Earlier this week I spoke at a symposium on nutrition and public health at the Tuck School of Business at my alma mater in beautiful Hanover, N.H., Dartmouth College. Among others on the panel with me was Richard Starmann, the former head of Corporate Communications for McDonald’s. Those with even a modest number of Katz-column frequent flyer miles can readily guess how often he and I agreed.

One point Mr. Starmann made, more than once, was that rampant obesity and related chronic disease was enormously, intractably complicated and would require diverse efforts, a great deal of private sector innovation, minimal government intercession, lots of time, lots of money, and many conferences, committees and panels such as the one we were on to fix. I had trouble deciding where to start disagreeing with this one.

For one thing, if you have ever served on a committee, you likely know as well as I that the surest way to never fix something is to convene a whole lot of committees and panels to explore every possible way of disagreeing. Just look at our Congress.

But more importantly: Obesity is not complicated. And neither is fixing it. Hard, yes; complicated, no!

Before I make that case — emphatically — a brief pause to note the essentials of informed compassion. Yes, it is absolutely true that some people eat well and exercise, and are heavy anyway. Yes, it is absolutely true that two people can eat and exercise the same, and one gets fat and the other stays thin due to variations in genetics and metabolism. Yes, it is absolutely true that some people gain weight very easily, and find it shockingly hard to lose. Yes, it is absolutely true that the quality of calories matters, along with the quantity. Yes, it is absolutely true that factors other than calories in/calories out may influence weight and certainly health, including such candidates as the microflora of our intestinal tracts, exposure to hormones, GMOs, and more.

But on the other hand, once we contend effectively with the fact that we eat way too many calories, that “junk” is perceived as a legitimate food group, and that we spend egregiously too much time on our backsides rather than our feet — we might reasonably address only the remaining fraction of the obesity epidemic with other considerations. I am quite confident that residual fraction would be very small.

Which leads back to: We can fix obesity, and it isn’t complicated.

As a culture, we are drowning in calories of mostly very dubious quality, and drowning in an excess of labor-saving technology. I have compared obesity to drowning before, but want to dive more deeply today into the implications for fixing what ails us.

Let’s imagine, first, if we treated drowning the way we treat obesity. Imagine if we had company executives on panels telling us why we can’t really do anything about it today, because it is so enormously complicated. Imagine if we felt we needed panels and committees to do anything about epidemic drowning. Such arguments could be made, of course.

For, you see, drowning is complicated. There is individual variability — some people can hold their breath longer than others. Not all water is the same — there are variations in density, salinity, and temperature. There are factors other than the water — such as why you fell in in the first place, use or neglect of personal flotation devices, and social context. There are factors in the water other than water, from rocks, to nets, to sharks.

The argument could be made that anything like a lifeguard is an abuse of authority and an imposition on personal autonomy, because the prevention of drowning should derive from personal and parental responsibility.

The argument could be made that fences around pools hint at the heavy hand of tyranny, barring our free ambulation and trampling our civil liberties.

We would, if drowning were treated like obesity, call for more personal responsibility, but make no societal effort to impart the power required to take responsibility. In other words, we wouldn’t actually teach anyone how to swim (just as we make almost no systematic effort to teach people to “swim” in a sea of calories and technology).

Were we to treat drowning more like obesity, we would have whole industries devoted to talking people into the choices most likely to harm them — and profiting from those choices. One imagines a sign, courtesy of some highly-paid Madison Avenue consultants: “Awesome rip current: Swim here, and we’ll throw in a free beach towel! (If you ever make it out of the water…)”

If we treated swimming and eating more alike, we would very willfully goad even the youngest children into acts of peril. An announcer near that unfenced pool would call out: “Jump right in, there’s a toy at the bottom of the deep end! And don’t worry, the pool water is fortified with chlorine — part of a healthy lifestyle!”

I could go on, but you get the idea. But you also, I trust, have reservations. As you recognize that treating drowning like obesity would be ludicrous, you must be reflecting on why drowning isn’t like obesity. I’ve done plenty of just such reflecting myself, and here’s my conclusion: time.

The distinction between drowning in water, and how we contend with it, and drowning in calories and sedentariness, is the cause-and-effect timeline. In the case of water, drowning happens more or less immediately, and there is no opportunity to dispute the trajectory from cause to effect. In the case of obesity, there is no immediacy; the drowning takes place over months to years to decades. It’s a bit blurry.

