the health sector is riddled with a fear of change trumped only by its fear of accountability

me just then en route to nate gross talk at powerhouse

Category Archives: storytelling

“Eat right. Get physical activity. Don’t smoke. Alcohol in moderation. Spend time with friends.”

http://www.vox.com/health-care/2014/4/22/5640636/dont-read-more-health-books-read-these-14-words

Don’t read more health books. Read these 14 words.

Thomas Frieden has a scary job. As director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, he gets the call when infections begin defeating all known antibiotics, or Ebola resurfaces, or overdoses from prescription opiates begin skyrocketing.

Meanwhile, I’m the kind of person who won’t even go see movies about disease outbreaks. So when I sat down with Frieden recently, I asked him the question hypochondriacs need to know: What has all this data taught him to fear? What does he tell his family to do differently?

His answer was borderline dull:

Very little is different really. It’s basic. Wash your hands regularly. Get regular physical activity. Eat foods you love that are healthy. That’s one of the things that’s so challenging. Take physical activity as an example. You don’t have to have much, 30 minutes a day. Doing that, which can be three 10-minute walks, is going to make a huge difference in your life. You’ll feel better even if you don’t lose an ounce. You will be much less likely to have high blood pressure, high cholesterol, cancer, arthritis, depression. You’ll sleep better. And it doesn’t cost a cent.

There’s a lot a of things that can be done that are not very difficult and can make a really big difference. Of course, get your shots, get vaccination, get a flu shot every year and see the doctor regularly and if you have a problem make sure to get follow up.

The broader point — which came up again and again in our interview — is that the main threats to health aren’t spectacular. People die from heart disease, car accidents, and tobacco a lot more often than they’re killed by Ebola, terrorism, and heroin.

The CDC Director’s reply reminded me of Michael Pollan’s famous, commonsense triplet about diet: “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.” I asked whether Frieden had similarly concise advice. He did.

“Eat right. Get physical activity. Don’t smoke. Alcohol in moderation. Spend time with friends.”

Unlike a lot of health treatments, weird diets, and fancy exercise regimes you’ll read about, this advice is backed up by reams of rock-solid evidence — and following it costs next to nothing.

So there it is: in less than 15 words, the US official who probably knows better than anyone else what might kill you explains how to protect yourself.

Here’s my full interview with Frieden:

