Solid report on personal health data. Interesting observation re. (lack of) alignment between research and business objectives… i.e. public vs private goods?

http://www.rwjf.org/en/research-publications/find-rwjf-research/2014/03/personal-data-for-the-public-good.html

Report: http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/reports/2014/rwjf411080

PDF:

1. Executive Summary

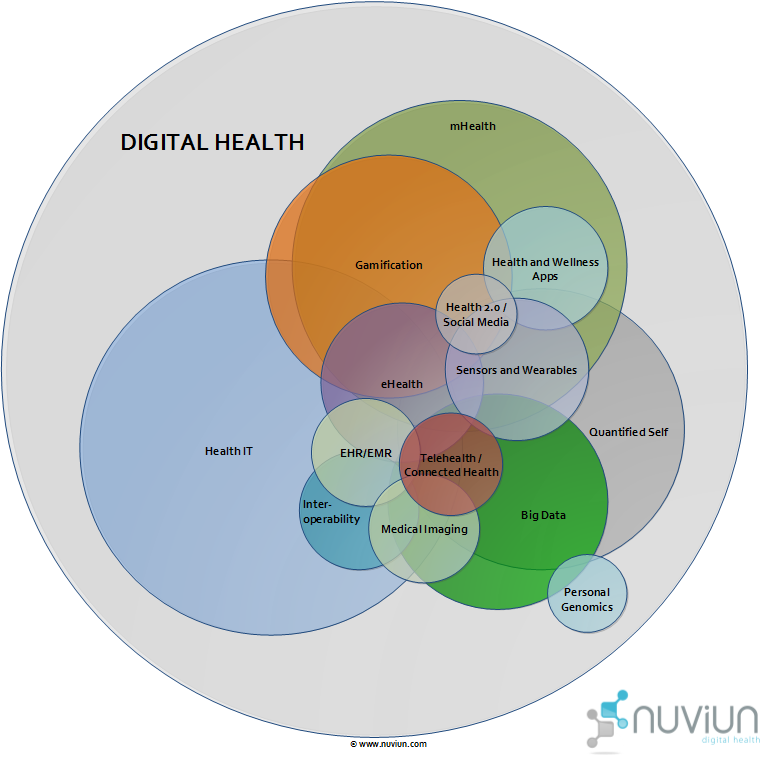

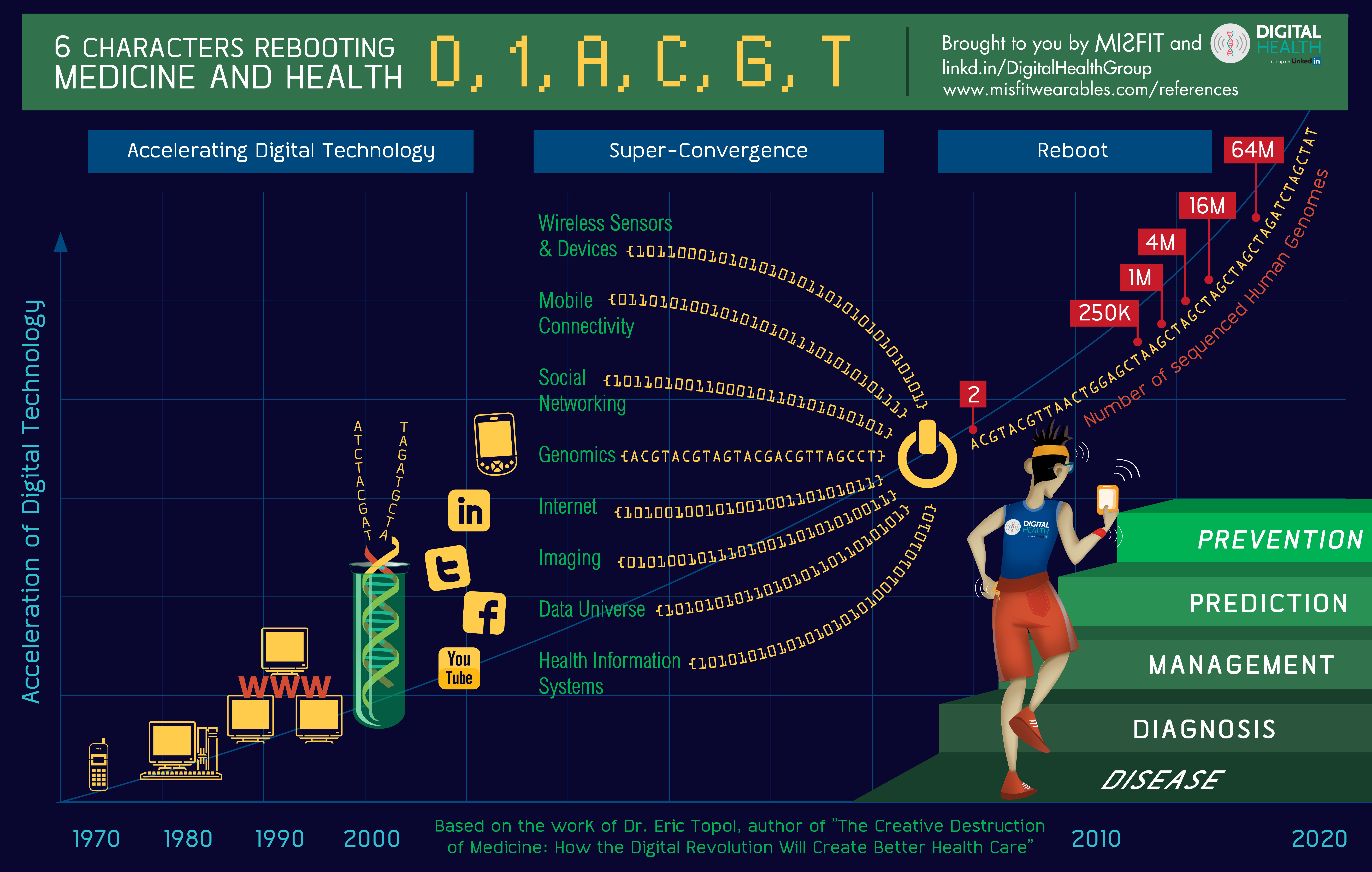

Individuals are tracking a variety of health-related data via a growing number of wearable devices and smartphone apps. More and more data relevant to health are also being captured passively as people communicate with one another on social networks, shop, work, or do any number of activities that leave “digital footprints.”

Almost all of these forms of “personal health data” (PHD) are outside of the mainstream of traditional health care, public health or health research. Medical, behavioral, social and public health research still largely rely on traditional sources of health data such as those collected in clinical trials, sifting through electronic medical records, or conducting periodic surveys.

Self-tracking data can provide better measures of everyday behavior and lifestyle and can fill in gaps in more traditional clinical data collection, giving us a more complete picture of health. With support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the Health Data Exploration (HDE) project conducted a study to better understand the barriers to using personal health data in research from the individuals who track the data about their own personal health, the companies that market self-tracking devices, apps or services and aggregate and manage that data, and the researchers who might use the data as part of their research.

Perspectives

Through a series of interviews and surveys, we discovered strong interest in contributing and using PHD for research. It should be noted that, because our goal was to access individuals and researchers who are already generating or using digital self-tracking data, there was some bias in our survey findings—participants tended to have more education and higher household incomes than the general population. Our survey also drew slightly more white and Asian participants and more female participants than in the general population.

Individuals were very willing to share their self-tracking data for research, in particular if they knew the data would advance knowledge in the fields related to PHD such as public health, health care, computer science and social and behavioral science. Most expressed an explicit desire to have their information shared anonymously and we discovered a wide range of thoughts and concerns regarding thoughts over privacy.

Equally, researchers were generally enthusiastic about the potential for using self-tracking data in their research. Researchers see value in these kinds of data and think these data can answer important research questions. Many consider it to be of equal quality and importance to data from existing high quality clinical or public health data sources.

Companies operating in this space noted that advancing research was a worthy goal but not their primary business concern. Many companies expressed interest in research conducted outside of their company that would validate the utility of their device or application but noted the critical importance of maintaining their customer relationships. A number were open to data sharing with academics but noted the slow pace and administrative burden of working with universities as a challenge.

In addition to this considerable enthusiasm, it seems a new PHD research ecosystem may well be emerging. Forty-six percent of the researchers who participated in the study have already used self-tracking data in their research, and 23 percent of the researchers have already collaborated with application, device, or social media companies.