Really, that’s it. If you disagree, tell me the flaw — I promise to listen.

We have the time perception of our ancestors, contending with the immediate threats of predation and violence on the savannas of our origins. We are poorly equipped to perceive calamitous cause-and-effect when it plays out in slow motion. One imagines viewing ourselves through the medium of time-lapse photography, and suddenly seeing the obvious: We topple into the briny, obesigenic depths of modern culture, and emerge obese. Cause and effect on vivid display, no committees required.

Consider how differently we would feel about junk food if it caused obesity or diabetes immediately, rather than slowly. Imagine if you drank a soda, and your waist circumference instantly increased by two inches. It likely will — it’s just a matter of time.

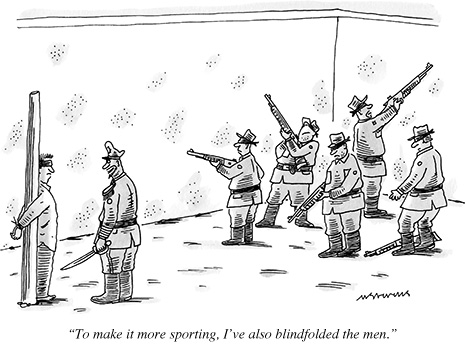

We generally deal effectively with cause-and-effect catastrophes that have the “advantage” of immediacy. One obvious exception comes to mind: gun violence. If the “pool lobby” were to address drowning the way the gun lobby addresses gun violence, the solution would somehow be more pools, fewer fences, and no lifeguards. But that will have to be a rant for another day, so let’s not go down that rabbit hole.

Instead, let’s flip the comparison for a moment. What if saw beyond our Paleolithic perceptions of temporality, recognized the cause-and-effect of epidemic obesity and chronic disease, and treated the scenario just like drowning?

We would, indeed, rely on parental vigilance and responsibility — but not invoke them as an excuse to neglect the counterparts of fences and lifeguards. We would impede, not encourage, children’s access to potentially harmful foods. We would avoid promoting the most dangerous exposures to the most vulnerable people.

We would recognize that just as swimming must be taught, so must swimming rather than drowning in the modern food supply and sea of technology. We would teach these skills systematically and at every opportunity, and do all we could to safeguard those who lack such skills until they acquire them. Swimming is not a matter of willpower; it’s a matter of skill-power. So, too, is eating well and being active in a world that all too routinely washes away opportunities for both.

Your “eye for resemblances” is likely as good as mine, so I leave a full inventory of all the anti-obesity analogues to defenses against drowning to your imagination. They are, of course, there for us: analogues to lifeguards, fences, swimming lessons, warnings against riptides, beach closures, personal responsibility and vigilance, public policies, regulations and restrictions, and a general pattern of conscientious concern by the body politic for the fate of individual bodies.

The only real distinction between drowning in water and drowning in calories related to causality is time. One hurts us immediately, the other hurts us slowly. The other important distinction is magnitude. People do, of course, drown, and it’s tragic when it happens. But obesity and chronic disease affect orders of magnitude more of us, and our children, and rob from us orders of magnitude more years of life, and life in years.

No one with a modicum of sense or a vestige of decency would stand near a pool, watch children topple in one after another, and wring their hands over the dreadfully complicated problem and the need for innumerable committees to contend with it.

We are drowning in copious quantities of poor-quality (even willfully addictive) calories, and labor-saving technologies all too often invented in the absence of need. We have run out of time to see that this is like the other kind of drowning, a clear-cut case of calamitous cause-and-effect, albeit in slower motion, playing out over an extended timeline.

We could fix obesity. It’s hard, because profit and cultural inertia oppose change. But it’s not complicated. (And maybe it isn’t even as hard as we tend to think.)

As we look out at an expanse of bodies sinking beneath the waves of aggressively-marketed junk and pervasive inactivity, wring our hands and contemplate forming more committees — I can’t help but think we’ve gone right off the deep end.

-fin

Dr. David L. Katz; www.davidkatzmd.com

www.turnthetidefoundation.org

The U.S. healthcare system

The U.S. healthcare system