- 373Tweet

- Share

I am an entrepreneur…

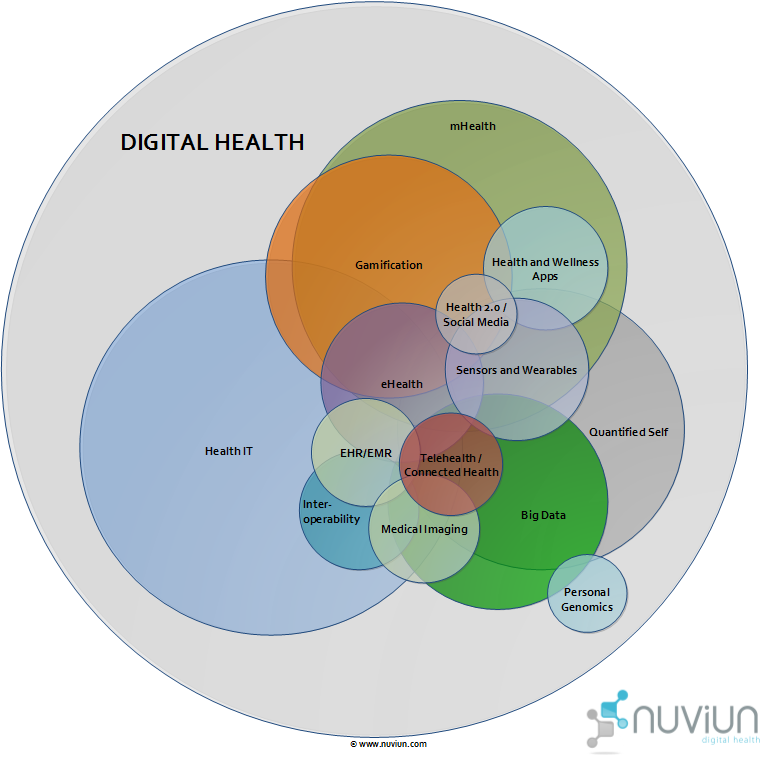

The Story of Digital Health

http://www.nuviun.com/nuviun-digital-health

good infographics…

http://storyofdigitalhealth.com/infographic/

Infographic

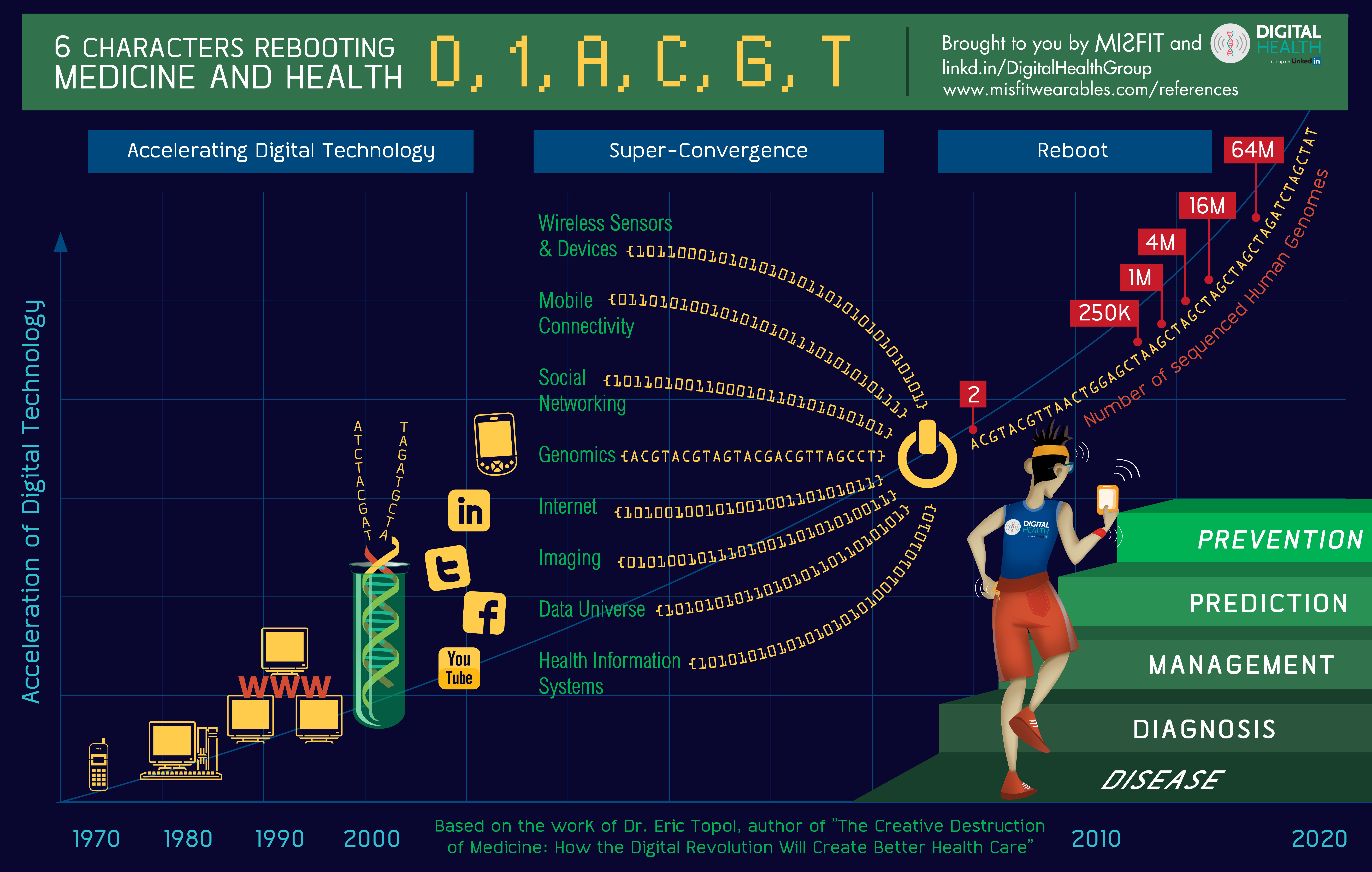

I created this conceptual infographic illustrating the increasing health benefits achievable with digital health with the great team at Misfit Wearables. You can download a high-resolution version by clicking on the image.

References:

Number of people sequenced

“250,000 human genomes will be fully sequenced by the end of 2012, 1 million by 2013, and 5 million by 2014″ -Topol, Eric (2011-12-02). The Creative Destruction of Medicine: How the Digital Revolution Will Create Better Health Care (p. 102). Perseus Books Group. Kindle Edition.

