Nice and punchy oped on low value care…

https://www.mja.com.au/insight/2014/34/richard-king-what-not-do

Nice and punchy oped on low value care…

https://www.mja.com.au/insight/2014/34/richard-king-what-not-do

http://blogs.crikey.com.au/croakey/2014/09/09/outsourcing-medicare-is-it-as-easy-as-%CF%80/

Following on from the range of issues raised by Croakey contributors about the outsourcing of MBS and PBS payments, Margaret Faux discusses the most appropriate role for the private sector in supporting core government functions and the risks involved when private sector interests conflict with the central role of government. She writes:

In a U.S managed care styled initiative, private insurers have been given the right to tender to manage the operation of the government’s new Primary Health Networks, which will soon replace existing Medicare Locals. And recently, the government’s expression of interest from the private sector to provide outsourced claims and payment services for the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Schedule (PBS) was closed.

There’s nothing new or surprising about governments outsourcing service provision to the private sector. Recognising that key policy issues can sometimes be better addressed by tapping into private sector innovation and expertise is an important role of government. But when outsourcing amounts to the abrogation of core functions of the state, the inherent risks can be high.

The commission of audit recommendation to outsource MBS and PBS payment processing suggested that outsourcing these payments was a potentially high risk undertaking and specifically warned against outsourcing the assessment of entitlements. The problem however is that almost all MBS claims require assessment of entitlements. And given that there is not yet one third party payer of medical claims in Australia who has successfully mastered the complexity of this work, the prospect of outsourcing it tocontenders such as banks, Australia Post or even the private health insurers is cause for serious concern.

The business of paying for medical services in Australia – whether related to workers compensation, third party matters, the public or private provision of services, veterans entitlements, consultations at the GP or a specialist, in or out of hospital or anywhere else – takes place across an astonishingly fragmented industry in which each third party payer has its own requirements, rules, procedures and fees. Some private health insurers even pay different rates in different states.

But of all of these payers, the most effective, efficient and accurate in terms of the core business of processing and paying claims, is Medicare. This is a basic and undeniable truth accepted by those who interact daily with all payers in the medical billing industry. So it is interesting that rather than outsourcing areas in which Medicare struggles, such as claim adjustments, complex claim assessments, provider liaison and MBS interpretations, the government has instead chosen to seek expressions of interest in the one area in which Medicare excels.

In 1973 the architects of the original Medibank Scheme, Scotton and Deeble, understood very well the importance of having a separate department to manage the complexities of medical claims processing.

“In the fragile chain of decisions on which the successful implementation of Medibank hung, the decision to establish the Health Insurance Commission must have been one of the most critical.”1

The battle for an independent body of experts to administer the new national insurance scheme was hard fought and finally won when Bill Hayden agreed to the establishment of the Health Insurance Commission (HIC).

And this was long before private health fund schemes accessed the Medicare bucket of tax payer money, when there were approximately 5000 less Medicare services than there are today, well before some modern medical specialties had been thought of, before Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and Computerised Tomography (CT) scanning existed and at a time when the concept of Telehealth would have been considered science fiction.

But the HIC was dissolved in 2005 and with it went much needed expertise, and today no-one and no software has been able to conquer what is highly specialised and still largely manual work.

In order to consider the possible outcome of any future outsourcing of Medicare payments let us look at a frontline experience of the recent outsourcing of medical claims, which was undertaken by the Department of Defence. In 2012 government processing of Australian Defence Force (ADF) medical claims was outsourced to the private sector. In a four year $1.4 billion deal, a contract was awarded toGarrison Health Services (a business arm of Medibank Health Solutions) to provide a national, integrated solution which included the processing of ADF personnel medical claims.

Conceptualising the process was easy, however the execution was not.

Midway through 2013 many billers noticed that ADF claims, which had previously been processed without too much fuss, were not being paid. The 90 day arrears on these claims had reached unacceptable levels as had practitioner complaints. Numerous calls and enquiries later, one medical billing company had almost $100,000 worth of ADF claims returned indicating there was a new arrangement and advising that the claims should be redirected to Medibank Private as part of a new government outsource initiative.

But after redirecting the claims as instructed, they were again returned as no-one at Medibank knew anything about them. Some months later, advice was received indicating that a new branch within Medibank had taken over the role, but that before any claims could be paid, every doctor first had to register, by signing a new form. Hundreds of signed forms later the claims were rejected again, this time because the amounts were considered incorrect. ADF claims had always been paid at the AMA rates (for as many years as memory serves) but apparently a unilateral decision had been made to instead apply Medibank’s no-gap rates, which are significantly lower. It was then of course only a matter of time before the medical profession would protest against the resultant 27% reduction in remuneration, which had been imposed without consultation.

After reprocessing hundreds of claims for the third time, the first payments started to trickle in, though the anticipated calls from doctors enquiring as to why the fees they were receiving were below the AMA rates were not far behind. Within weeks a full blown dispute had erupted between the payer and one group of doctors, while others had started requiring ADF personnel to pay their medical bills at the point of service, informing them that they should sort out their reimbursements themselves. The official letters came next, in which doctors were reminded of the legal barrier which prevented them from requiring ADF personnel to pay for medical services. It fell on deaf ears.

In subsequent advice it appeared that Garrison had changed its process yet again by adopting its own new fee schedule and that no further accounts would be paid without the correct new fees, as well as the inclusion of the defence approval number (DAN), to which the EP ID number (an unexplained extra piece of data) was later added – two additional pieces of data for the one soldier were considered better than one. Many DAN inclusive but EP exclusive rejected claims later, it was discovered that the mysterious EP was apparently unknown to anyone – neither clinicians nor hospital account administrators. But with a steely resolve and tenacious spirit EPs were finally tracked down and claims could be submitted again. However one must note here that it takes on average an hour on the phone to obtain the DAN and EP for each ADF claim.

As at today, ADF claims continue to be a significant cause of patient and doctor complaints, which has escalated to a point where some doctors are considering whether they may exclude ADF personnel from their practices altogether – patients always come off worse in these scenarios. The process is manual, labour intensive, slow and from the point of view of integration and efficiency, an abject failure. It was far simpler and much more efficient before it was outsourced.

Because profit will often usurp clinical outcomes as the main priority in private sector participation in health, the potential risks of the proposed outsourcing of management of the new Primary Health Networks is also apparent. In fact corporate involvement in general practice has long been identified as an area of concern, and one which has contributed to increased health spending, for which individual doctors are sometimes blamed.

