way I know to fix it, and if you help me, great. If you won’t, I understand.’ Nobody said, ‘Maybe we’ll think about this. … Within a few minutes [it was], ‘Yes, I’ll help you.’ ”

So here we have people outside his company, agreeing to do things completely illegal and wrong.

Again, we contacted several of the title companies. No one would speak to us, but it’s clear from the legal cases that title companies were involved. One title company president ended up in jail because of his dealings with Toby; another agreed to a legal resolution.

So how could it be that easy?

Chapter 5

Typically when we hear about large frauds, we assume the perpetrators were driven by financial incentives. But psychologists and economists say financial incentives don’t fully explain it. They’re interested in another possible explanation: Human beings commit fraud because human beings like each other.

We like to help each other, especially people we identify with. And when we are helping people, we really don’t see what we are doing as unethical.

Lamar Pierce, an associate professor at Washington University in St. Louis, points to the case of emissions testers. Emissions testers are supposed to test whether or not your car is too polluting to stay on the road. If it is, they’re supposed to fail you. But in many cases, emissions testers lie.

“Somewhere between 20 percent and 50 percent of cars that should fail are passed — are illicitly passed,” Pierce says.

Financial incentives can explain some of that cheating. But Pierce and psychologist Francesca Gino of Harvard Business School say that doesn’t fully capture it.

They collected hundreds of thousands of records and were actually able to track the patterns of individual inspectors, carefully monitoring those they approved and those they denied. And here is what they found:

If you pull up in a fancy car — say, a BMW or Ferrari — and your car is polluting the air, you are likely to fail. But pull up in a Honda Civic, and you have a much better chance of passing.

cars

Why?

“We know from a lot of research that when we feel empathy towards others, we want to help them out,” says Gino.

Emissions testers — who make a modest salary — see a Civic and identify, they feel empathetic.

Essentially, Gino and Pierce are arguing that these testers commit fraud not because they are greedy, but because they are nice.

“And most people don’t see the harm in this,” says Pierce. “That is the problem.”

Pierce argues that cognitively, emissions testers can’t appreciate the consequences of their fraud, the costs of the decision that they are making in the moment. The cost is abstract: the global environment. They are literally being asked to weigh the costs to the global environment against the benefits of passing someone who is right there who needs help. We are not cognitively designed to do that.

“I’ve never talked to a mortgage broker who thought, ‘When I help someone get into a loan by falsifying their income, I deeply consider whether or not I would destabilize the world economy,’ ” says Pierce. “You are helping someone who is real.”

Gino and Pierce argue that Toby’s staff was faced with the same kind of decision: future abstract consequences, or help out the very real person in front of them.

And so without focusing on the ethics of what they were doing, they helped out a person who was not focusing on the ethics, either. And together they perpetrated a $7 million fraud.

Chapter 6

As for Toby, he says that maintaining the giant lie he’d created was exhausting day in and day out.

5a

So in 2006, when two FBI agents showed up at his office, he quickly confessed everything. He says he was relieved.

Two years later, he was standing in front of the same judge who had sentenced his brother. A short time after that, he was in jail, grateful that his father wasn’t alive to see him, wondering how he ended up where he did.

“The last thing in the world that I wanted to do in my life would be to break that promise to my father,” he says. “It haunts me.”

The Promise Flashback 1

Now if these psychologists and economists are right, if we are all capable of behaving profoundly unethically without realizing it, then our workplaces and regulations are poorly organized. They’re not designed to take into account the cognitively flawed human beings that we are. They don’t attempt to structure things around our weaknesses.

Some concrete proposals to do that are on the table. For example, we know that auditors develop relationships with clients after years of working together, and we know that those relationships can corrupt their audits without them even realizing it. So there is a proposal to force businesses to switch auditors every couple of years to address that problem.

Another suggestion: A sentence should be placed at the beginning of every business contract that explicitly says that lying on this contract is unethical and illegal, because that kind of statement would get people into the proper cognitive frame.

And there are other proposals, of course.

Or, we could just keep saying what we’ve always said — that right is right, and wrong is wrong, and people should know the difference.

Web story produced and edited by Maria Godoy; on-air story edited by Planet Money and Anne Gudenkauf

