Artificial intelligence meets the C-suite

http://www.mckinsey.com/Insights/Strategy/Artificial_intelligence_meets_the_C-suite

Jeremy Howard: Today, machine-learning algorithms are actually as good as or better than humans at many things that we think of as being uniquely human capabilities. People whose job is to take boxes of legal documents and figure out which ones are discoverable— that job is rapidly disappearing because computers are much faster and better than people at it.

In 2012, a team of four expert pathologists looked through thousands of breast-cancer screening images, and identified the areas of what’s called mitosis, the areas which were the most active parts of a tumor. It takes four pathologists to do that because any two only agree with each other 50 percent of the time. It’s that hard to look at these images; there’s so much complexity. So they then took this kind of consensus of experts and fed those breast-cancer images with those tags to a machine-learning algorithm. The algorithm came back with something that agreed with the pathologists 60 percent of the time, so it is more accurate at identifying the very thing that these pathologists were trained for years to do. And this machine-learning algorithm was built by people with no background in life sciences at all. These are total domain newbies

Artificial intelligence meets the C-suite

Technology is getting smarter, faster. Are you? Experts including the authors of The Second Machine Age, Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee, examine the impact that “thinking” machines may have on top-management roles.

September 2014

The matter is more than academic. Many of the jobs that had once seemed the sole province of humans—including those of pathologists, petroleum geologists, and law clerks—are now being performed by computers.

And so it must be asked: can software substitute for the responsibilities of senior managers in their roles at the top of today’s biggest corporations? In some activities, particularly when it comes to finding answers to problems, software already surpasses even the best managers. Knowing whether to assert your own expertise or to step out of the way is fast becoming a critical executive skill.

Video

Managing in the era of brilliant machines: An interview

In this interview with McKinsey’s Rik Kirkland, Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee explain the organizational challenge posed by the Second Machine Age.

Yet senior managers are far from obsolete. As machine learning progresses at a rapid pace, top executives will be called on to create the innovative new organizational forms needed to crowdsource the far-flung human talent that’s coming online around the globe. Those executives will have to emphasize their creative abilities, their leadership skills, and their strategic thinking.

To sort out the exponential advance of deep-learning algorithms and what it means for managerial science, McKinsey’s Rik Kirkland conducted a series of interviews in January at the World Economic Forum’s annual meeting in Davos. Among those interviewed were two leading business academics—Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee, coauthors of The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies (W. W. Norton, January 2014)—and two leading entrepreneurs: Anthony Goldbloom, the founder and CEO of Kaggle (the San Francisco start-up that’s crowdsourcing predictive-analysis contests to help companies and researchers gain insights from big data); and data scientist Jeremy Howard. This edited transcript captures and combines highlights from those conversations.

The Second Machine Age

What is it and why does it matter?

Andrew McAfee: The Industrial Revolution was when humans overcame the limitations of our muscle power. We’re now in the early stages of doing the same thing to our mental capacity—infinitely multiplying it by virtue of digital technologies. There are two discontinuous changes that will stick in historians’ minds. The first is the development of artificial intelligence, and the kinds of things we’ve seen so far are the warm-up act for what’s to come. The second big deal is the global interconnection of the world’s population, billions of people who are not only becoming consumers but also joining the global pool of innovative talent.

Erik Brynjolfsson: The First Machine Age was about power systems and the ability to move large amounts of mass. The Second Machine Age is much more about automating and augmenting mental power and cognitive work. Humans were largely complements for the machines of the First Machine Age. In the Second Machine Age, it’s not so clear whether humans will be complements or machines will largely substitute for humans; we see examples of both. That potentially has some very different effects on employment, on incomes, on wages, and on the types of companies that are going to be successful.

Video

Putting artificial intelligence to work: An interview with Anthony Goldbloom and Jeremy Howard

Machine-learning experts Anthony Goldbloom and Jeremy Howard tell McKinsey’s Rik Kirkland how smart machines will impact employment.

Jeremy Howard: Today, machine-learning algorithms are actually as good as or better than humans at many things that we think of as being uniquely human capabilities. People whose job is to take boxes of legal documents and figure out which ones are discoverable— that job is rapidly disappearing because computers are much faster and better than people at it.