Since 2006 the Professional Services Review Scheme (PSR), whose objective is to protect the public interest in the standard of MBS and PBS services, has commented that the corporatisation of medical practices is a contributor to inappropriate and excessive MBS claiming by doctors. Having signed contracts binding them to daily, weekly and monthly targets (both in terms of the number of patients seen and the types of services provided) doctors have reported feeling pressured to reconcile targets with real patients. It is not uncommon for doctors working in these corporate practices to end up in front of the PSR where their MBS claiming behaviour comes under review. And due to regulatory limitations, the corporation itself will rarely be held to account.

Our current workers compensation system (which is managed care by another name) provides another example, as well as important evidence, of the potential poor health outcomes and increased costs that can result when care is managed outside of the doctor patient relationship, and is driven by private sector profits.

Outsourcing works best when the private sector is used to support core government activity. But when it is the core government activity that is outsourced, the private sector will inevitably find itself conflicted between profit and service.

While Aristotle might have outsourced the preparation of his meals by hiring a cook, he would never have outsourced geometry. He would rather have eaten an outsourced pie than outsource the discovery of π itself.

1. The Making of Medibank, RB Scotton and CR Macdonald, Australian Studies in Health Service Administration, No 76

Excellent summary of current US funding situation…

http://www.vox.com/2014/9/10/6121631/the-pay-less-get-more-era-of-health-care

The “pay less, get more” era of health care

Health care spending has, for decades, followed a consistent pattern. America pays more and more for health care — and gets less and less.

Between 1990 and 2012, the insured rate in the United States fell two percentage points, from 86.6 to 84.6 percent. If the insured rate had just held steady, six million more people would have been covered in 2012.

While we were covering less people, we kept spending more on health care. National health spending, over that time period, rose from 12 percent of the economy in 1990 to 17.2 percent in 2012. Adjusted for inflation, health-care spending rose from $1.1 trillion to $2.8 trillion over those 22 years.

/cdn3.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/692516/Data_plot.0.png)

That’s been the typical story of American health care: a lousy deal where we get less and spend more.

But there’s a growing body of evidence that this trend is changing; that we’re starting to get a shockingly better deal in a way that has giant consequences for how America spends money. Call it the “get more, pay less” era.

There are two big trends that, taken together, suggest we may be fundamentally different era of health care spending.

The first is lots more people getting coverage. This is mostly Obamacare: the health care law is expected to expand insurance coverage to 26 million people by 2024. In 2014 alone, most estimates suggest about 5 million people have gained health coverage through the law. The recovering economy is likely playing a supporting role, too, with those gaining jobs also gaining access to employer-sponsored coverage.

The second big trend is in what we spend: actuaries expect that health care costs will grow slower over the next decade than they did in the 1990s and 2000s.

More specifically: health care costs grew, on average, 2 percent faster than the economy between 1990 and 2008. Health spending took over an ever-growing share of the economy. Workers barely got raises; skyrocketing premiums ate up most of their additional wages.

The next decade is now expected to be different. Actuaries at the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services project health care costs to grow 1 percent faster than the rest of the economy between 2013 and 2023.

“We are seeing historic moderation in costs now over a considerable period of time,” Kaiser Family Foundation president Drew Altman says. HIs group recently released data showing slow growth of employer-sponsored coverage. “It’s absolutely true we’re seeing that and any expert will tell you that.”

This is startling: over the next decade, forecasters think our health spending will grow at a slower rate, even as millions and millions of Americans gain access to health insurance. After two decades of spending more and getting less, we’re entering an era of spending less and getting more. It’s bizarro health spending world.

One thing that’s so striking about the “get more, pay less” trend is that it isn’t limited to one particular insurance plan or program. It’s starting to crop up in lots of new health care data, suggesting this change has become pervasive in the health care industry.

Start with private health insurance: the Kaiser Family Foundation recently published research finding the average price of Obamacare’s benchmark will fall slightly in 2015. As my colleague Ezra Klein wrote recently, this just about unprecedented. “Falling is not a word that people associate with health-insurance premiums,” he writes .”They tend to rise as regularly as the morning sun.”

Lower premiums make health care dollars stretch further: Obamacare shoppers will be able to buy the coverage they had last year at a slightly lower price. That’s a big deal when you’re talking about paying for a health insurance program meant to cover tens of millions of Americans.

Increasingly narrow health insurance networks are another sign of “get more, pay less” era. Over the past few years — and especially under Obamacare —insurers have gravitated towards cheaper premium plans to offer access to a smaller number of doctors.

These plans’ more limited doctor choice can have a big impact on spending. Research from economists Jon Gruber and Robin McKnight found that, in one example, switching enrollees to these plans cut overall spending by one third. And while patients had access to fewer hospitals, the hospitals that were in network were of equally good quality.

Then there’s the Medicare side of the equation, where there has been a unprecedented decline in per person spending. Margot Sanger-Katz at the Upshot has had two fantastic posts on Medicare’s cost slowdown. One of them points out the fact that, since 2010, per patient spending has grown slower than the rest of the economy. You can see that in this graph, which charts “excess cost growth” in Medicare (health wonk speak for cost growth above and beyond inflation). For the past few years, excess growth has been replaced by slower-than-the-economy growth.

As Sanger-Katz points out, there are two trends at play in Medicare. One is that younger baby boomers keep aging onto the program. They’re younger than Medicare’s really old patients, and typically less expensive to care for. That drives down per person spending for the whole population.

But there’s something else going on that looks to be a more permanent trend: Medicare patients are using less expensive care. They go to the doctor more, and the hospital less. You can see this in new data from the Medicare Trustees’ report, which shows per person spending on Medicare Part A (the program that covers inpatient care) falling over the past few years.

/cdn2.vox-cdn.com/assets/4826288/medicare_per_person.png)

Because of this shift away from hospital care, Medicare Part A now spends less money to cover more people. It paid $266.8 billion covering 50.3 million people in 2012. In 2013, the the same program spent $266.2 billion to cover 51.9 million people.

We have had periods of relatively slow health care growth before. In the mid-1990s, for example, there was a stretch of time when health spending grew at the same rate as the rest of the economy. You can see that in this graph.

