- From this HBR article

- strategic thinking is seen as a universally important skill

- it about being able to see, predict, and plan ahead

- “Strategic leaders take a broad, long-range approach to problem-solving and decision-making that involves objective analysis, thinking ahead, and planning. That means being able to think in multiple time frames, identifying what they are trying to accomplish over time and what has to happen now, in six months, in a year, in three years, to get there,” he writes. “It also means thinking systemically. That is, identifying the impact of their decisions on various segments of the organization–including internal departments, personnel, suppliers, and customers.“

- It’s also important to pass strategic thinking onto employees

- One of the key prerequisites of strategic leadership is having relevant and broad business information that helps leaders elevate their thinking beyond the day-to-day

- need to communicate a well-articulated philosophy, a mission statement, and achievable goals throughout your company

- Whenever possible, try to promote foresight and long-term thinking

- promote a “future perspective” in your company. If a manager suggests a course of action, you need to him or her ask two questions: First, what underlying strategic goal does this action serve, and why? And second, what kind of impact will this have on internal and external stakeholders? “Consistently asking these two questions whenever action is considered will go a long way towards developing strategic leaders,” he writes.

http://www.inc.com/will-yakowicz/how-to-foster-strategic-thinking-in-employees.html

How to Get Your Employees to Think Strategically BY WILL YAKOWICZ

Studies show that strategic thinking is the most important element of leadership. But how do you instill the trait in others at your company?

What leadership skill do your employees, colleagues, and peers view as the most important for you to have? According Robert Kabacoff, the vice president of research at Management Research Group, a company that creates business assessment tools, it’s the ability to plan strategically.

He has research to back it up: In the Harvard Business Review, he cites a 2013 study by his company in which 97 percent of a group of 10,000 senior executives said strategic thinking is the most critical leadership skill for an organization’s success. In another study, he writes, 60,000 managers and executives in more than 140 countries rated a strategic approach to leadership as more effective than other attributes including innovation, persuasion, communication, and results orientation.

But what’s so great about strategic thinking? Kabacoff says that as a skill, it’s all about being able to see, predict, and plan ahead: “Strategic leaders take a broad, long-range approach to problem-solving and decision-making that involves objective analysis, thinking ahead, and planning. That means being able to think in multiple time frames, identifying what they are trying to accomplish over time and what has to happen now, in six months, in a year, in three years, to get there,” he writes. “It also means thinking systemically. That is, identifying the impact of their decisions on various segments of the organization–including internal departments, personnel, suppliers, and customers.”

As a leader, you also need to pass strategic thinking to your employees, Kabacoff says. He suggests instilling the skill in your best managers first, and they will help pass it along to other natural leaders within your company’s ranks. Below, read his five tips for how to carry out this process.

Dish out information.

Kabacoff says that you need to encourage managers to set aside time to thinking strategically until it becomes part of their job. He suggests you provide them with information on your company’s market, industry, customers, competitors, and emerging technologies. “One of the key prerequisites of strategic leadership is having relevant and broad business information that helps leaders elevate their thinking beyond the day-to-day,” he writes.

Create a mentor program.

Every manager in your company should have a mentor. “One of the most effective ways to develop your strategic skills is to be mentored by someone who is highly strategic,” Kabacoff says. “The ideal mentor is someone who is widely known for his/her ability to keep people focused on strategic objectives and the impact of their actions.”

Create a philosophy.

As the leader, you need to communicate a well-articulated philosophy, a mission statement, and achievable goals throughout your company. “Individuals and groups need to understand the broader organizational strategy in order to stay focused and incorporate it into their own plans and strategies,” Kabacoff writes.

Reward thinking, not reaction.

Whenever possible, try to promote foresight and long-term thinking. Kabacoff says you should reward your managers for the “evidence of thinking, not just reacting,” and for “being able to quickly generate several solutions to a given problem and identifying the solution with the greatest long-term benefit for the organization.”

Ask “why” and “when.”

Kabacoff says you need to promote a “future perspective” in your company. If a manager suggests a course of action, you need to him or her ask two questions: First, what underlying strategic goal does this action serve, and why? And second, what kind of impact will this have on internal and external stakeholders? “Consistently asking these two questions whenever action is considered will go a long way towards developing strategic leaders,” he writes.

David Ryder/Getty ImagesJeffrey P. Bezos, the founder of Amazon.com.

David Ryder/Getty ImagesJeffrey P. Bezos, the founder of Amazon.com.

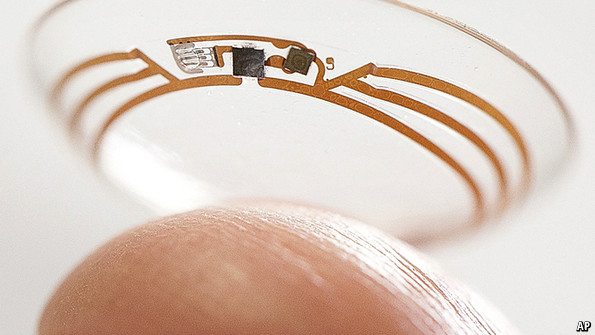

Smartphone app visualises two similar running routesI am obsessed with my running app. Last week obsession became frustration verging on throw-the-phone-on-the-floor anger. Wednesday’s lunchtime 5km run was pretty good, almost back up to pre-Christmas pace. On Friday, I thought I had smashed it. The first 2km were very close to my perennial 5 min/km barrier. And I was pretty sure I had kept up the pace. But the app disagreed.As I ate my 347 calorie salad – simultaneously musing on how French dressing could make up 144 of them – I switched furiously between the two running route analyses. This was just preposterous; the GPS signal must have been confused; I must have been held up overtaking that tourist group for longer than I realised; or perhaps the app is just useless and all previous improvements in pace were bogus.My desire to count stuff is easy to poke fun at. It’s probably pretty unhealthy too. But it’s only going to be encouraged over the next few years. Wearable technology is here to stay. Smart phone cameras

Smartphone app visualises two similar running routesI am obsessed with my running app. Last week obsession became frustration verging on throw-the-phone-on-the-floor anger. Wednesday’s lunchtime 5km run was pretty good, almost back up to pre-Christmas pace. On Friday, I thought I had smashed it. The first 2km were very close to my perennial 5 min/km barrier. And I was pretty sure I had kept up the pace. But the app disagreed.As I ate my 347 calorie salad – simultaneously musing on how French dressing could make up 144 of them – I switched furiously between the two running route analyses. This was just preposterous; the GPS signal must have been confused; I must have been held up overtaking that tourist group for longer than I realised; or perhaps the app is just useless and all previous improvements in pace were bogus.My desire to count stuff is easy to poke fun at. It’s probably pretty unhealthy too. But it’s only going to be encouraged over the next few years. Wearable technology is here to stay. Smart phone cameras

Keeping an eye on glucose levels

Keeping an eye on glucose levels