In 2012, a team of four expert pathologists looked through thousands of breast-cancer screening images, and identified the areas of what’s called mitosis, the areas which were the most active parts of a tumor. It takes four pathologists to do that because any two only agree with each other 50 percent of the time. It’s that hard to look at these images; there’s so much complexity. So they then took this kind of consensus of experts and fed those breast-cancer images with those tags to a machine-learning algorithm. The algorithm came back with something that agreed with the pathologists 60 percent of the time, so it is more accurate at identifying the very thing that these pathologists were trained for years to do. And this machine-learning algorithm was built by people with no background in life sciences at all. These are total domain newbies.

Andrew McAfee: We thought we knew, after a few decades of experience with computers and information technology, the comparative advantages of human and digital labor. But just in the past few years, we have seen astonishing progress. A digital brain can now drive a car down a street and not hit anything or hurt anyone—that’s a high-stakes exercise in pattern matching involving lots of different kinds of data and a constantly changing environment.

Why now?

Computers have been around for more than 50 years. Why is machine learning suddenly so important?

Erik Brynjolfsson: It’s been said that the greatest failing of the human mind is the inability to understand the exponential function. Daniela Rus—the chair of the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Lab at MIT—thinks that, if anything, our projections about how rapidly machine learning will become mainstream are too pessimistic. It’ll happen even faster. And that’s the way it works with exponential trends: they’re slower than we expect, then they catch us off guard and soar ahead.

Andrew McAfee: There’s a passage from a Hemingway novel about a man going broke in two ways: “gradually and then suddenly.” And that characterizes the progress of digital technologies. It was really slow and gradual and then, boom—suddenly, it’s right now.

Jeremy Howard: The difference here is each thing builds on each other thing. The data and the computational capability are increasing exponentially, and the more data you give these deep-learning networks and the more computational capability you give them, the better the result becomes because the results of previous machine-learning exercises can be fed back into the algorithms. That means each layer becomes a foundation for the next layer of machine learning, and the whole thing scales in a multiplicative way every year. There’s no reason to believe that has a limit.

Erik Brynjolfsson: With the foundational layers we now have in place, you can take a prior innovation and augment it to create something new. This is very different from the common idea that innovations get used up like low-hanging fruit. Now each innovation actually adds to our stock of building blocks and allows us to do new things.

One of my students, for example, built an app on Facebook. It took him about three weeks to build, and within a few months the app had reached 1.3 million users. He was able to do that with no particularly special skills and no company infrastructure, because he was building it on top of an existing platform, Facebook, which of course is built on the web, which is built on the Internet. Each of the prior innovations provided building blocks for new innovations. I think it’s no accident that so many of today’s innovators are younger than innovators were a generation ago; it’s so much easier to build on things that are preexisting.

Jeremy Howard: I think people are massively underestimating the impact, on both their organizations and on society, of the combination of data plus modern analytical techniques. The reason for that is very clear: these techniques are growing exponentially in capability, and the human brain just can’t conceive of that.

There is no organization that shouldn’t be thinking about leveraging these approaches, because either you do—in which case you’ll probably surpass the competition—or somebody else will. And by the time the competition has learned to leverage data really effectively, it’s probably going to be too late for you to try to catch up. Your competitors will be on the exponential path, and you’ll still be on that linear path.

Let me give you an example. Google announced last month that it had just completed mapping the exact location of every business, every household, and every street number in the entirety of France. You’d think it would have needed to send a team of 100 people out to each suburb and district to go around with a GPS and that the whole thing would take maybe a year, right? In fact, it took Google one hour.

Now, how did the company do that? Rather than programming a computer yourself to do something, with machine learning you give it some examples and it kind of figures out the rest. So Google took its street-view database—hundreds of millions of images—and had somebody manually go through a few hundred and circle the street numbers in them. Then Google fed that to a machine-learning algorithm and said, “You figure out what’s unique about those circled things, find them in the other 100 million images, and then read the numbers that you find.” That’s what took one hour. So when you switch from a traditional to a machine-learning way of doing things, you increase productivity and scalability by so many orders of magnitude that the nature of the challenges your organization faces totally changes.

The senior-executive role

How will top managers go about their day-to-day jobs?