/cdn2.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/679852/helath_growth.0.png)

Most health economists attribute that to the rise of health maintenance organizations, or HMOs, that sharply limited access to specialists. Patients, unsurprisingly, didn’t like those limitations and there was a backlash. HMOs declined and health spending rose again.

But some health economists say that this time feels different. For one, the changes are happening in private insurance and Medicare, suggesting there’s no single — and thus easily reversible — force driving the change.

And while there are more patients in narrow network products, something akin to HMOs, consumers are often choosing to be there. These are shoppers on the Obamacare exchanges who have decided to make a trade off: they’re take lower premiums for less choice of doctor.

“In the 1990s, people were essentially stuck in HMOs,” M.I.T economist Gruber says. “This time, people are given an option and make a choice. That’s why I’m more confident this slower growth will stick.”

Medicare actuaries are not fortune tellers; they do not have a crystal ball that conjures up the future of health care with perfect clarity. But at least at this particular moment, there are lots of signs cropping up to suggest something very important in health care is changing, and it’s for the better.

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-09-11/how-big-data-peers-inside-your-medicine-chest.html

The 42-year-old information technology worker’s name recently showed up in a database of millions of people with “diabetes interest” sold by Acxiom Corp. (ACXM), one of the world’s biggest data brokers. One buyer, data reseller Exact Data, posted Abate’s name and address online, along with 100 others, under the header Sample Diabetes Mailing List. It’s just one of hundreds of medical databases up for sale to marketers.

In a year when former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden’s revelations about the collection of U.S. phone data have sparked privacy fears, data miners have been quietly using their tools to peek into America’s medicine cabinets. Tapping social media, health-related phone apps and medical websites, data aggregators are scooping up bits and pieces of tens of millions of Americans’ medical histories. Even a purchase at the pharmacy can land a shopper on a health list.

“People would be shocked if they knew they were on some of these lists,” said Pam Dixon, president of the non-profit advocacy group World Privacy Forum, who has testified before Congress on the data broker industry. “Yet millions are.”

They’re showing up in directories with names like “Suffering Seniors” or “Aching and Ailing,” according to a Bloomberg review of this little-known corner of the data mining industry. Other lists are categorized by diagnosis, including groupings of 2.3 million cancer patients, 14 million depression sufferers and 600,000 homes where a child or other member of the household has autism or attention deficit disorder.

The lists typically sell for about 15 cents per name and can be broken down into sub-categories, like ethnicity, income level and geography for a few pennies more.

Some consumers may benefit, like those who find out about a new drug or service that could improve their health. And Americans are already used to being sliced and diced along demographic lines. Lawn-care ads for new homeowners and diaper coupons for expecting moms are as predictable as the arrival of the AARP magazine on the doorsteps of the just-turned 50 set. Yet collecting massive quantities of intimate health data is new territory and many privacy experts say it has gone too far.

“It is outrageous and unfair to consumers that companies profiting off the collection and sale of individuals’ health information operate behind a veil of secrecy,” said U.S. Senator Jay Rockefeller, a West Virginia Democrat. “Consumers deserve to know who is profiting.”

Rockefeller and U.S. Senator Edward Markey, a Democrat from Massachusetts, introducedlegislation in February that would allow consumers to see what information has been collected on them and make it easier to opt out of being included on such lists. In May, the Federal Trade Commission recommended Congress put more protections around the collection of health and other sensitive information to ensure consumers know how the details they are sharing are going to be used.

The companies selling the data say it’s secure and contains only information from consumers who want it shared with marketers so they can learn more about their condition. The data broker trade group, the Direct Marketing Association, said it has its own set of mandatory guidelines to ensure the data is ethically collected and used. It also has a website to allow consumers to opt out of receiving marketing material.

“We have very strong self regulation, we have for more than 40 years,” said Rachel Nyswander Thomas, vice president for government affairs for the DMA. “Regardless of how the practices are evolving, the self-regulation is as strong as ever.”

Yet the ease with which data is discoverable in a simple Google search along with Bloomberg interviews with people who showed up in one such database suggest the process isn’t always secure or transparent.

Dan Abate said he never agreed to be included in any list related to diabetes. Two other people on the same mailing list said they didn’t have diabetes either and weren’t aware of consenting to offer their information.

In Abate’s case, neither he nor anyone in his family or household has diabetes and the only connection he can think of for landing on the list are a few cycling events he participated in for a group that raises money for the disease.

“I could understand if I was voluntarily putting this medical information out there,” Abate said. “But I don’t have diabetes, and I don’t want my information out there to be sold.”

Bloomberg found the diabetes mailing list on the website of Exact Data in a section for sample lists that included dozens of other categories, like gamblers and pregnant women. The diabetes list contained 100 names, addresses and e-mails. Bloomberg sent e-mails to all of them, and three consented to interviews. There were no restrictions on who could access the list, available on search engines like Google.

Exact Data’s Chief Executive Officer Larry Organ said the list posted on its website shouldn’t have included last names and street addresses, and the company has since deleted any identifiable information. He said the data came from Acxiom and Exact Data was reselling it.

The Acxiom list was compiled by various sources, including surveys, registrations, or summaries of retail purchases that indicated someone in the household has an interest in diabetes, said Ines Gutzmer, a spokeswoman for the Little Rock, Arkansas-based company. While Gutzmer said consumers can visit the Acxiom website to see some of the information that has been collected on them, she declined to comment about how any one individual was placed on the list.

Acxiom shares rose less than 1 percent, to $18.66 at the close of New York trading. The company has lost 29 percent of its value in the past 12 months.

One of the more common ways to end up on a health list is by sharing health information on a mail or online survey, according to interviews with data brokers and the review of dozens of health-related lists. In some cases the surveys are tied to discounts or sweepstakes. Others are sent by a company seeking customer feedback after a purchase. The information is then sold to data brokers who repackage and resell it.

Epsilon, which has data on 54 million households based on information gathered from its Shopper’s Voice survey, has lists containing information on 447,000 households in which someone has Alzheimer’s, 146,000 with Parkinson’s disease, and 41,000 with Lou Gehrig’s disease. The Irving, Texas-based company provides survey respondents with coupons and a chance to win $10,000 in exchange for information on their household’s spending habits and health.

The company will share with individual consumers specific information it has gathered, said Jeanette Fitzgerald, Epsilon’s chief privacy officer.