Also, compliments of Story of Digital Health strategic partner nuviun, there’s this interactive diagram of the digital health landscape…

When I Die…

an idea of earth shattering significance

ok.

been looking for alignment between a significant industry sector and human health. it’s a surprisingly difficult alignment to find… go figure?

but I had lunch with joran laird from nab health today, and something amazing dawned on me, on the back of the AIA Vitality launch.

Life (not health) insurance is the vehicle. The longer you pay premiums, the more money they make.

AMAZING… AN ALIGNMENT!!!

This puts the pressure on prevention advocates to put their money where their mouth is.

If they can extend healthy life by a second, how many billions of dollars does that make for life insurers?

imagine, a health intervention that doesn’t actually involve the blundering health system!!?? PERFECT!!!

And Australia’s the perfect test bed given the opt out status of life insurance and superannuation.

Joran wants to introduce me to the MLC guys.

What could possibly go wrong??????

Three simple rules in life

c/o Josh Wills (Cloudera, ex Google) from this presentation.

Three simple rules in life:

- If you do not go after what you want, you’ll never have it

- If you do not ask, the answer will always be no

- If you do not step forward, you will always be in the same place

Disinformation Visualization

Good, clean, wholesome analytics home truths…

Disinformation Visualization: How to lie with datavis

By Mushon Zer-Aviv, January 31, 2014

Seeing is believing.

When working with raw data we’re often encouraged to present it differently, to give it a form, to map it or visualize it. But all maps lie. In fact, maps have to lie, otherwise they wouldn’t be useful. Some are transparent and obvious lies, such as a tree icon on a map often represents more than one tree. Others are white lies – rounding numbers and prioritising details to create a more legible representation. And then there’s the third type of lie, those lies that convey a bias, be it deliberately or subconsciously. A bias that misrepresents the data and skews it towards a certain reading.

It all sounds very sinister, and indeed sometimes it is. It’s hard to see through a lie unless you stare it right in the face, and what better way to do that than to get our minds dirty and look at some examples of creative and mischievous visual manipulation.

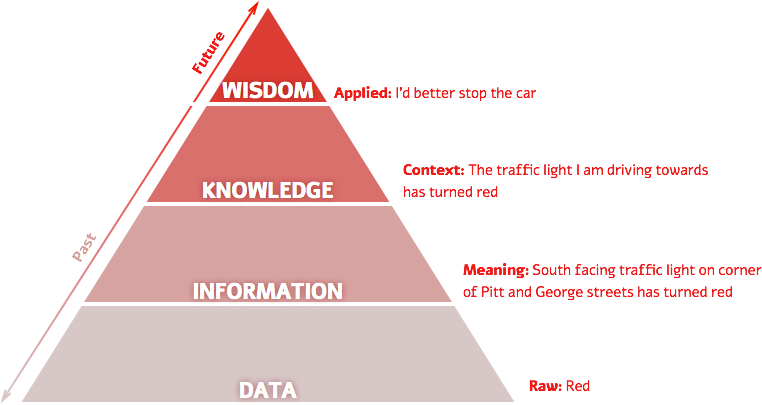

Over the past year I’ve had a few opportunities to run Disinformation Visualization workshops, encouraging activists, designers, statisticians, analysts, researchers, technologists and artists to visualize lies. During these sessions I have used the DIKW pyramid (Data > Information > Knowledge > Wisdom), a framework for thinking about how data gains context and meaning and becomes information. This information needs to be consumed and understood to become knowledge. And finally when knowledge influences our insights and our decision making about the future it becomes wisdom. Data visualization is one of the ways to push data up the pyramid towards wisdom in order to affect our actions and decisions. It would be wise then to look at visualizations suspiciously.

Centuries before big data, computer graphics and social media collided and gave us the datavis explosion, visualization was mostly a scientific tool for inquiry and documentation. This history gave the artform its authority as an integral part of the scientific process. Being a product of human brains and hands, a certain degree of bias was always there, no matter how scientific the process was. The effect of these early off-white lies are still felt today, as even our most celebrated interactive maps still echo the biases of the Mercator map projection, grounding Europe and North America on the top of the world, over emphasizing their size and perceived importance over the Global South. Our contemporary practices of programmatically data driven visualization hide both the human brains and eyes that produce them behind data sets, algorithms and computer graphics, but the same biases are still there, only they’re harder to decipher.