The Personal Health Data Research Ecosystem

A great deal of experimentation with PHD is taking place. Some individuals are experimenting with personal data stores or sharing their data directly with researchers in a small set of clinical experiments. Some researchers have secured one-off access to unique data sets for analysis. A small number of companies, primarily those with more of a health research focus, are working with others to develop data commons to regularize data sharing with the public and researchers.

SmallStepsLab serves as an intermediary between Fitbit, a data rich company, and academic researchers via a “preferred status” API held by the company. Researchers pay SmallStepsLab for this access as well as other enhancements that they might want.

These promising early examples foreshadow a much larger set of activities with the potential to transform how research is conducted in medicine, public health and the social and behavioral sciences.

Opportunities and Obstacles

There is still work to be done to enhance the potential to generate knowledge out of personal health data:

•

Privacy and Data Ownership: Among individuals surveyed, the dominant condition (57%) for making their PHD available for research was an assurance of privacy for their data, and over 90% of respondents said that it was important that the data be anonymous. Further, while some didn’t care who owned the data they generate, a clear majority wanted to own or at least share ownership of the data with the company that collected it.

•

Informed Consent: Researchers are concerned about the privacy of PHD as well as respecting the rights of those who provide it. For most of our researchers, this came down to a straightforward question of whether there is informed consent. Our research found that current methods of informed consent are challenged by the ways PHD are being used and reused in research. A variety of new approaches to informed consent are being evaluated and this area is ripe for guidance to assure optimal outcomes for all stakeholders.

•

Data Sharing and Access: Among individuals, there is growing interest in, as well as willingness and opportunity to, share personal health data with others. People now share these data with others with similar medical conditions in online groups like PatientsLikeMe or Crohnology, with the intention to learn as much as possible about mutual health concerns. Looking across our data, we find that individuals’ willingness to share is dependent on what data is shared, how the data will be used, who will have access to the data and when, what regulations and legal protections are in place, and the level of compensation or benefit (both personal and public).

•

Data Quality: Researchers highlighted concerns about the validity of PHD and lack of standardization of devices. While some of this may be addressed as the consumer health device, apps and services market matures, reaching the optimal outcome for researchers might benefit from strategic engagement of important stakeholder groups.

We are reaching a tipping point. More and more people are tracking their health, and there is a growing number of tracking apps and devices on the market with many more in development. There is overwhelming enthusiasm from individuals and researchers to use this data to better understand health. To maximize personal data for the public good, we must develop creative solutions that allow individual rights to be respected while providing access to high-quality and relevant PHD for research, that balance open science with intellectual property, and that enable productive and mutually beneficial collaborations between the private sector and the academic research community.