KBM Group, one of the largest collectors of consumer health data based in Richardson, Texas, has health information on at least 82 million consumers categorized by more than 100 medical conditions obtained from surveys conducted by third-party contractors. The company declined to provide an example of the surveys. KBM uses the information for its own marketing clients, and sells it to other data brokers, said Gary Laben, chief executive officer of KBM.

“None of our clients wants to engage with consumers or businesses who don’t want to engage with them,” he said. “Our business is about creating mutual value and if there is none, the process doesn’t work.”

Data repackaging is extensive and pervasive. The Suffering Seniors Mailing List help marketers push everything from lawn care to financial products. It consists of the names, addresses, and health information of 4.7 million “suffering seniors,” according to promotional material for the list. Beach List Direct Inc. sells the information for 15 cents a name. Marketed as “the perfect list for mailers targeting the ailing elderly,” it contains a breakdown of those with diseases like depression, cancer and Alzheimer’s, according to its seller’s website.

Clay Beach, the contact on Beach List’s website, did not return calls and e-mails over the past month.

Little is known about who buys medical lists since data brokers say their clients are confidential, Rockefeller said at a hearing on the issue in December.

Promotional material for the Suffering Seniors data found by Bloomberg on Beach List’s website initially included a list of users. The names of those users have since been removed.

One customer was magazine publisher Meredith Corp. (MDP), which used the list in a test for a subscription offer for Diabetic Living magazine, said Jenny McCoy, a spokeswoman. Other users have included the American Diabetes Association, which said a small portion of names from the list was given to one of its local chapters, and Remedy Health Media, a publisher of medical websites.

Remedy Health may have used the list to advertise one of its magazines, which has been defunct for several years, said David Lee, the company’s executive vice president of publishing.

A growing source of data fodder are website registration forms that ask for health information in order for a user to access the site or receive an e-mail newsletter.

One such site is Primehealthsolutions.com, which provides basic health information on a variety of conditions. It makes money by collecting data on diseases its users have been diagnosed with and medications they are taking, which people disclose when signing up for the site’s e-mail newsletter.

The site has more than three dozen lists for sale, including a tally of 2.2 million people with depression, 267,000 with Alzheimer’s, 553,000 with impotence, and 2.1 million women going through menopause.

Jason Rines, a co-owner of Prime Health Solutions, said he will share the lists only with those marketing health-related products, like pharmaceutical or medical device makers.

Acxiom said it uses retail purchase history or magazine subscriptions to make assessments about whether someone has a particular disease interest.

Health data collection is troubling to people like Rebecca Price, who has early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. While she now makes no secret of her disease and serves as a member of the Alzheimer’s Association’s early stage advisory group, that wasn’t always the case. Price, a 62-year-old former doctor, said she initially didn’t even tell her husband of her condition for fear word would get out and harm her personally and financially.

“It is a very, very personal diagnosis,” Price said.

Social media is another potential way information can be collected on patients, said Dixon, of the World Privacy Forum, who warns patients to be more careful about what they share on sites like Facebook.

“Don’t ‘like’ the hospital website or comment ‘thank you for the great breast cancer screening you gave me,’” she said. “Under the Facebook policy that is public information and it is in the wild and if someone goes to that site and pulls it off, it is totally public.”

While it would be possible for data miners to scrape ‘likes’ and public comments from Facebook Inc. (FB)’s social network, the company said such practice is against company policy and, if discovered, would be blocked.

“We don’t allow third-party data providers to scrape or collect information without our permission,” said Facebook spokeswoman Elisabeth Diana. “Third-party data providers that work with Facebook don’t collect personally identifiable information and are subject to our policies.”

For consumers who want to know what list they may be on, there are limited options. KBM for example doesn’t have the technological capabilities to look up an individual by name and tell them what lists they are on, though they can purge a name from all their lists if requested to do so, said CEO Laben.

Acxiom started a website last year that allows people to view some of the information it has on them. Those who choose to can correct or remove their data.

Epsilon’s Fitzgerald says the best way for consumers to protect themselves is to be more aware of where they are sharing their information and pay more attention to website privacy policies.

“If people are concerned, don’t put the information out there,” Fitzgerald said. “Consumers would be better served if they were educated more on what is going on on the web.”

(A previous version of the story mistated the name of the Direct Marketing Association and corrected the spelling of Facebook spokeswoman Elisabeth Diana.)

To contact the reporters on this story: Shannon Pettypiece in New York atspettypiece@bloomberg.net; Jordan Robertson in San Francisco atjrobertson40@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Rick Schine at eschine@bloomberg.net Drew Armstrong

Another cracking, clean head shot from Terry… totally concur with this one!

http://www.afr.com/p/business/healthcare2-0/doctors_have_fat_co_payment_scheme_g9tVCa7kjp7RkGhXIHh3tN

PUBLISHED: 13 AUG 2014 00:05:00 | UPDATED: 20 AUG 2014 11:53:54

Even if Medicare rebates don’t cover the full cost of medical services plus a reasonable margin, their subsidies make costly specialist services accessible and affordable to most Australians on low to middle incomes. Photo: Glenn Hunt

TERRY BARNES

While relentlessly attacking the federal budget’s $7 co-payment on bulk-billed GP services measure as unfair, neurosurgeon and Australian Medical Association president Brian Owler asserts doctors’ rights to charge co-payments generally. His specialist members certainly do with gusto, and presumably he does too.

If he but realises it, Health Minister Peter Dutton is ideally placed to drive a hard bargain with the AMA on containing excessive out-of-pockets, especially given the doctors’ trade union is pressuring the government to dump the $5 cut to Medicare rebates intended to drive GPs to charge the co-payment.

The ace up Dutton’s sleeve is that doctors, particularly surgeons and specialists, depend on Medicare income like a smoker depends on his nicotine fix. Even if Medicare rebates don’t cover the full cost of medical services plus a reasonable margin, their subsidies make costly specialist services accessible and affordable to most Australians on low to middle incomes, especially the pensioners and fixed-income retirees who dominate the demand for medical services.

Given this financial reality, the government should use its domination of purchasing by Medicare on behalf of patients to bring the AMA to heel on excessive specialist charging. Doctors are entitled to a fair and reasonable fee above the Medicare schedule fee, and there’s no cap on what doctors can charge, but too many specialists have assumed this is carte blanche to gouge poor paying punters.

To end specialist billing rorts, the government can and should impose out-of-pocket capping that is simple, elegant, and transparent, using the AMA’s own benchmarks against it.