“All that is necessary for evil to triumph is for good men to do nothing”

“All that is necessary for evil to triumph is for good men to do nothing” – paraphrased from Tolstoy

Probably not Edmund Burke… http://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Edmund_Burke

On wearables

The point isn’t the gadget: it’s the combination of the intimacy of a device that is always with us and that only we use, with the power of cloud-based processing and storage. The wearable device itself is actually only the small, physical manifestation of a much larger service: Google Glass gives its wearers a head-up display, voice control and a forward-facing camera, but it’s only through a connection to the internet that it can live up to its potential

“He put this engine into our ears,” wrote the Lilliputians, in Gulliver’s Travels, Jonathan Swift’s 1726 classic, “which made an incessant noise, like that of a water-mill: and we conjecture it is either some unknown animal, or the god that he worships; but we are more inclined to the latter opinion, because he assured us, (if we understood him right, for he expressed himself very imperfectly) that he seldom did any thing without consulting it. He called it his oracle and said it pointed out the time for every action of his life.”

Just as Gulliver’s Travels was a satire, and its description of his watch essentially a tease on time-based affairs, so too we are starting to find that the accoutrements of our modern communications are ripe for mickey-taking. The Bluetooth headset has gone from a status symbol to the mark of a tosser. There’s a Britishness to this — a who do you think you are to need such a device? thing. There’s also a feeling of enslavement that might be hard to shake. Just as our culture turns towards reducing the digital distraction in our lives, will we really want to be cuffed to our inbox? It’s said that in a ham-and-egg sandwich, the chicken is involved but the pig is committed: just how committed to our communications do we want to — or want to appear to — actually be?

“It’s not information overload. It’s filter failure.” Clay Shirky

http://www.wired.co.uk/magazine/archive/2014/01/features/the-third-wave-of-computing

Wearables: the third wave of computing

TECHNOLOGY

23 JANUARY 14 by BEN HAMMERSLEY

This article was taken from the January 2014 issue of Wired magazine. Be the first to read Wired’s articles in print before they’re posted online, and get your hands on loads of additional content by subscribing online.

Wearables are truly upon us. It takes about a decade to shift: from the basements of the 70s, to the desks of the 80s, the laps of the 90s, the front rooms of the noughties and pockets of the twenty teens, the location of hot computing — the place where the most interesting developments are happening — always moves and shrinks with every generation. And although this decade is all about the smartphone, today we’re starting to see the path to the next stop in this constant progression: if not in, then definitely on the body.

As we’ll discuss, this leap, from the situated and leave-behindable to the always-on, always-present, always–connected, is not without its drawbacks. But it also promises a near-future world of self-knowledge, sensors and superpowers. Even today we can monitor our activities and compare ‘n’ share with our friends via devices such as the Nike+ FuelBand, the Fitbit or the Jawbone UP; and we can bring information, alerts and alarms to our wrist with devices like the Pebble watch. Coming devices will give you head-up displays, vibrating interfaces, speech recognition and a constant –understanding of where you and it are in time and space. By smearing the interface between –yourself and the internet across your nervous system, wearables are the first step in augmentation of the human. They give us superpowers in the same way cybernetic implants do to the heroes of science fiction.

The point isn’t the gadget: it’s the combination of the intimacy of a device that is always with us and that only we use, with the power of cloud-based processing and storage. The wearable device itself is actually only the small, physical manifestation of a much larger service: Google Glass gives its wearers a head-up display, voice control and a forward-facing camera, but it’s only through a connection to the internet that it can live up to its potential.

And what potential — never forget a name again, thanks to its camera, facial-recognition tech and a link to your social networks. Never be lost, through the map hovering in the corner of your eye. Develop an instant expertise in the art you’re looking at with a reverse image-search and a Wikipedia lookup. Have perfect memories of everything you do, say, see or hear through a constant archive of point-of-view shot from your forehead. Be a more scintillating conversationalist by recording, transcribing and automatically Googling everything you hear. Link your devices and adjust your day’s agenda to match your pulse-rate-monitored stress levels. Receive an ambient alert to your wrist whenever you’re close to something that’s on your phone-stored shopping list, and whisper to your glasses to show you where it is on the shelf. Feel a tingle in your pocket when you walk past someone whose OKCupid profile matches your own, and whose biomonitoring devices -indicate is in a receptive mood. Automatically plot a route to work that takes you past breakfast places whose menus match your immediate biochemical needs, and have this hover in front of you as you cycle, with warnings for when you’re pedalling too hard for your heart, and notifications of upcoming meetings being cancelled, as you sub-vocalise acknowledgements in English, having them translated in real-time into the Japanese of your colleague’s wrist-bound diary.

