They are motivated by a need to rein in health care costs, which continue to rise faster than overall inflation, but the federal health care law is also changing how some view their obligations to their employees.

Some major firms, like Walgreen, the drugstore chain, are giving those who qualify money to buy insurance on a private health exchange. Aon Hewitt, a benefits consultant that will oversee health plans on Walgreen’s behalf, said 18 large employers had signed up so far, including Sears and Darden Restaurants.

But here in Cincinnati, General Electric is taking the opposite approach.

One of the largest employers in the nation, it spends more than $2 billion a year offering coverage to 500,000 employees and retirees and their families. And it is using its considerable clout in places like this — where its giant aviation business gives it a major presence — to work directly with doctors and hospitals to improve care and reduce costs.

“I don’t know anybody who isn’t trying almost everything,” said Helen Darling, president of the National Business Group on Health, which represents employers providing benefits. “We’re going to see a lot of activity in the next couple of years.”

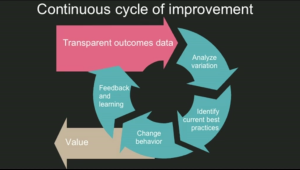

Over the last few years, G.E. has pushed for the creation of so-called medical homes, in which an individual medical practice closely coordinates a patient’s care by having access to all of the patient’s medical records.

In Cincinnati, about 118 doctors’ practices have converted to medical homes, and all five of the major health systems are making their primary care practices move in that direction. G.E. has also pushed for greater transparency of results.

“If we don’t take accountability ourselves for figuring this out, we’re part of the problem,” said Sue Siegel, a senior executive at G.E., who sees transformation of health care both as a business opportunity and a business necessity.

“We have to be involved in the solution,” she said. “We can’t just wait for someone to tell us that it is going to be fixed.”

What distinguishes the effort by G.E. is its direct focus on hospitals and doctors. Companies looking to the private exchanges are largely hoping to save money and want to be freed from the headache of administering health benefits.

In Walgreen’s case, the company says it doesn’t plan to lower its share of its workers’ health care costs but hopes to foster more competition among insurers, leading to better prices and more choice for employees.

In Cincinnati, G.E. took on both a cheerleading and coordinating role. In early 2010, Jeffrey R. Immelt, its chief executive, addressed local business leaders and urged them to think strategically and align their efforts to make more of a difference. There were already significant efforts under way to foster medical homes, for example, and G.E. pushed to find more financing to expand the concept to more medical practices and keep the focus on that initiative.

“The ever-present vigilance of the employers help nudge things along,” said Craig Brammer, chief executive of three area health care coalitions, including the Greater Cincinnati Health Council, which is made up of the area’s hospitals, health plans and employers.

The city’s health systems say they recognize that insurers and employers are increasingly going to reward them for better tracking their patients in and out of the hospital. “We are clearly gearing up to change directions from fee for service for what I’ll call payment for value,” said Will Groneman, an executive vice president for TriHealth, one of the systems.

The medical home also appears to resonate with employees. When Mary Farris, a 44-year-old marketing executive for G.E., found herself going to a local urgent care center because she could never get an appointment with her physician, she switched to a practice that had become a medical home.

What strikes Ms. Farris was how much time the doctor and medical assistant spent gathering her medical history and making sure there weren’t additional medical issues. While she came in for a spider bite, the focus was on her well-being as a working mother whose father was seriously ill at the time. “The picture was more on all of me as opposed to one isolated incident,” she said. “Somebody was trying to connect the dots.”

In Cincinnati, there are beginning to be grudging signs of success. Early results are promising: patients enrolled in medical homes had 3.5 percent fewer visits to the emergency room and 14 percent fewer hospital admissions over the four years from 2008 through 2012. G.E. plans to ask an outside firm to do a more detailed analysis.

But employers looking to adapt a similar strategy will find “it’s hard to do,” said David Lansky, the chief executive of the Pacific Business Group on Health, which represents West Coast employers. While “the opportunity is significant,” he said, companies may not have the time or resources to work in too many of their locations, with different hospitals and health plans in each market.

Some companies — Trader Joe’s for example — decided to send at least some employees to the new public exchanges. Trader Joe’s has left coverage for three-quarters of its work force untouched but is giving part-time workers a contribution of $500 to buy policies in the newly created state marketplaces. Because of the employees’ low incomes, the company says it believes many will be eligible for federal subsidies to help them afford coverage.

But a few major employers are taking even more aggressive stances and are trying to reshape how health care is delivered in this country.

They are increasingly looking to make direct connections with health systems, particularly well-regarded institutions that can deliver good care for what can be very expensive back or heart problems. G.E. recently signed an agreement with Hospital for Special Surgery in New York, a high-volume orthopedic hospital, to oversee the care of some employees getting hip and knee replacements. Last year, Walmart contracted with health systems like the Cleveland Clinic, Mayo and Geisinger, among others, to take care of employees who need transplants, heart and spine care. The company says it will soon expand the program to other centers of excellence.

The decision doesn’t always sit well with the home team. In Cincinnati, the UC Health System, which includes an academic medical center that also serves the area’s major source of care for the uninsured, says it would welcome a similar opportunity to provide joint replacements for G.E., but executives say they simply cannot afford to offer significant discounts. “We don’t have the resources to cut deals,” said Dr. Myles Pensak, an executive for UC Health.

G.E. is unapologetic. The company says it will continue to try a variety of approaches until it finds a way to tame health care costs even more than the annual growth rate achieved so far of under 3 percent. “You’ll see many, many experiments across the board,” Ms. Seigel said.