The AMA has its own private fee schedule, in which it determines what it considers appropriate prices for specific Medicare service items. AMA fees have long been an unofficial benchmark for doctors, the association stressing that it is staying on the right side of competition law by offering general advice to its members rather than giving them direction. The government’s published Medicare schedule fee observance and out-of-pocket data indicate that a great many doctors, notably GPs, apply the AMA recommended fee when they don’t bulk bill.

What’s more, specialist association submissions to the current Senate inquiry into patient out-of-pocket expenses repeatedly cite AMA recommended fees as being fair and reasonable, especially when compared with what they depict as woefully inadequate Medicare rebates.

With this in mind, the government should take doctors at their word and insist, as a condition of specialists’ access to Medicare, that patient contributions for any billed service that exceed AMA recommended fees will be prohibited. If doctors exceeds this cap, they could be fined have their Medicare billing rights suspended or cancelled, and be required to refund gouged patients their contributions plus credit care-level interest. The current but secret AMA recommended fee schedule would be published as a baseline, and subsequently indexed annually under a formula agreed by the government and the profession.

Recommended fees for future new items would be set by the AMA and relevant specialist colleges in consultation with the government.

Should a doctor want to be more competitive on price, there would be no prohibition on their charging a fee lower than the AMA’s recommendation.

But they would not be permitted to exceed it if they bill Medicare as their patients would expect.

Further, private health insurers should be permitted to cover the gap between specialist Medicare rebates and AMA recommended fees. This would be fairer to patients than current arrangements in which insurers have no gap, or no known gap deals with some specialists but not with others. It would also tackle those GPs and specialists, most notoriously anaesthetists, who blatantly ignore their patients’ rights to be informed of and consent to fees before a service is provided.

Private insurers also should be able to advise their members on the comparative performance of doctors, especially in relation to price. In a market for health services bedevilled by information asymmetry, insurers have a wealth of consumer knowledge that can be shared without compromising the privity of the doctor-patient relationship. Let them share it. For too long, medical specialists have got away with ripping off patients through excessive charging practices. Dutton, therefore, should use his negotiations with the AMA to take a stand for patients, call Owler’s bluff, and wield his own market power to bring the AMA to heel over specialists’ stubborn, arrogant and contemptuous disregard for their patients as customers. If the minister does take on the AMA over blatant fee-gouging, he’d be onto a political winner.

Terry Barnes authored the Australian Centre for Health Research’s $7 GP co-payment proposal.

The Australian Financial Review

http://www.theguardian.com/society/the-shape-we-are-in-blog/2014/aug/13/diabetes-usdomesticpolicy

How much worse can the type 2 diabetes epidemic get? Shockingly, a new study published by a leading medical journal says that 40% of the adult population of the USA is expected to be diagnosed with the disease at some point in their lifetime. And among Hispanic men and women and non-Hispanic black women, the chances are even higher – one in two appear to be destined to get type 2 diabetes.

As Public Health England spelled out in a recent report urging local authorities to take action, 90% of people with type 2 diabetes are overweight or obese. There is no mystery behind the rise in diagnoses – they match the soaring weight of the population. The climb dates back to the 1980s and is associated with our more sedentary lifestyles and changing eating habits – more food, containing more calories, more often. It is those things that will have to be tackled if the epidemic is to be contained.

The new study in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology journal, from a team of researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, shows that the risk of developing type 2 diabetes for the average 20 year-old American rose from 20% for men and 27% for women in 1985–1989, to 40% for men and 39% for women in 2000–2011. The study was big – involving data including interviews and death certificates from 600,000 Americans.

Americans are generally living longer, which is a factor in their increased lifetime chance of developing type 2 diabetes. They are also not dying in the same proportions that they were, because of better treatment. However, that means they are going to spend far more years of their lives suffering from type 2 diabetes, which can lead to blindness and foot amputations as well as heart problems.

This is very bad news for the US healthcare system, says Dr Edward Gregg, study leader and chief of the epidemiology and statistics branch of the Division of Diabetes Translation at CDC:

As the number of diabetes cases continue to increase and patients live longer there will be a growing demand for health services and extensive costs. More effective lifestyle interventions are urgently needed to reduce the number of new cases in the USA and other developed nations.

Both he and Canada-based Dr Lorraine Lipscombe, who has written a commentary on the study, point out that the situation in the US is unlikely to be much different from that elsewhere in the developed world. Dr Lipscombe, from Women’s College Hospital and the University of Toronto, writes:

The trends reported by Gregg and colleagues are probably similar across the developed world, where large increases in diabetes prevalence in the past two decades have been reported.

Primary prevention strategies are urgently needed. Excellent evidence has shown that diabetes can be prevented with lifestyle changes. However, provision of these interventions on an individual basis might not be sustainable.

Only a population-based approach to prevention can address a problem of this magnitude. Prevention strategies should include optimisation of urban planning, food-marketing policies, and work and school environments that enable individuals to make healthier lifestyle choices. With an increased focus on interventions aimed at children and their families, there might still be time to change the fate of our future generations by lowering their risk of type 2 diabetes.

President Dwight Eisenhower’s Farewell Address to the nation January 17, 1961

In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.

We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes. We should take nothing for granted only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of huge industrial and military machinery of defense with our peaceful methods and goals, so that security and liberty may prosper together.

….

The prospect of domination of the nation’s scholars by Federal employment, project allocations, and the power of money is ever present and is gravely to be regarded.

Yet, in holding scientific research and discovery in respect, as we should, we must also be alert to the equal and opposite danger that public policy could itself become the captive of a scientific-technological elite.

It is the task of statesmanship to mold, to balance, and to integrate these and other forces, new and old, within the principles of our democratic system-ever aiming toward the supreme goals of our free society.

My fellow Americans:

Three days from now, after half a century in the service of our country, I shall lay down the responsibilities of office as, in traditional and solemn ceremony, the authority of the Presidency is vested in my successor.

This evening I come to you with a message of leave-taking and farewell, and to share a few final thoughts with you, my countrymen.

Like every other citizen, I wish the new President, and all who will labor with him, Godspeed. I pray that the coming years will be blessed with peace and prosperity for all.

Our people expect their President and the Congress to find essential agreement on issues of great moment, the wise resolution of which will better shape the future of the Nation.