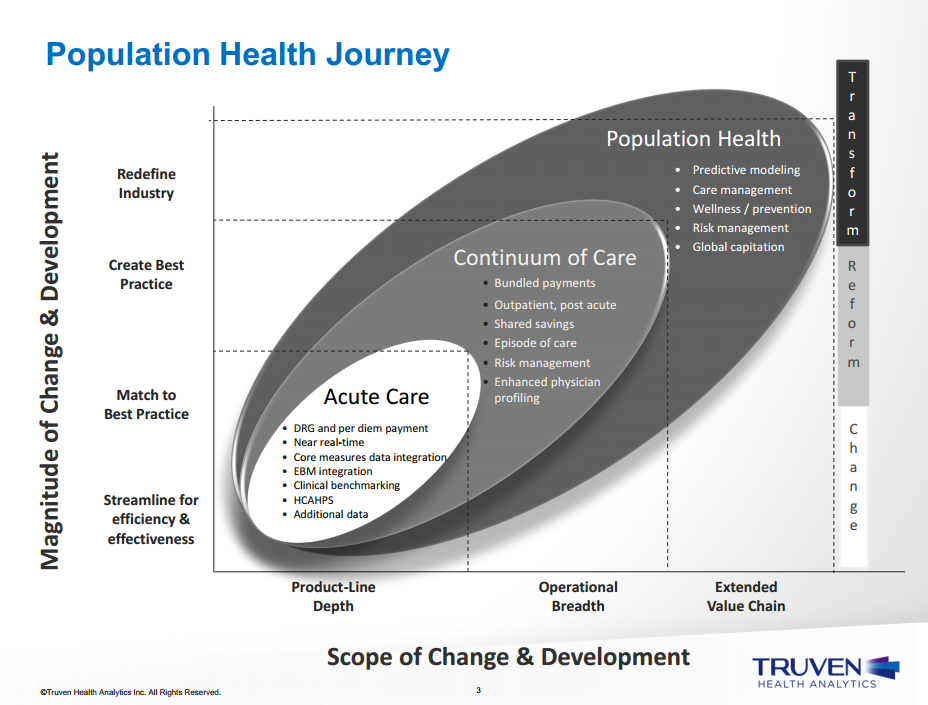

Population Health Journey

Missed the presentation, but caught the slide show… very cool, though still too doctor centric.

Doctors should not be involved in the delivery of population health because it’s not that hard…

Healthcare, meet capitalism – Jonathan Bush

The $2.7 trillion industry lacks accountability for exorbitant costs. The system incentivizes doctors (and hospitals) to do tests and procedures, instead of paying them to do their jobs—keeping people healthy. It’s like paying carpenters to use nails.

“The biggest lie that we baked into our thinking,” Bush said in Aspen, is that “starting in 1958, in the wake of World War II, the government wanted to control wage inflation, so they let employers provide healthcare as an incentive (What could go wrong? It’s 1958!)—was this idea that healthcare itself is just a monolithic, identical thing. That there’s no value in price shopping. That there’s no value in choosing whether or not to get [a certain health service]. We act, as a society, on the unconscious level, like we’re not in charge. This is a massive problem. Not just because we utilize expensive things, but because we give up the opportunity for those things to get better.”

http://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2014/07/a-case-against-donating-to-hospitals/373637/

Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pWBf7G2JH2M#t=1830

Healthcare, Meet Capitalism

Self-described “lunatic-fringe disruptors” depict U.S. healthcare like one of Ayn Rand’s dystopias. The $2.7 trillion industry lacks accountability for exorbitant costs. The system incentivizes doctors (and hospitals) to do tests and procedures, instead of paying them to do their jobs—keeping people healthy. It’s like paying carpenters to use nails.

“I believe we are on the cusp of an oil rush—a fabulous revolution of profit-making and cost-saving in health care,” disruptor Jonathan Bush told a rapt audience at the Aspen Ideas Festival last week. In the Rand comparison, Bush might be John Galt—were he not exuding as much benevolence as relentless capitalism. And he’s not giving up on the system; he’s trying to upend it.

Last week I moderated a discussion that became heated—by moderated-panel standards, and by no part of mine—between Bush, Toby Cosgrove (CEO of the Cleveland Clinic), Rushika Fernandopulle (CEO of Iora Health), and Dena Bravata (CMO of Castlight Health). It ended in an emphatic plea by Bush to never donate money to a hospital.

That was met with equal parts laughter and applause. From Cosgrove, seated three inches to his right, neither.

To Bush, CEO and co-founder of the $4.2 billion health-technology company Athena Health healthcare is a business, driven by markets like any other. Altruism and profit-driven business need not be at odds. It’s incomprehensible and unsustainable that people have no idea what their care costs and have no incentive to consider cheaper options.

“Profit is a dirty word among the corduroy-elbow crowd in the research hospitals and foundations,” Bush wrote in his recently-released book, Where Does It Hurt? “But just like any business, from Samsung to Dogfish Head Brewery, this industry will grow and innovate by figuring out what we need and want, and selling it to us at prices we’re willing and able to pay.”

In Aspen, Bush mentioned Invisalign braces and LASIK surgery as procedures that have been driven by the free market. These things started off exorbitantly expensive, but prices fell and fell. For LASIK, the procedure was “$2,800 per eye [in the 1990s]; now it’s $200 per eye, including a ride to and from the procedure.”

The oft-cited, disquieting numbers—the U.S. spends the largest percentage of its GDP on healthcare of any country (by far) but ranks 42nd in global life expectancy and similarly underwhelms in many other health metrics—are projected to worsen. Massive hospitals systems are buying out their competition across the country, charging exorbitant premiums without incentive to cut costs or optimize the care they provide. Bush’s gushing proposition is that when patients can “shop” for healthcare based on quality and price, it will drive innovation and better care. Innovation will inevitably disrupt the bloated status quo. But the current system has to be allowed to fail. That might sound bleak, but to innovators like Bush, Fernandopulle, and Bravata, it’s an opportunity for reinvention.

