http://www.economist.com/news/international/21608767-patients-around-world-are-starting-give-doctors-piece-their-mind-result?fsrc=scn/tw_ec/docadvisor

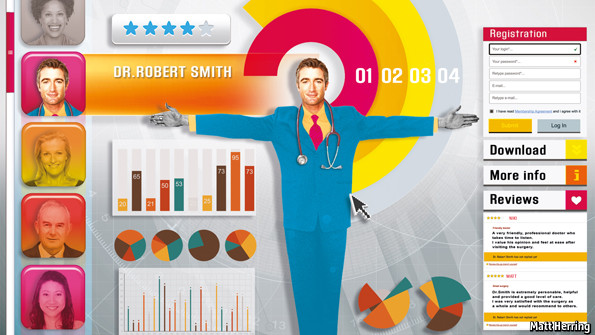

Patients’ reviews

DocAdvisor

Patients around the world are starting to give doctors a piece of their mind. The result should be better care

WHEN a patient in Illinois did not like the result of her breast-augmentation surgery, she reacted like many dissatisfied customers: by writing negative comments about her doctor on websites that feature such reviews. Her breasts, she said, looked like something out of a horror movie. Other unhappy patients joined her online, calling the doctor “dangerous”, “horrible” and a “jackass”. He sued them for defamation. (The cases were later dropped.)

Other doctors have filed similar lawsuits, mostly in America. Though few have won, their reaction illustrates a discomfort with patient reviews felt by many of their colleagues. Some question the accuracy and relevance of the feedback; others complain that privacy rules prevent them from responding. Sites often have just a handful of ratings per doctor, meaning results can be skewed by a single bad write-up.

But increasingly, doctors cannot afford to ignore them. They often lead the results of searches for doctors’ names. In America, the world’s biggest health-care market, firms that offer health insurance are making employees pay a bigger share, pushing them to search for guidance online. The most sophisticated sites are attracting more users by including reviews and other features. ZocDoc also lets patients make appointments. Offerings from Vitals include a quality indicator it has built using data from 170,000-odd sources. Castlight Health includes prices gathered from insurance bills and other data. The differences can be startling—the cost of a brain scan in Philadelphia ranges from $264 to $3,271.

With around 60 review sites, America leads the way. But they are also popping up in other countries where patients pay for at least part of their care. Practo, an Indian firm that schedules appointments with doctors, plans to start publishing patients’ reviews later this year. More and more Chinese patients, who generally do not have a regular family doctor, are using a site run by Hao Dai Fu (“good doctor”) to navigate their country’s unstructured health system, says Haijing Hao of the University of Massachusetts. It has profiles of around 300,000 doctors and over 1m reviews.

Increasingly, doctors, hospitals and health systems are seeking to turn the trend to their advantage. Some now offer incentives, such as prize draws, for patients to go online and rate them. A survey by ZocDoc found that 85% of doctors on its site looked at their ratings last year. And a handful of health-care providers have even started to publish reviews themselves. The University of Utah, which runs four hospitals and ten clinics, was one of the first, in 2012. Its doctors’ complaints about independent sites encouraged it to publish patient feedback that was already being collected for internal use. Some of its doctors now have hundreds of reviews.

Preparing staff for the publication of all the comments, good and bad, took a year, says Brian Gresh, who helped create the university’s system. But their worries appear to have been groundless: most reviews are positive, and patient-satisfaction scores improved after the move. Happy patients communicate and co-operate better with their doctors, says Tom Lee, the chief medical officer of Press Ganey, a firm that surveys patients on behalf of health-care providers, including for the University of Utah. Its boss, Pat Ryan, predicts that plenty of other hospitals will follow suit.

Some doctors are still sceptical, fearing, for example, that patients may judge a hospital on its decor rather than its care. But patients are rarely swayed much by such trivia, insists Mr Ryan: “If you have flat-screen televisions and your communication is poor, you will get very bad scores.” Moreover, the feedback reminds doctors that every meeting with a patient matters, so they try harder.

America’s government has started to link health-care payments with patient feedback: Medicare, a federal scheme for over-65s, recently started to give bonuses to hospitals that score well. The Cleveland Clinic, a big hospital, uses these data to improve its care. Britain’s National Health Service has surveyed patients for over a decade (though not on the performance of individual doctors) and published the results online—though some think it could use its findings better.

But many other governments do not even ask patients for their opinions. German doctors and hospitals, for example, have fought efforts to link funding with quality of care, says Maria Nadj-Kittler of the Picker Institute Europe, a research organisation, and are therefore hostile to patient reviews. This is a missed opportunity. Patients who hold their doctors accountable make them better and more efficient. That is good news no matter who pays.

Rebecca Hobson | Thu, 3 Jul 2014 12:17 pm

Great, thought provoking piece – but I’m not sure I agree. I imagine there’ll be stringent measures in place around any corporate sponsorship of public health messaging, and effectively, these brands will end up subsiding PHE – which it badly needs? Also, if PHE puts out a message saying ‘drink only one can of pop a day’, say, won’t it be more powerful if it’s sponsored by the pop brand itself? Ppl are far more likely to listen to Pepsi than the government.

Unsuitable or offensive? Report this comment