My own relations with the Congress, which began on a remote and tenuous basis when, long ago, a member of the Senate appointed me to West Point, have since ranged to the intimate during the war and immediate post-war period, and, finally, to the mutually interdependent during these past eight years.

In this final relationship, the Congress and the Administration have, on most vital issues, cooperated well, to serve the national good rather than mere partisanship, and so have assured that the business of the Nation should go forward. So, my official relationship with the Congress ends in a feeling, on my part, of gratitude that we have been able to do so much together.

II

We now stand ten years past the midpoint of a century that has witnessed four major wars among great nations. Three of these involved our own country. Despite these holocausts America is today the strongest, the most influential and most productive nation in the world. Understandably proud of this pre-eminence, we yet realize that America’s leadership and prestige depend, not merely upon our unmatched material progress, riches and military strength, but on how we use our power in the interests of world peace and human betterment.

III

Throughout America’s adventure in free government, our basic purposes have been to keep the peace; to foster progress in human achievement, and to enhance liberty, dignity and integrity among people and among nations. To strive for less would be unworthy of a free and religious people. Any failure traceable to arrogance, or our lack of comprehension or readiness to sacrifice would inflict upon us grievous hurt both at home and abroad.

Progress toward these noble goals is persistently threatened by the conflict now engulfing the world. It commands our whole attention, absorbs our very beings. We face a hostile ideology-global in scope, atheistic in character, ruthless in purpose, and insidious in method. Unhappily the danger it poses promises to be of indefinite duration. To meet it successfully, there is called for, not so much the emotional and transitory sacrifices of crisis, but rather those which enable us to carry forward steadily, surely, and without complaint the burdens of a prolonged and complex struggle-with liberty at stake. Only thus shall we remain, despite every provocation, on our charted course toward permanent peace and human betterment.

Crises there will continue to be. In meeting them, whether foreign or domestic, great or small,there is a recurring temptation to feel that some spectacular and costly action could become the miraculous solution to all current difficulties. A huge increase in newer elements of our defense; development of unrealistic programs to cure every ill in agriculture; a dramatic expansion in basic and applied research-these and many other possibilities, each possibly promising in itself, may be suggested as the only way to the road we which to travel.

But each proposal must be weighed in the light of a broader consideration: the need to maintain balance in and among national programs-balance between the private and the public economy, balance between cost and hoped for advantage-balance between the clearly necessary and the comfortably desirable; balance between our essential requirements as a nation and the duties imposed by the nation upon the individual; balance between action of the moment and the national welfare of the future. Good judgment seeks balance and progress; lack of it eventually finds imbalance and frustration.

The record of many decades stands as proof that our people and their government have, in the main, understood these truths and have responded to them well, in the face of stress and threat. But threats, new in kind or degree, constantly arise. I mention two only.

IV

A vital element in keeping the peace is our military establishment. Our arms must be mighty, ready for instant action, so that no potential aggressor may be tempted to risk his own destruction.

Our military organization today bears little relation to that known by any of my predecessors in peace time, or indeed by the fighting men of World War II or Korea.

Until the latest of our world conflicts, the United States had no armaments industry. American makers of plowshares could, with time and as required, make swords as well. But now we can no longer risk emergency improvisation of national defense; we have been compelled to create a permanent armaments industry of vast proportions. Added to this, three and a half million men and women are directly engaged in the defense establishment. We annually spend on military security more than the net income of all United State corporations.

This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. The total influence-economic, political, even spiritual-is felt in every city, every state house, every office of the Federal government. We recognize the imperative need for this development. Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. Our toil, resources and livelihood are all involved; so is the very structure of our society.

In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.

We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes. We should take nothing for granted only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of huge industrial and military machinery of defense with our peaceful methods and goals, so that security and liberty may prosper together.

Akin to, and largely responsible for the sweeping changes in our industrial-military posture, has been the technological revolution during recent decades.

In this revolution, research has become central; it also becomes more formalized, complex, and costly. A steadily increasing share is conducted for, by, or at the direction of, the Federal government.

Today, the solitary inventor, tinkering in his shop, has been over shadowed by task forces of scientists in laboratories and testing fields. In the same fashion, the free university, historically the fountainhead of free ideas and scientific discovery, has experienced a revolution in the conduct of research. Partly because of the huge costs involved, a government contract becomes virtually a substitute for intellectual curiosity. For every old blackboard there are now hundreds of new electronic computers.

The prospect of domination of the nation’s scholars by Federal employment, project allocations, and the power of money is ever present and is gravely to be regarded.

Yet, in holding scientific research and discovery in respect, as we should, we must also be alert to the equal and opposite danger that public policy could itself become the captive of a scientific-technological elite.

It is the task of statesmanship to mold, to balance, and to integrate these and other forces, new and old, within the principles of our democratic system-ever aiming toward the supreme goals of our free society.

V

Another factor in maintaining balance involves the element of time. As we peer into society’s future, we-you and I, and our government-must avoid the impulse to live only for today, plundering, for our own ease and convenience, the precious resources of tomorrow. We cannot mortgage the material assets of our grandchildren without risking the loss also of their political and spiritual heritage. We want democracy to survive for all generations to come, not to become the insolvent phantom of tomorrow.

VI

Down the long lane of the history yet to be written America knows that this world of ours, ever growing smaller, must avoid becoming a community of dreadful fear and hate, and be, instead, a proud confederation of mutual trust and respect.

Such a confederation must be one of equals. The weakest must come to the conference table with the same confidence as do we, protected as we are by our moral, economic, and military strength. That table, though scarred by many past frustrations, cannot be abandoned for the certain agony of the battlefield.

Disarmament, with mutual honor and confidence, is a continuing imperative. Together we must learn how to compose difference, not with arms, but with intellect and decent purpose. Because this need is so sharp and apparent I confess that I lay down my official responsibilities in this field with a definite sense of disappointment. As one who has witnessed the horror and the lingering sadness of war-as one who knows that another war could utterly destroy this civilization which has been so slowly and painfully built over thousands of years-I wish I could say tonight that a lasting peace is in sight.

Happily, I can say that war has been avoided. Steady progress toward our ultimate goal has been made. But, so much remains to be done. As a private citizen, I shall never cease to do what little I can to help the world advance along that road.

VII

So-in this my last good night to you as your President-I thank you for the many opportunities you have given me for public service in war and peace. I trust that in that service you find somethings worthy; as for the rest of it, I know you will find ways to improve performance in the future.