Forecasting of this sort is the currency of the Aspen conference (hosted by the Aspen Institute and The Atlantic), but Bush has the infectious passion that makes it feel like he’s one of those people who, while giving a keynote on the need for change, is already halfway out the door to make something happen.

Here’s the second half of the discussion, which neatly explains some fundamental problems with healthcare delivery:

Dena Bravata is the chief medical officer of Castlight, whose platform helps patients compare cost and quality to make informed healthcare decisions—shifting incentives for doctors toward lower-cost, higher-quality care.

Rushika Fernandopulle is a primary care physician and co-founder of a small company called Iora Health that is trying to fix healthcare from the bottom up.

“We start by changing the payment system,” Fernandopulle said, “which I think is part of the problem. Instead of getting paid fee-for-service, we blow that up and say we should get a fixed fee for what we do. That allows us to care for a population, and our job is to keep them healthy. If you believe that, you completely change the delivery model.”

Iora assigns each patient a personal health coach who does the blocking and tackling in dealing with the healthcare system. They interact by email and video chat, reaching out to patients instead of leaving the onus on the patient to follow up on their care. In Fernandopulle’s view, athena health, which is still contingent on the current fee-for-service model, is something of a dinosaur. Fernandopulle is a disruptor of disruptors.

Toby Cosgrove, the former surgeon and current CEO of one of the largest healthcare systems in the U.S., the Cleveland Clinic, cites redundancy: “What we need to understand is that not all hospitals can be all things to all people.” The Cleveland Clinic, for example, has become expert in cardiothoracic surgery, drawing patients from across the country. In Cosgrove’s model, there might be only one hospital in the country that does a certain complex procedure—but it does the procedure extremely well, efficiently, and on a scale that is maximally cost-effective. Drawing on his experience in Vietnam evacuating injured soldiers, Cosgrove argued for moving patients to expert physicians, rather than trying to have sub-sub-specialized experts everywhere.

So the future of U.S. healthcare will not come in the form of more hospitals. As Cosgrove noted, we already have plenty. Hospital occupancy in the U.S. right now is 65 percent. “Twenty years ago [the U.S.] had a million hospital beds, Cosgrove said. “There are now 800,000, and we still have too many.”

Bush recognizes that the core of healthcare is the relationship between the doctor and the patient. He says that any successful health-business model will be predicated on maximizing the act of total presence during a doctor visit. Ancillary staff will do the busy work that might keep a physician away from her patients. The doctor’s undivided attention is what patients want, and giving it is what makes a doctor’s job meaningful and effective. Despite demand from patients and doctors for more time together, Bush notes, the average visit is eight minutes.

When large hospital systems leverage their market position and brand names to overcharge for basic services, they not only subsidize research, but they perpetuate inefficiency. A cornered market favors complacency and maintenance of the status quo. In every other industry, if you’re still using a pager in 2014—as many doctors are—your business fails when your clients go to Iora Health, where they can video chat.

In his book, Bush calculated the fortune that could be made if a person wanted to start their own MRI business. At Massachusetts General Hospital, an MRI can be billed to an insured patient for $5,315. Bush proposes that an industrious person could rent an MRI machine for around $8,000 per month, a suburban park office for $1,000, two technicians for $6,500 each (including benefits), and around $3,000 for taxes and fees. That’s $25,000 per month in cost. If you can do three scans per hour and run twelve hours per day, you’d break even at $28 per MRI.

“The biggest lie that we baked into our thinking,” Bush said in Aspen, is that “starting in 1958, in the wake of World War II, the government wanted to control wage inflation, so they let employers provide healthcare as an incentive (What could go wrong? It’s 1958!)—was this idea that healthcare itself is just a monolithic, identical thing. That there’s no value in price shopping. That there’s no value in choosing whether or not to get [a certain health service]. We act, as a society, on the unconscious level, like we’re not in charge. This is a massive problem. Not just because we utilize expensive things, but because we give up the opportunity for those things to get better.”

Pincer funding: how to support appropriate coding of adverse events without rewarding bad behaviour

There’s a problem with correct coding of adverse events. In effect, we want a system that rewards correct coding, but punishes harmful behaviour.

If the institution is punished in any way for adverse events, they will be far less likely to code their occurrence.

If the institution is not punished (i.e. rewarded or unaffected) for adverse events, then adverse events will either continue or at best remain unchanged.

A thought bubble had today at the safety and quality commission workshop involves the idea of a pincer funding arrangement, specifically suited to Australia’s current funding arrangements.

At the local hospital district (or individual hospital) level, pay for coded adverse events, but then impose financial penalties at the state (or local hospital district) level.

I imagine they’d just all learn new ways to game this, but the intent is to reward correct coding, but punish harmful behaviour.

Crossing the creepy line – big data in health

Hospitals and insurers need to be mindful about crossing the “creepiness line” on how much to pry into their patients’ lives with big data.

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-06-26/hospitals-soon-see-donuts-to-cigarette-charges-for-health.html

Your Doctor Knows You’re Killing Yourself. The Data Brokers Told Her

You may soon get a call from your doctor if you’ve let your gym membership lapse, made a habit of picking up candy bars at the check-out counter or begin shopping at plus-sized stores.