Andrew McAfee: The First Machine Age really led to the art and science and practice of management—to management as a discipline. As we expanded these big organizations, factories, and railways, we had to create organizations to oversee that very complicated infrastructure. We had to invent what management was.

In the Second Machine Age, there are going to be equally big changes to the art of running an organization.

I can’t think of a corner of the business world (or a discipline within it) that is immune to the astonishing technological progress we’re seeing. That clearly includes being at the top of a large global enterprise.

I don’t think this means that everything those leaders do right now becomes irrelevant. I’ve still never seen a piece of technology that could negotiate effectively. Or motivate and lead a team. Or figure out what’s going on in a rich social situation or what motivates people and how you get them to move in the direction you want.

These are human abilities. They’re going to stick around. But if the people currently running large enterprises think there’s nothing about the technology revolution that’s going to affect them, I think they would be naïve.

So the role of a senior manager in a deeply data-driven world is going to shift. I think the job is going to be to figure out, “Where do I actually add value and where should I get out of the way and go where the data take me?” That’s going to mean a very deep rethinking of the idea of the managerial “gut,” or intuition.

It’s striking how little data you need before you would want to switch over and start being data driven instead of intuition driven. Right now, there are a lot of leaders of organizations who say, “Of course I’m data driven. I take the data and I use that as an input to my final decision-making process.” But there’s a lot of research showing that, in general, this leads to a worse outcome than if you rely purely on the data. Now, there are a ton of wrinkles here. But on average, if you second-guess what the data tell you, you tend to have worse results. And it’s very painful—especially for experienced, successful people—to walk away quickly from the idea that there’s something inherently magical or unsurpassable about our particular intuition.

Jeremy Howard: Top executives get where they are because they are really, really good at what they do. And these executives trust the people around them because they are also good at what they do and because of their domain expertise. Unfortunately, this now saddles executives with a real difficulty, which is how to become data driven when your entire culture is built, by definition, on domain expertise. Everybody who is a domain expert, everybody who is running an organization or serves on a senior-executive team, really believes in their capability and for good reason—it got them there. But in a sense, you are suffering from survivor bias, right?

You got there because you’re successful, and you’re successful because you got there. You are going to underestimate, fundamentally, the importance of data. The only way to understand data is to look at these data-driven companies like Facebook and Netflix and Amazon and Google and say, “OK, you know, I can see that’s a different way of running an organization.” It is certainly not the case that domain expertise is suddenly redundant. But data expertise is at least as important and will become exponentially more important. So this is the trick. Data will tell you what’s really going on, whereas domain expertise will always bias you toward the status quo, and that makes it very hard to keep up with these disruptions.

Erik Brynjolfsson: Pablo Picasso once made a great observation. He said, “Computers are useless. They can only give you answers.” I think he was half right. It’s true they give you answers—but that’s not useless; that has some value. What he was stressing was the importance of being able to ask the right questions, and that skill is going to be very important going forward and will require not just technical skills but also some domain knowledge of what your customers are demanding, even if they don’t know it. This combination of technical skills and domain knowledge is the sweet spot going forward.

Anthony Goldbloom: Two pieces are required to be able to do a really good job in solving a machine-learning problem. The first is somebody who knows what problem to solve and can identify the data sets that might be useful in solving it. Once you get to that point, the best thing you can possibly do is to get rid of the domain expert who comes with preconceptions about what are the interesting correlations or relationships in the data and to bring in somebody who’s really good at drawing signals out of data.

The oil-and-gas industry, for instance, has incredibly rich data sources. As they’re drilling, a lot of their drill bits have sensors that follow the drill bit. And somewhere between every 2 and 15 inches, they’re collecting data on the rock that the drill bit is passing through. They also have seismic data, where they shoot sound waves down into the rock and, based on the time it takes for those sound waves to be captured by a recorder, they can get a sense for what’s under the earth. Now these are incredibly rich and complex data sets and, at the moment, they’ve been mostly manually interpreted. And when you manually interpret what comes off a sensor on a drill bit or a seismic survey, you miss a lot of the richness that a machine-learning algorithm can pick up.