You and I-my fellow citizens-need to be strong in our faith that all nations, under God, will reach the goal of peace with justice. May we be ever unswerving in devotion to principle, confident but humble with power, diligent in pursuit of the Nation’s great goals.

To all the peoples of the world, I once more give expression to America’s prayerful and continuing inspiration:

We pray that peoples of all faiths, all races, all nations, may have their great human needs satisfied; that those now denied opportunity shall come to enjoy it to the full; that all who yearn for freedom may experience its spiritual blessings; that those who have freedom will understand, also, its heavy responsibilities; that all who are insensitive to the needs of others will learn charity; that the scourges of poverty, disease and ignorance will be made to disappear from the earth, and that, in the goodness of time, all peoples will come to live together in a peace guaranteed by the binding force of mutual respect and love.

Transcription courtesy of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum.

Interesting take on imagining the future of healthcare.

http://www.kevinmd.com/blog/2014/08/uber-health-care-will-look-like.html

Medallion owners tend to fall into two categories: private practitioners and fleet owners. Private practitioners own their own car, have responsibility for maintenance, gas and insurance, and tend to use the cash flow to live while allowing the medallion to appreciate over the course of their career. They then cash out as part of their retirement plan.

Fleet owners have dozens of medallions; they lease or buy fleets of automobiles and often have their own mechanics, car washes and gas pumps. They either hire drivers as employees or, more often, rent their cars to licensed taxi drivers who get to keep the balance of their earnings after their car and gas payments.

In London, taxi drivers have to invest 2 to 4 years of apprenticeship before they can take and pass a test called “The Knowledge.” However, like NYC, finally getting that a licence to operate a Black Cab in London is a hard-working but stable way to earn a living.

Now imagine that someone comes along that can offer all the services of the NYC yellow cab or the London Black Cab directly to the general public, but does not have to own the medallion, own the car or employ the driver. With as much as 70% lower overhead, they provide the same service to the consumer; in fact they are so consumer friendly that they become the virtual gatekeeper for all the taxi and car service business in the community.

How, you ask? Outsourcing the overhead and just-in-time inventory management; they convince thousands of people to drive around in their own cars with the promise of a potential payment for services driving someone from point A to point B. All these drivers have to do is meet certain standards of quality and safety. This new company does all the marketing and uses technology to make the connection between the currently active drivers and those in need of a ride; they provide simple and transparent access to a host of cars circulating in your neighborhood, let you know the price and send a picture and customer rating of the driver, all before he or she arrives, and they process the payment so no money ever changes hands.

This is the premise behind Uber, a very disruptive take on the taxi business. As a recent article in Bloomberg noted, the slower rate of growth in medallion value is already attribute to the very young company; a recent protest by Black Cab drivers in London resulting in an eight-fold increase in Uber registrations.

Now imagine that a new health care services company comes to your community offering population health management services on a bundled payment or risk basis. They guarantee otherwise inaccessible metrics of quality and safety to both large employers and individual consumers. They employ only a handful of doctors, but do not own any hospitals, imaging centers or ambulatory care facilities.

However, they are masters at consumer engagement, creating levels of affinity and loyalty usually found with consumer products and soft drinks. They use a don’t make me think approach to their technology, seamlessly integrating analytics and communications platforms into their customers lives, and offer consumers without a digital footprint a host of options for communications, including access to information and services via their land lines or their cable TV box. They leverage high-level marketing analytics to determine who will be responsive to non-personal tools for engagement, like digital coaching, and who requires a human touch.

Care planning is done based on clinical stratification and evidence; population specific data is used to determine the actual resources required to achieve clinical, quality and financial goals. (A Midwest ACO has more problems with underweight than obesity, do they need to maintain their bariatric surgery center?) Physicians serve as “clinical intelligence officers,” creating standing orders across the entire population, implemented by non-clinical personnel; they also create criteria for escalation and de-escalation of services and resource allocation based on individual patients progress towards goals. They employ former actors and actresses as health coaches and navigators, invest heavily in home care and nurse care managers and use dieticians in local supermarkets to support lifestyle changes (while accessing and analyzing the patients point-of-purchase data to see what they are really buying).

The primary relationship between patients and their health systems is with a low cost, personal health concierge: Primary care physicians are only accessed based on predetermined eligibility criteria and only with those physician who agree to standards of quality and accountability are in the network. Multi-tiered scenario planning for emergencies is built into the system. For professional resources only required on an as-needed basis, such as hospital beds, surgeons and medical specialists, access is negotiated in advance based on a formula of quality standards and best pricing but only used on a just-in-time basis.

They are not a payer, although a professional relationship with them is on a business-to-business basis. They are a completely new type of health system, guaranteeing health and well being, transparent in their operations and choosing their vendors based on their willingness and ability to achieve those goals. In doing so, they significantly reduce the resources necessary to achieve goals for quality of care and quality of health across the entire population; they treat quality achievement as an operational challenge and manage their supply chain accordingly.

Am I suggesting this a new model of care? No, I am personally an advocate for physician-driven systems of care. But this kind of system is very possible, and there are companies working on models of national ACOs using many of these principles.

The Uber of health care will have much less to do with the mobile app; and far more to do with creating value by minimizing overhead, designing flexible operations, supporting goal-directed innovation and bringing supply-chain discipline to the idea of resource-managed care delivery. It will involve embracing models of care delivery that leverage emerging evidence on non-clinical approaches to health status and quality improvement, and focusing on designing goal-directed interactions between people, platforms, programs and partners.

I can hear more than a few of you creating very good reasons why it wont work (“You can’t put an ICU bed out to bid!”), but these scenarios are very doable. If we want to revitalize the experience of care for patients and professionals, we must be willing to acknowledge and embrace dramatically different, often counter-intuitive, new operating models for care that will require new competencies, forms of collaboration and reengineering the roles and responsibilities of those who comprise a patients’ health resource community.

Steven Merahn is director, Center for Population Health Management, Clinovations. He blogs at MedCanto.

Good call…

http://www.medicalobserver.com.au/news/call-to-cap-specialists-fees-gathers-support

Flynn Murphy all articles by this author

THE former Howard government adviser who reignited the co-payment debate is back. In his sights: exorbitant out-of-pocket expenses being charged by overpaid specialists.

Terry Barnes has called for the fees that surgeons and other specialists can charge to be capped at their AMA-recommended rates. And if they charge too much they should be refused access to Medicare, he told Medical Observer.