That’s because some hospitals are starting to use detailed consumer data to create profiles on current and potential patients to identify those most likely to get sick, so the hospitals can intervene before they do.

Information compiled by data brokers from public records and credit card transactions can reveal where a person shops, the food they buy, and whether they smoke. The largest hospital chain in the Carolinas is plugging data for 2 million people into algorithms designed to identify high-risk patients, while Pennsylvania’s biggest system uses household and demographic data. Patients and their advocates, meanwhile, say they’re concerned that big data’s expansion into medical care will hurt the doctor-patient relationship and threaten privacy.

Related:

- Video: Can This Teen Cure Cancer With Big Data?

- Slideshow: 10 Ways Your Life Is Feeding the Big Data Beast

- Consumers Need Protection From Data Abuse

“It is one thing to have a number I can call if I have a problem or question, it is another thing to get unsolicited phone calls. I don’t like that,” said Jorjanne Murry, an accountant in Charlotte, North Carolina, who has Type 1 diabetes. “I think it is intrusive.”

Acxiom Corp. (ACXM) and LexisNexis are two of the largest data brokers who collect such information on individuals. Acxiom says their data is supposed to be used only for marketing, not for medical purposes or to be included in medical records. LexisNexis said it doesn’t sell consumer information to health insurers for the purposes of identifying patients at risk.

Bigger Picture

Much of the information on consumer spending may seem irrelevant for a hospital or doctor, but it can provide a bigger picture beyond the brief glimpse that doctors get during an office visit or through lab results, said Michael Dulin, chief clinical officer for analytics and outcomes at Carolinas HealthCare System.

Carolinas HealthCare System operates the largest group of medical centers in North Carolina andSouth Carolina, with more than 900 care centers, including hospitals, nursing homes, doctors’ offices and surgical centers. The health system is placing its data, which include purchases a patient has made using a credit card or store loyalty card, into predictive models that give a risk score to patients.

Special Report: Putting Patient Privacy at Risk

Within the next two years, Dulin plans for that score to be regularly passed to doctors and nurses who can reach out to high-risk patients to suggest interventions before patients fall ill.

Buying Cigarettes

For a patient with asthma, the hospital would be able to score how likely they are to arrive at the emergency room by looking at whether they’ve refilled their asthma medication at the pharmacy, been buying cigarettes at the grocery store and live in an area with a high pollen count, Dulin said.

The system may also score the probability of someone having a heart attack by considering factors such as the type of foods they buy and if they have a gym membership, he said.

“What we are looking to find are people before they end up in trouble,” said Dulin, who is also a practicing physician. “The idea is to use big data and predictive models to think about population health and drill down to the individual levels to find someone running into trouble that we can reach out to and try to help out.”

While the hospital can share a patient’s risk assessment with their doctor, they aren’t allowed to disclose details of the data, such as specific transactions by an individual, under the hospital’s contract with its data provider. Dulin declined to name the data provider.

Greater Detail

If the early steps are successful, though, Dulin said he would like to renegotiate to get the data provider to share more specific details on patient spending with doctors.

“The data is already used to market to people to get them to do things that might not always be in the best interest of the consumer, we are looking to apply this for something good,” Dulin said.

While all information would be bound by doctor-patient confidentiality, he said he’s aware some people may be uncomfortable with data going to doctors and hospitals. For these people, the system is considering an opt-out mechanism that will keep their data private, Dulin said.

‘Feels Creepy’

“You have to have a relationship, it just can’t be a phone call from someone saying ‘do this’ or it just feels creepy,” he said. “The data itself doesn’t tell you the story of the person, you have to use it to find a way to connect with that person.”

Murry, the diabetes patient from Charlotte, said she already gets calls from her health insurer to try to discuss her daily habits. She usually ignores them, she said. She doesn’t see what her doctors can learn from her spending practices that they can’t find out from her quarterly visits.

“Most of these things you can find out just by looking at the patient and seeing if they are overweight or asking them if they exercise and discussing that with them,” Murry said. “I think it is a waste of time.”

While the patients may gain from the strategy, hospitals also have a growing financial stake in knowing more about the people they care for.

Under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, known as Obamacare, hospital pay is becoming increasingly linked to quality metrics rather than the traditional fee-for-service model where hospitals were paid based on their numbers of tests or procedures.

Hospital Fines

As a result, the U.S. has begun levying fines against hospitals that have too many patients readmitted within a month, and rewarding hospitals that do well on a benchmark of clinical outcomes and patient surveys.

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, which operates more than 20 hospitals in Pennsylvania and a health insurance plan, is using demographic and household information to try to improve patients’ health. It says it doesn’t have spending details or information from credit card transactions on individuals.

The UPMC Insurance Services Division, the health system’s insurance provider, has acquired demographic and household data, such as whether someone owns a car and how many people live in their home, on more than 2 million of its members to make predictions about which individuals are most likely to use the emergency room or an urgent care center, said Pamela Peele, the system’s chief analytics officer.

Emergency Rooms

Studies show that people with no children in the home who make less than $50,000 a year are more likely to use the emergency room, rather than a private doctor, Peele said.