Andrew McAfee: The better you get at doing lots of iterations and lots of experimentation—each perhaps pretty small, each perhaps pretty low-risk and incremental—the more it all adds up over time. But the pilot programs in big enterprises seem to be very precisely engineered never to fail—and to demonstrate the brilliance of the person who had the idea in the first place.

That makes for very shaky edifices, even though they’re designed to not fall apart. By contrast, when you look at what truly innovative companies are doing, they’re asking, “How do I falsify my hypothesis? How do I bang on this idea really hard and actually see if it’s any good?” When you look at a lot of the brilliant web companies, they do hundreds or thousands of experiments a day. It’s easy because they’ve got this test platform called the website. And they can do subtle changes and watch them add up over time.

So one of the implications of the manifested brilliance of the crowd applies to that ancient head-scratcher in economics: what the boundary of the firm should be. What should I be doing myself versus what should I be outsourcing? And, now, what should I be crowdsourcing?

Implications for talent and hiring

It’s important to make sure that the organization has the right skills.

Jeremy Howard: Here’s how Google does HR. It has a unit called the human performance analytics group, which takes data about the performance of all of its employees and what interview questions were they asked, where was their office, how was that part of the organization’s structure, and so forth. Then it runs data analytics to figure out what interview methods work best and what career paths are the most successful.

Anthony Goldbloom: One huge limitation that we see with traditional Fortune 500 companies—and maybe this seems like a facile example, but I think it’s more profound than it seems at first glance—is that they have very rigid pay scales.

And they’re competing with Google, which is willing to pay $5 million a year to somebody who’s really great at building algorithms. The more rigid pay scales at traditional companies don’t allow them to do that, and that’s irrational because the return on investment on a $5 million, incredibly capable data scientist is huge. The traditional Fortune 500 companies are always saying they can’t hire anyone. Well, one reason is they’re not willing to pay what a great data scientist can be paid elsewhere. Not that it’s just about money; the best data scientists are also motivated by interesting problems and, probably most important, by the idea of working with other brilliant people.

Machine learning and computers aren’t terribly good at creative thinking, so the idea that the rewards of most jobs and people will be based on their ability to think creatively is probably right.

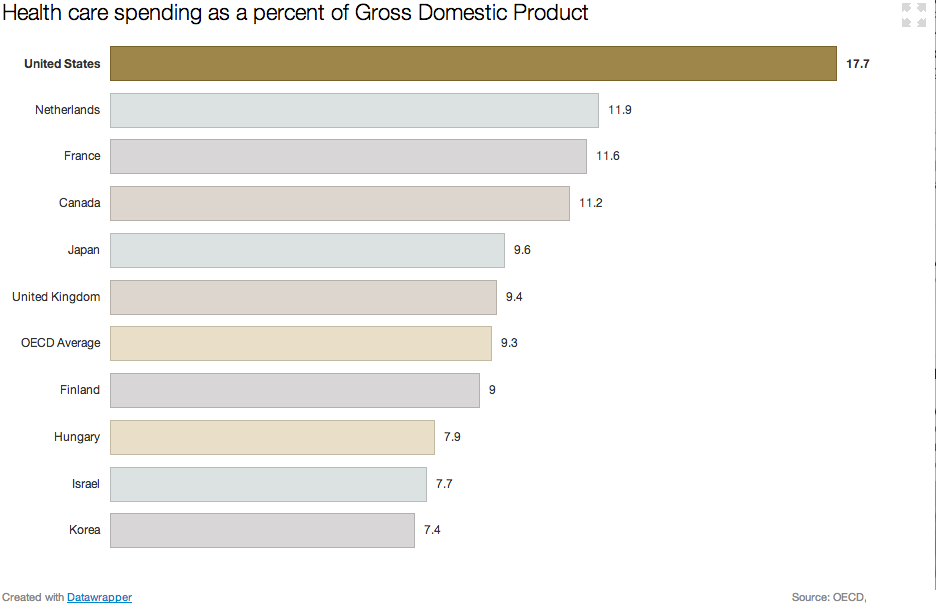

/cdn3.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/692516/Data_plot.0.png)

/cdn2.vox-cdn.com/assets/4826288/medicare_per_person.png)

/cdn2.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/679852/helath_growth.0.png)