“If the AMA schedule is considered fair and reasonable, then any out-of-pocket in excess of that is, by definition, unreasonable,” Mr Barnes said.

“What I propose is that if the government gives ground on cutting the GP rebate [for the co-payment], the quid pro quo is that the government works together with the AMA to reduce patient out-of-pockets.”

Mr Barnes showed MO a recent anaesthetist’s bill that saw him pay four times the rebate he was entitled to under the MBS.

“She should have delivered an anaesthetic with her [bill],” he said.

The proposal is backed by the Grattan Institute’s Dr Stephen Duckett, a prominent health economist who gave evidence to the recent Senate inquiry into out-of-pocket costs.

In his submission to the inquiry, Dr Duckett reported that for people in the lowest disposable income decile, average fees for specialists were nearly four times the average GP fee.

“I think it’s a good idea,” he said of Mr Barnes’s call.

“I think the profession has to have some responsibility for moderating out-of-pocket costs. There is an issue here about professional responsibility.”

The comments follow a statement from the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (RACS) expressing concern about reports of “excessive… even extortionate” and “unethical” surgical fees being charged to patients by its own members.

RACS president Professor Michael Grigg said the reported fees were “damaging to the health system and to the standing of surgeons and the surgical profession”.

“RACS believes that extortionate fees, where they are manifestly excessive and bear little if any relationship to utilisation of skills, time or resources, are exploitative and unethical. As such, they are in breach of the college’s code of conduct and will be dealt with by the college,” the statement said.

But an RACS spokesman said the college does not support a cap on fees.

An AMA spokesman said: “The AMA is currently in talks with the government on the disastrous and hugely unpopular budget co-payments proposal, and doubts that the government would be rushing to adopt any other ‘thought bubbles’ from the author of that policy.”

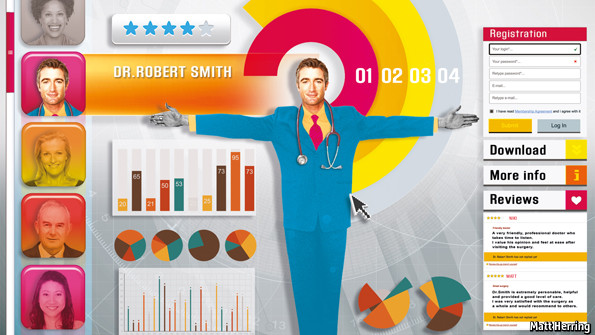

http://www.economist.com/news/international/21608767-patients-around-world-are-starting-give-doctors-piece-their-mind-result?fsrc=scn/tw_ec/docadvisor

WHEN a patient in Illinois did not like the result of her breast-augmentation surgery, she reacted like many dissatisfied customers: by writing negative comments about her doctor on websites that feature such reviews. Her breasts, she said, looked like something out of a horror movie. Other unhappy patients joined her online, calling the doctor “dangerous”, “horrible” and a “jackass”. He sued them for defamation. (The cases were later dropped.)

Other doctors have filed similar lawsuits, mostly in America. Though few have won, their reaction illustrates a discomfort with patient reviews felt by many of their colleagues. Some question the accuracy and relevance of the feedback; others complain that privacy rules prevent them from responding. Sites often have just a handful of ratings per doctor, meaning results can be skewed by a single bad write-up.

But increasingly, doctors cannot afford to ignore them. They often lead the results of searches for doctors’ names. In America, the world’s biggest health-care market, firms that offer health insurance are making employees pay a bigger share, pushing them to search for guidance online. The most sophisticated sites are attracting more users by including reviews and other features. ZocDoc also lets patients make appointments. Offerings from Vitals include a quality indicator it has built using data from 170,000-odd sources. Castlight Health includes prices gathered from insurance bills and other data. The differences can be startling—the cost of a brain scan in Philadelphia ranges from $264 to $3,271.

With around 60 review sites, America leads the way. But they are also popping up in other countries where patients pay for at least part of their care. Practo, an Indian firm that schedules appointments with doctors, plans to start publishing patients’ reviews later this year. More and more Chinese patients, who generally do not have a regular family doctor, are using a site run by Hao Dai Fu (“good doctor”) to navigate their country’s unstructured health system, says Haijing Hao of the University of Massachusetts. It has profiles of around 300,000 doctors and over 1m reviews.

Increasingly, doctors, hospitals and health systems are seeking to turn the trend to their advantage. Some now offer incentives, such as prize draws, for patients to go online and rate them. A survey by ZocDoc found that 85% of doctors on its site looked at their ratings last year. And a handful of health-care providers have even started to publish reviews themselves. The University of Utah, which runs four hospitals and ten clinics, was one of the first, in 2012. Its doctors’ complaints about independent sites encouraged it to publish patient feedback that was already being collected for internal use. Some of its doctors now have hundreds of reviews.

Preparing staff for the publication of all the comments, good and bad, took a year, says Brian Gresh, who helped create the university’s system. But their worries appear to have been groundless: most reviews are positive, and patient-satisfaction scores improved after the move. Happy patients communicate and co-operate better with their doctors, says Tom Lee, the chief medical officer of Press Ganey, a firm that surveys patients on behalf of health-care providers, including for the University of Utah. Its boss, Pat Ryan, predicts that plenty of other hospitals will follow suit.

Some doctors are still sceptical, fearing, for example, that patients may judge a hospital on its decor rather than its care. But patients are rarely swayed much by such trivia, insists Mr Ryan: “If you have flat-screen televisions and your communication is poor, you will get very bad scores.” Moreover, the feedback reminds doctors that every meeting with a patient matters, so they try harder.

America’s government has started to link health-care payments with patient feedback: Medicare, a federal scheme for over-65s, recently started to give bonuses to hospitals that score well. The Cleveland Clinic, a big hospital, uses these data to improve its care. Britain’s National Health Service has surveyed patients for over a decade (though not on the performance of individual doctors) and published the results online—though some think it could use its findings better.

But many other governments do not even ask patients for their opinions. German doctors and hospitals, for example, have fought efforts to link funding with quality of care, says Maria Nadj-Kittler of the Picker Institute Europe, a research organisation, and are therefore hostile to patient reviews. This is a missed opportunity. Patients who hold their doctors accountable make them better and more efficient. That is good news no matter who pays.