UPMC wants to make sure those patients have access to a primary care physician or nurse practitioner they can contact before heading to the ER, Peele said. UPMC may also be interested in patients who don’t own a car, which could indicate they’ll have trouble getting routine, preventable care, she said.

Being able to predict which patients are likely to get sick or end up at the emergency room has become particularly valuable for hospitals that also insure their patients, a new phenomenon that’s growing in popularity. UPMC, which offers this option, would be able to save money by keeping patients out of the emergency room.

Obamacare prevents insurers from denying coverage because of pre-existing conditions or charging patients more based on their health status, meaning the data can’t be used to raise rates or drop policies.

New Model

“The traditional rating and underwriting has gone away with health-care reform,” said Robert Booz, an analyst at the technology research and consulting firm Gartner Inc. (IT) “What they are trying to do is proactive care management where we know you are a patient at risk for diabetes so even before the symptoms show up we are going to try to intervene.”

Hospitals and insurers need to be mindful about crossing the “creepiness line” on how much to pry into their patients’ lives with big data, he said. It could also interfere with the doctor-patient relationship.

The strategy “is very paternalistic toward individuals, inclined to see human beings as simply the sum of data points about them,” Irina Raicu, director of the Internet ethics program at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University, said in a telephone interview.

To contact the reporters on this story: Shannon Pettypiece in New York atspettypiece@bloomberg.net; Jordan Robertson in San Francisco atjrobertson40@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Reg Gale at rgale5@bloomberg.net Andrew Pollack

New Yorker: Good medicine, it seems, does not always feel good.

This is weird… it’s like doctors are calling themselves out as hucksters? Unable to manage conflicts of interest? Human?? In which case, they can stop carrying on as if they’re something superior.

http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/elements/2013/07/when-doctors-tell-patients-what-they-dont-want-to-hear.html

WHEN DOCTORS TELL PATIENTS WHAT THEY DON’T WANT TO HEAR

Unwilling to jeopardize the affection of his “favorite patient,” Dr. Reed instead summons the brazen and socially inept Dr. Mindy to do his dirty work. True to form, by the end of the scene, Mindy has offended the patient, which escalates into a shouting match until the patient tells Mindy that she’s the one who needs to lose some weight. Reed emerges, halo intact.

Though the scene marks a bad day for Mindy, I think it also heralds what could turn out to be a bad era for American medicine. Beyond the comedic exaggerations lies an age-old tension: Will our patients still like us if we tell them things they don’t want to hear? The challenge of communicating unpleasant, possibly profoundly upsetting information to patients is timeless. What has changed, however, is that physicians are now being judged, and compensated, based upon their ability to do it.

In October, 2012, Medicare débuted a new hospital-payment system, known as Value-Based Purchasing, which ties a portion of hospital reimbursement to scores on a host of quality measures; thirty per cent of the hospital’s score is based on patient satisfaction. New York City’s public hospitals recently decided to follow suit, taking the incentive scheme one step further: physicians’ salaries will be directly linked to patients’ outcomes, including their satisfaction. Other outpatient practices across the country have also started to base physician pay partly on satisfaction scores, a trend that is expected to grow.

But in a country that spends more per capita on health than any other, with results that remain mediocre in comparison, can we really expect that a nation of more satisfied patients will be a healthier nation over all?

Many insist that we can. One of the leading arguments for pay based on satisfaction, as described in a recent Wall Street Journal article titled “The Talking Cure for Health Care,” is that these incentives will improve patient-doctor communication, which will in turn lead to better health. As the article notes, “Doctors are rude. Doctors don’t listen. Doctors have no time. Doctors don’t explain things in terms patients understand.”

Few object to these generalizations. We’ve all had insensitive doctors who have left us confused and scared. I’m a physician, and I often find myself rushing, interrupting, and overwhelming patients with information. But if the path from good communication to better health is through a better understanding of risk factors and disease, then medicine poses a paradox: how much we understand tends to be inversely related to how well we think physicians have communicated.

Consider, for example, a recent study among patients with chronic kidney disease: the more knowledge patients had about their illness, the less satisfied they were with their doctors’ communication. Another study’s title asks, “How does feeling informed relate to being informed?” The answer: it doesn’t. The investigators surveyed over twenty-five hundred patients about decisions they had made in the previous two years, and found no over-all relationship between how informed patients felt and what they actually knew.

The disconnect between patients’ understanding of disease and their satisfaction with physicians is particularly pronounced for care at the end of life. In a recent study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, oncologists studied patients’ expectations of chemotherapy options. For these patients, with either end-stage colon or lung cancer, chemotherapy may provide some help, but it can also be toxic, and definitely doesn’t provide a cure. Doctors know this, but do patients?

In the study, sixty-nine per cent of patients with lung cancer, and eighty-one per cent of patients with colon cancer, did not understand that chemotherapy was not curative. This finding reminds that we have much to learn about how to communicate medical information to our patients. But it is the second finding that suggests why paying based on patient satisfaction isn’t the way to get us there: the more people understood about the grim nature of their prognosis, the less they liked their physicians.

Understanding that there is no cure for your disease is entirely different from understanding why you need to take a blood-pressure medication. Since I suspect that a bit of denial is precisely what allows the dying to live—see the response of a young, pregnant woman to the news that she has incurable lung cancer in Atul Gawande’s “Letting Go” for a beautiful example—I tend to be more concerned with how to keep people from getting sick in the first place.