Many of these scenarios are dependent on different devices, from different manufacturers, successfully talking to each other: for wearables to sing the body electric, they must first form choirs. Rival firms will have to adopt compatible standards and allow for truly open development before the more advanced ideas are possible. But these are engineering and business decisions. More important for wearables, with their curious mix of the intimate and the public, is the social reaction to their use.

The surest sign of a technological niche about to be filled is an outbreak of Apple rumours. No other firm produces such a flurry of speculation, guesswork and extrapolation of minor signals as Apple. The iWatch (name by popular consensus) has never been mentioned by anyone from Apple, nor has anyone from its supply chain spoken of it or leaked any details, but nevertheless there are signs that such a thing might be on its way.

Apple has a handful of patents that look useful, plus there are a few details in the new iPhone and iOS that would make a lot of sense if an iWatch existed. The iPhone 5s has a chip dedicated to monitoring its owner’s movements, making it in essence a pocket-carried FuelBand, which shows that Apple is at least paying attention to the quantified-self idea. And iOS7 has a feature, iBeacon, which allows for communication with low-powered devices using the newest Bluetooth standard. That would be very useful over the range between your pocket and your wrist. Siri, the voice interface on iOS, would be splendid on a wearable, and the iOS notifications screen looks eminently transferable. But all of this is, of course, entirely conjecture. The beguiling/tiring axis of Apple product fantasies is subject to the traditional Apple announcement-and-launch schedule, and the likely slot for the Next Big Thing is the mid-January keynote, just in time to make everyone look mournfully at their month-old but now painfully past-it Christmas presents.

Like many internet technologies, wearables are very much a product of the environment in which they are funded and designed, primarily that of Silicon Valley — both the physical place and its thought-construct offshoots around the world. Invariably, the use-case scenarios for wearables both address problems that are two degrees away from behaviours not already invested in, and furthermore take a technofundamentalist position on existing social norms.

To think about this, consider that there are two classes of wearables today: the introspective, which monitors what you do and where you go, and informs you of changes to the state of your body and expanded self in cyberspace; and the extrospective, which looks outwards, to monitor and record the world around you. A Nike+ FuelBand is introspective. A Narrative Clip cam, which takes pictures constantly as you wear it, is extrospective. The introspective is of no concern to others. Who cares if you’re counting your steps? But the extrospective is a different beast. Society has yet to evolve the correct etiquette for having a meeting with someone who is constantly recording and archiving their conversations, or for going to a party with someone whose necklace is uploading pictures of you to the cloud every 30 seconds. It is as hard to imagine future generations’ views on these things as it is today to understand the Victorians’ erotic desire for table legs. But today’s society might find it challenging, if not already illegal, under different countries’ privacy laws. You may be able to remember the faces of all the people you meet, but use a device to capture them automatically and put them into a database, and a line is being crossed — even if that data is inaccessible to others. Whether that line demarcates violating others’ privacy — or breaking your own sense of non-augmented humanity — is something we will have to hash out.

Some wearable technology has already developed a level of understood etiquette. A glance at your watch in the middle of a meeting is rude. But it’s also an action that is understood by the person you are meeting: you wanted to know the time. Wearables, especially those with displays that cannot be seen by others, go much further than this. You may be aware that the other person just interacted with their device, but you have no idea what that interaction was. As interfaces become more ambient, or more fluid, the social meaning of interacting with them mid-conversation becomes more confused and potent. Today’s one-on-one conversations might be tomorrow’s one-on-one-plus-her-fact-checking-AI conversations. Just what did that mid-conversation microdistraction mean? That your lies have been found out, or that their football team just scored? It will be unnerving.

Valley-based technologists, however, may take the more fundamentalist view that it is not their technologies’ place to deal with human insecurities, but rather society’s job. The ideology of what it is possible to do with the technology is paramount, and human squeamishness has no role to play: a sort of device-led fait accompli. This is already happening, for example, in the concerns expressed around the supposed inability of the digital world to forget youthful indiscretions, prompting the then CEO of Google, Eric Schmidt, to suggest that in the future, people might change their name at a certain age to reset their online identity. Wearables could accelerate this process.