And this gets us back to the Mindy problem. Sure, there are nice ways of saying, “You need to lose weight, stop smoking, and take this medication that certainly won’t make you feel better but might very well leave you tired and depressed.” But sometimes there aren’t, and it can be tough to separate how we feel about the message from how we feel about the messenger.

I used to be an avid runner, but have had a slew of running injuries—the most enduring of which is a chronic hamstring problem that has made sitting uncomfortable, and running impossible. But for a long time, my approach to any given injury was simple: run through it.

In my quest for quick fixes, I have seen more orthopedists than I can count. But there was one doctor, Dr. D., who tried to teach me the error of my ways. He told me that the problem was not with my body but with my behavior. He said I didn’t need MRIs or steroid injections but rather to stop running and give myself time to heal. And I, in turn, found much that was wrong with him: he started late, didn’t return phone calls, had bad breath, typed with one finger, and, above all, didn’t seem to listen to me. I decided he was the worst doctor in the world and went searching for a new one.

Many months and doctors later, last year, I found “my person.” Most important, she told me I would run again. That she was so nice, so pretty, and so put together (and she injected my aching gluteal region with steroid every time I asked) only reinforced my sense that I was in the most expert of hands. I loved her as much as I wanted to be her.

If you had mailed me a satisfaction survey, you can imagine which doctor would have gotten a bonus. But in the end, it’s Dr. D who was right. I still can’t run, but had I heeded his advice, I’d likely be back to doing marathons.

The problem with the patient-satisfaction surveys is that they assume we can evaluate specific characteristics of doctors, or hospitals, as distinct from their general likability. But that’s not easy. The halo effect is a well known cognitive bias that describes our tendency to quickly judge people and then assume the person possesses other good or bad qualities consistent with that general impression. The effect is perhaps best described in the many positive attributes we ascribe to someone we find attractive. As the Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman noted, for example, “If we think a baseball pitcher is handsome and athletic … we are likely to rate him better at throwing the ball, too.”

This tendency has been well demonstrated in our judgments of the competence of political candidates, or our willingness to assume innocence for someone accused of a crime. (See Paul Bloom’s post on the unwarranted empathic response to the attractive face of the Boston Marathon bomber Dzokhar Tzarnaev.) Though there are several factors informing the general likability of physicians beyond how we feel about what they tell us, there is no reason to assume we would be somehow immune to this cognitive bias when it comes time to rate them.

Although we tend to be totally unaware of the effects of these haloes on our own judgments, hospitals and outpatient practices are not. That’s why they are investing millions of dollars in renovated rooms, new foyers, gourmet chefs, and valet parking. These are nice perks, and undoubtedly lead to higher scores across all domains of the satisfaction survey.

But do higher scores on a satisfaction survey translate into better health? So far, the answer seems to be no. A recent study examined patient satisfaction among more than fifty thousand patients over a seven-year period, and two findings were notable. The first was that the most satisfied patients incurred the highest costs. The second was that the most satisfied patients had the highest rates of mortality. While with studies like this one it is always critical to remember that correlation does not equal causation, the data should give us pause. Good medicine, it seems, does not always feel good.

Lisa Rosenbaum is a cardiologist, a Fellow at the Philadelphia V.A. Medical Center, and a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholar at the University of Pennsylvania.

Photograph: Fox

The many reasons why the US is losing in health

- very interesting piece

- covers off Cth Fund and IOM comparative work

- also discusses social determinants, and specifically the idea that less equal societies are comparatively less healthy across the board (including the wealthy)

- The critical importance of poverty prevalence in a country’s health (AU is 12.5% c.f. average of 9% cf. US of 15%)

Woolf explained this disparity by citing the work of the British social epidemiologist Richard Wilkinson, who has proposed that income inequality generates adverse health effects even among the affluent. Wide gaps in income, Wilkinson argues, diminish our trust in others and our sense of community, producing, among other things, a tendency to underinvest in social infrastructure. Furthermore, Woolf told me, even wealthy Americans are not isolated from a lifestyle filled with oversized food portions, physical inactivity, and stress. Consider the example of paid parental leave, for which the United States ranks dead last among O.E.C.D. countries. It’s not hard to see how such policies might have implications for infant and child health.

- Political systems have important effects on policy: fewer “choke points for special interests to block or reshape legislation,” such as filibusters or Presidential vetoes allows change to be enacted without extensive political negotiation.

Other countries have used their governments as instruments to improve health—including, but not limited to, the development of universal health insurance. Health-policy analysts have therefore considered the effect that different political systems have on public health. Most O.E.C.D. countries, for example, have parliamentary systems, where the party that wins the majority of seats in the legislature forms the government. Because of this overlap of the legislative and executive branches, parliamentary systems have fewer checks and balances—fewer of what Victor Fuchs, a health economist at Stanford, calls “choke points for special interests to block or reshape legislation,” such as filibusters or Presidential vetoes. In a parliamentary system, change can be enacted without extensive political negotiation—whereas the American system was designed, at least in part, to avoid the concentration of power that can produce such swift changes.

- universal health coverage is not just altruistic, but also self-interested

- healthcare is only responsible for between 10 and 25% of improvements in life expectancy – SDH responsible for the rest, mainly elements that impact on early childhood

Most experts estimate that modern medical care delivered to individual patients—such as physician and hospital treatments covered by health insurance—has only been responsible for between ten and twenty-five percent of the improvements in life expectancy over the last century. The rest has come from changes in the social determinants of health, particularly in early childhood.

http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/elements/2014/06/why-america-is-losing-the-health-race.html

WHY AMERICA IS LOSING THE HEALTH RACE

The second report, commissioned by the National Institutes of Health, and conducted by the National Research Council (NRC) and the Institute of Medicine (IOM), convened a panel of experts to examine health indicators in seventeen high-income countries. It found the United States in a similarly poor position: American men had the lowest life expectancy, and American women the second-lowest. In some ways, these reports were not news. As early as the nineteen-seventies, a group of leading health analysts had noted the discrepancy between American health spending and outcomes in a book called “Doing Better and Feeling Worse: Health in the United States.” From this perspective, the U.S. has been doing something wrong for a long time. But, as the first of these two reports shows, the gap is widening; despite spending more than any other country, America ranks very poorly in international comparisons of health. The second report may provide an answer—supporting the intuition long held by researchers that social circumstances, especially income, have a significant effect on health outcomes.

Americans’ health disadvantage actually begins at birth: the U.S. has the highest rates of infant mortality among high-income countries, and ranks poorly on other indicators such as low birth weight. In fact, children born in the United States have a lower chance of surviving to the age of five than children born in any other wealthy nation—a fact that will almost certainly come as a shock to most Americans. But what causes such poor health outcomes among American children, and how can those outcomes be improved? Public-health experts focus on the “social determinants of health”—factors that shape people’s health beyond their lifestyle choices and medical treatments. These include education, income, job security, working conditions, early-childhood development, food insecurity, housing, and the social safety net.

Steven Schroeder, the former president of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation—the largest philanthropic organization in the United States devoted to health issues—had a definitive answer to my question about why Americans might be less healthy than their developed-country counterparts. “Poverty,” he said. “The United States has proportionately more poor people, and the gap between rich and poor is widening.” Seventeen per cent of Americans live in poverty; the median figure for other O.E.C.D. countries is only nine percent. For three decades, America has had the highest rate of child poverty of any wealthy nation.

Steven Woolf, of Virginia Commonwealth University, who chaired the panel that produced the NRC-IOM report, also pointed to poverty when I asked him to explain the causes of America’s health disadvantage. “Could there possibly be a common thread that leads Americans to have higher rates of infant mortality, more deaths from car crashes and gun violence, more heart disease, more AIDS, and more premature deaths from drugs and alcohol? Is there some common denominator?” he asked. “One possibility is the way Americans, as a society, manage their affairs. Many Americans embrace rugged individualism and reject restrictions on behaviors that pose risks to health. There is less of a sense of solidarity, especially with vulnerable populations.” As a percentage of G.D.P., Woolf observed, the U.S. invests less than other wealthy countries in social programs like parental leave and early-childhood education, and there is strong resistance to paying taxes to finance such programs. The U.S. ranks first among O.E.C.D. countries in health-care expenditures, but as Elizabeth Bradley, a researcher at Yale, has documented, it ranks twenty-fifth in spending on social services.

The NRC-IOM report emphasized the effect of social forces on children and how those forces carry over to affect the health of adults, noting that American children are “more likely than children in peer countries to grow up in poverty” and that “poor social conditions during childhood precipitate a chain of adverse life events.” For example, of the seventeen wealthy democracies included in the report, the U.S. has the highest rates of adolescent pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases, and the second-highest prevalence of H.I.V. This platform of adverse health influences in childhood sets up the health disadvantage that remains pervasive for all age groups under seventy-five in the United States.

It seems likely that many Americans would respond to these figures—and to the role poverty plays in poor health outcomes—by assuming that the data for all Americans is being skewed downward by the health of the poorest. That is, they understand that poor Americans have worse health, and presume that, because the United States has more poor people than other wealthy countries, the average health looks worse. But one of the most interesting findings in the NRC-IOM report is that even white, college-educated, high-income Americans with healthy behaviors have worse health than their counterparts in other wealthy countries.

Woolf explained this disparity by citing the work of the British social epidemiologist Richard Wilkinson, who has proposed that income inequality generates adverse health effects even among the affluent. Wide gaps in income, Wilkinson argues, diminish our trust in others and our sense of community, producing, among other things, a tendency to underinvest in social infrastructure. Furthermore, Woolf told me, even wealthy Americans are not isolated from a lifestyle filled with oversized food portions, physical inactivity, and stress. Consider the example of paid parental leave, for which the United States ranks dead last among O.E.C.D. countries. It’s not hard to see how such policies might have implications for infant and child health.