The social and the technical are inevitably interlinked. Although wearables have themselves been enabled by advances in chip design and component miniaturisation, it is perhaps that relentless technological progress that precedes their downfall. There is an old joke in software design that all programs expand until they can receive email. Likewise, we might suspect that all tiny devices will upgrade until they are general–purpose computers. This has already happened with phones — the iPhone 5S is purportedly as powerful as a MacBook Pro from 2008 — but phones can be put away, or obviously turned off. A wristband that today might be expected to just count your steps could, in theory, be programmed to record all that happens around it, upload that data to the cloud and do something mysterious with it. We are never sure about how new technologies will be received, and history is full of examples of our willingness to accept new deskbound technologies. Wearables, –however, push tech into the fields of fashion, of social signifier and public display. At your laptop, in private, you’re hard to judge. Use these technologies in public, and they enter a different realm.

“He put this engine into our ears,” wrote the Lilliputians, in Gulliver’s Travels, Jonathan Swift’s 1726 classic, “which made an incessant noise, like that of a water-mill: and we conjecture it is either some unknown animal, or the god that he worships; but we are more inclined to the latter opinion, because he assured us, (if we understood him right, for he expressed himself very imperfectly) that he seldom did any thing without consulting it. He called it his oracle and said it pointed out the time for every action of his life.”

Just as Gulliver’s Travels was a satire, and its description of his watch essentially a tease on time-based affairs, so too we are starting to find that the accoutrements of our modern communications are ripe for mickey-taking. The Bluetooth headset has gone from a status symbol to the mark of a tosser. There’s a Britishness to this — a who do you think you are to need such a device? thing. There’s also a feeling of enslavement that might be hard to shake. Just as our culture turns towards reducing the digital distraction in our lives, will we really want to be cuffed to our inbox? It’s said that in a ham-and-egg sandwich, the chicken is involved but the pig is committed: just how committed to our communications do we want to — or want to appear to — actually be?

As timepieces, wristwatches have been generally replaced by the clock on your phone. But that notwithstanding, a cheap digital watch keeps the time as well as the most expensive chronometers. Spending more than £5 on a watch is not a decision of practical use: the men’s watch market, for example, is now almost entirely one of fashion, of signifiers of wealth, of male-accepted jewellery — either that, or wine bars are popular with deep-sea divers.

But that market is based entirely on notions of craftsmanship, tradition and symbols of supposed manliness that are notably absent with the sort of wearable technologies we’re talking about here. Equating rapidly innovating devices with luxury misses the point of either: you can stick jewels to something, or you can make it super rugged, but neither of those will take away from the fact that they are functional devices, soon to be declared obsolete and upgraded. They’re built to do a job; on the nature of that job will you be judged — and that job might be nerdy.

The slow roll-out of Google Glass is a case in point. It is undoubtedly amazing technology and there are plenty of use-cases for wearing it while doing something else. But even before anyone had seen it in the wild, there was a word for people wearing it casually around the place: “glassholes”. Already dubbed “a Segway for the face”, Google Glass may turn out to be the most useful thing ever, but wear it all the time and you’ll be put into the same social slot as people with shoulder-holsters for their BlackBerry.

Ultimately, though, that’s a question of marketing and the transformation of social norms. So too is our commitment to our data. The recent fashions of unplugging, digital detoxing, email fasts and screen-break sabbaths have highlighted the desire of many to be free from the constant flow of information. As an activity that happens in front of a large, special-purpose machine on our desks, this feels like work, even when it’s play.

The limitations of the devices might be their, and our, saviour in this regard. As NYU professor and writer Clay Shirky says, “It’s not information overload. It’s filter failure.” Perhaps the limited size of the display, the cruder signalling from a wearable device, will encourage developers to refine those filters. If all you can display is a few lines of text, or if it’s one vibration for left and two for right, then the filtering will need to be done by the system, and not by the user. The stupid device being the pointy end of complex software places the responsibility for technological sophistication back into the laps of the programmers and designers.

Wearable technologies promise a great deal. For the individual, their usefulness, their very intimacy, offers a levelling-up of personal ability and self–understanding. One app that already exists for the iPhone, Word Lens, offers real-time translation of printed text, such as street signs, in the video camera, laid over the original text. That or something like it will be a Google Glass app sooner or later.

The barrier between the internet and the rest of the world is weakened by wearables, and their technology is no longer a personal matter. Using them might prove to be — in circumstances of extrospection, or of massive–augmentation of personal ability — considered socially unacceptable, unfair or just uncool. How that social progress plays out will be just as interesting as the technology itself. Personal computing is no longer personal. We will wear it like we wear our heart: on our sleeve.