Other countries have used their governments as instruments to improve health—including, but not limited to, the development of universal health insurance. Health-policy analysts have therefore considered the effect that different political systems have on public health. Most O.E.C.D. countries, for example, have parliamentary systems, where the party that wins the majority of seats in the legislature forms the government. Because of this overlap of the legislative and executive branches, parliamentary systems have fewer checks and balances—fewer of what Victor Fuchs, a health economist at Stanford, calls “choke points for special interests to block or reshape legislation,” such as filibusters or Presidential vetoes. In a parliamentary system, change can be enacted without extensive political negotiation—whereas the American system was designed, at least in part, to avoid the concentration of power that can produce such swift changes.

Whatever the political obstacles, a major explanation for America’s persistent health disadvantage is simply a lack of public awareness. “Little is likely to happen until the American public is informed about this issue,” the authors of the NRC-IOM report noted. “Why don’t Americans know that children born here are less likely to reach the age of five than children born in other high income countries?” Woolf asked. I suggested that perhaps people believe that the problem is restricted to other people’s children. He said, “We are talking about their children and their health too.”

The superior health outcomes achieved by other wealthy countries demonstrate that Americans are—to use the language of negotiators—“leaving years of life on the table.” The causes of this problem are many: poverty, widening income disparity, underinvestment in social infrastructure, lack of health insurance coverage and access to health care. Expanding insurance coverage under the Affordable Care Act will help, but pouring more money into health care is not the only answer. Most experts estimate that modern medical care delivered to individual patients—such as physician and hospital treatments covered by health insurance—has only been responsible for between ten and twenty-five percent of the improvements in life expectancy over the last century. The rest has come from changes in the social determinants of health, particularly in early childhood.

Self-interest may be a natural human trait, but when it comes to public health other countries are showing the U.S. that what appears at first to be an altruistic concern for the health and care of the most vulnerable—especially children—may well result in improved health for all members of a society, including the affluent. Until Americans find their way to understanding this dynamic, and figure out how to mobilize public opinion in its favor, they will all continue to lose out on better health and longer lives.

Allan S. Detsky (M.D., Ph.D.) is a general internist and a professor of Health Policy Management and Evaluation and of Medicine at the University of Toronto, where he was formerly physician-in-chief at Mount Sinai Hospital. He is a contributing writer for The Journal of the American Medical Association.

Photograph by Ashley Gilbertson /VII.

Blumenthal: On the need for the leaders to be IT savy

http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/blog/2014/jun/of-leaders-and-geeks

Of Leaders and Geeks

Tuesday, June 24, 2014

- An IT failure (healthcare.gov) nearly destroys a president’s legacy, while a seeming IT triumph (the National Security Agency’s electronic snooping skills) throws his foreign policy into turmoil.

- According to Michael Lewis’ fascinating and scary book, Flash Boys, Wall Street geeks make billions through high-frequency trading, running circles around clueless masters of the universe in charge of America’s biggest banks and hedge funds.

- For the second year in a row, the American Medical Association elects a health IT expert as its president.

This could be nothing. But then again, could it be something really big? Could we be witnessing a fundamental change in the requirements for leadership in health and every other sector of society?

We all live with stereotypes and here is one of the most powerful: We have leaders and we have geeks. Leaders change history. They sit atop governments and corporations. They craft strategy, cut deals, rally the troops, and guide humanity into the future. They don’t need to understand technology, because they have geeks.

Geeks sit in cubicles off-site somewhere. They spend their days coding, wiring, and rushing to help impatient leaders whose systems are down. Geeks show up when they’re needed, and go away when they’re not. The technology they manage is like plumbing or electricity. If you don’t like your plumber or electrician, there’s always another in the wings.

Leaders don’t have to manage geeks. They have people who have people who manage geeks.

Like all stereotypes, this one is exaggerated and not wholly accurate, but it makes a point. In health and other areas, leaders sometimes take a kind of perverse pride in their ignorance of information technology and how it works. It’s as though familiarity with IT would damage the aura that qualifies them for the huge responsibilities they seek and enjoy. Of course, they may have content expertise acquired during their rise through the ranks. In health care, it may be training and experience as a health professional and/or academician; in business, it may be marketing or finance; in government, it may be elected office or policy expertise. But almost never is an understanding of information technology considered a vital ingredient in preparing leaders to assume their great responsibilities.

There are exceptions. The leaders of some of the world’s most successful new companies—Microsoft, Google, Apple, Facebook—are or have been technologists. But they run technology companies. It makes sense that for this industrial sector, real geeks should sit in the CEO’s office. But for most of the rest of our public and private enterprises, the gap between technology experts and leaders persists.

This may be changing. Recent history suggests that at least for health care leaders—whether in government or the private sector—a deep appreciation for, and even understanding of, information technology may be a vital asset. How could it be otherwise? In health care, as elsewhere, information is power: not only the power to heal, but also the power to improve quality, efficiency, reliability, safety, and value. And information technology, acting as a health care organization’s circulatory system, collects, manages, and circulates that information.

Today’s and tomorrow’s successful leaders do not need to be technologists, but they do have to own technology policy and problems in a way few do right now. And they have to incorporate into their inner circles of advisers individuals capable of bridging the historical divide between technology experts and leaders. The alternative could be a future full of healthcare.gov launches, or worse, a continuing failure to take full advantage of the power of information to optimize health system performance.