I’ve been absolutely terrified every minute of my life — and i’ve never let it keep me from doing a single thing I wanted to do

Georgia O’Keeffe, 99

Good call…

http://www.medicalobserver.com.au/news/call-to-cap-specialists-fees-gathers-support

Flynn Murphy all articles by this author

THE former Howard government adviser who reignited the co-payment debate is back. In his sights: exorbitant out-of-pocket expenses being charged by overpaid specialists.

Terry Barnes has called for the fees that surgeons and other specialists can charge to be capped at their AMA-recommended rates. And if they charge too much they should be refused access to Medicare, he told Medical Observer.

“If the AMA schedule is considered fair and reasonable, then any out-of-pocket in excess of that is, by definition, unreasonable,” Mr Barnes said.

“What I propose is that if the government gives ground on cutting the GP rebate [for the co-payment], the quid pro quo is that the government works together with the AMA to reduce patient out-of-pockets.”

Mr Barnes showed MO a recent anaesthetist’s bill that saw him pay four times the rebate he was entitled to under the MBS.

“She should have delivered an anaesthetic with her [bill],” he said.

The proposal is backed by the Grattan Institute’s Dr Stephen Duckett, a prominent health economist who gave evidence to the recent Senate inquiry into out-of-pocket costs.

In his submission to the inquiry, Dr Duckett reported that for people in the lowest disposable income decile, average fees for specialists were nearly four times the average GP fee.

“I think it’s a good idea,” he said of Mr Barnes’s call.

“I think the profession has to have some responsibility for moderating out-of-pocket costs. There is an issue here about professional responsibility.”

The comments follow a statement from the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (RACS) expressing concern about reports of “excessive… even extortionate” and “unethical” surgical fees being charged to patients by its own members.

RACS president Professor Michael Grigg said the reported fees were “damaging to the health system and to the standing of surgeons and the surgical profession”.

“RACS believes that extortionate fees, where they are manifestly excessive and bear little if any relationship to utilisation of skills, time or resources, are exploitative and unethical. As such, they are in breach of the college’s code of conduct and will be dealt with by the college,” the statement said.

But an RACS spokesman said the college does not support a cap on fees.

An AMA spokesman said: “The AMA is currently in talks with the government on the disastrous and hugely unpopular budget co-payments proposal, and doubts that the government would be rushing to adopt any other ‘thought bubbles’ from the author of that policy.”

I like these… good for provoking a reaction…

https://www.linkedin.com/today/post/article/20140807094555-20017018-13-ceos-share-their-favorite-job-interview-questions

Interview questions: Everyone has them.

And everyone wishes they had better ones.

So I asked smart people from a variety of fields for their favorite interview question and what it tells them about the candidate.

1. Why have you had X number of jobs in Y years?

This question helps me get a full picture of the candidate’s work history. What keeps them motivated? Why, if they have, did they jump from job to job? And what is the key factor when they leave?

The answer shows me their loyalty and their reasoning process. Do they believe someone always keeps them down (managers, bosses, etc.)? Do they get bored easily?

There is nothing inherently wrong with moving from job to job — the reasons why are what matters.

— Shama Kabani, The Marketing Zen Group founder and CEO

2. If we’re sitting here a year from now celebrating what a great twelve months it’s been for you in this role, what did we achieve together?

For me, the most important thing about interviews is that the interviewee interviews us. I need to know they’ve done their homework, truly understand our company and the role… and reallywant it.

The candidate should have enough strategic vision to not only talk about how good the year has been but to answer with an eye towards that bigger-picture understanding of the company — and why they want to be here.

— Randy Garutti, Shake Shack CEO

3. When have you been most satisfied in your life?

Except with entry-level candidates, I presume reasonable job skill and intellect. Plus I believe smart people with relevant experience adapt quickly and excel in new environments where the culture fits and inspires them. So, I concentrate on character and how well theirs matches that of my organization.

This question opens the door for a different kind of conversation where I push to see the match between life in my company and what this person needs to be their best and better in my company than he or she could be anywhere else.

— Dick Cross, Cross Partnership founder and CEO

4. If you got hired, loved everything about this job, and are paid the salary you asked for, what kind of offer from another company would you consider?

I like to find out how much the candidate is driven by money versus working at a place they love.

Can they be bought?

You’d be surprised by some of the answers.

— Ilya Pozin, Ciplex founder

5. Who is your role model, and why?

The question can reveal how introspective the candidate is about their own personal and professional development, which is a quality I have found to be highly correlated with success and ambition.

Plus it can show what attributes and behaviors the candidate aspires to.

— Clara Shih, Hearsay Social co-founder and CEO

6. What things do you not like to do?

We tend to assume people who have held a role enjoy all aspects of that role, but I’ve found that is seldom the case.

Getting an honest answer to the question requires persistence, though. I usually have to ask it a few times in different ways, but the answers are always worth the effort. For instance, I interviewed a sales candidate who said she didn’t enjoy meeting new people.

My favorite was the finance candidate who told me he hated dealing with mundane details and checking his work. Next!

— Art Papas, Bullhorn founder and CEO

7. Tell me about a project or accomplishment that you consider to be the most significant in your career.

I find that this question opens the door to further questions and enables someone to highlight themselves in a specific, non-generic way.

Plus additional questions can easily follow: What position did you hold when you achieved this accomplishment? How did it impact your growth at the company? Who else was involved and how did the accomplishment impact your team?

Discussing a single accomplishment is an easy way to open doors to additional information and insight about the person, their work habits, and how they work with others.

— Deborah Sweeney, MyCorporation CEO

8. What’s your superpower… or spirit animal?

During her interview I asked my current executive assistant what was her favorite animal. She told me it was a duck, because ducks are calm on the surface and hustling like crazy getting things done under the surface.

I think this was an amazing response and a perfect description for the role of an EA. For the record, she’s been working with us for over a year now and is amazing at her job.

— Ryan Holmes, HootSuite CEO

9. We’re constantly making things better, faster, smarter or less expensive. We leverage technology or improve processes. In other words, we strive to do more–with less. Tell me about a recent project or problem that you made better, faster, smarter, more efficient, or less expensive.

Good candidates will have lots of answers to this question. Great candidates will get excited as they share their answers.

In 13 years we’ve only passed along one price increase to our customers. That’s not because our costs have decreased–quite the contrary. We’ve been able to maintain our prices because we’ve gotten better at what we do. Our team, at every level, has their ears to the ground looking for problems to solve.

Every new employee needs to do that, too.

— Edward Wimmer, RoadID co-founder

10. Discuss a specific accomplishment you’ve achieved in a previous position that indicates you will thrive in this position.

Past performance is usually the best indicator of future success.

If the candidate can’t point to a prior accomplishment, they are unlikely to be able to accomplish much at our organization–or yours.

–– Dave Lavinsky, founder of Guiding Metrics

11. So, what’s your story?

This inane question immediately puts an interviewee on the defensive because there is no right answer or wrong answer. But there is an answer.

It’s a question that asks for a creative response. It’s an invitation to the candidate to play the game and see where it goes without worrying about the right answer. By playing along, it tells me a lot about the character, imagination, and inventiveness of the person.

The question, as obtuse as it might sound to the interviewee, is the beginning of a story and in today’s world of selling oneself, or one’s company, it’s the ability to tell a story and create a feeling that sells the brand–whether it’s a product or a person.

The way they look at me when the question is asked also tells me something about their likeability. If they act defensive, look uncomfortable, and pause longer than a few seconds, it tells me they probably take things too literally and are not broad thinkers. In our business we need broad thinkers.

— Richard Funess, Finn Partners managing partner

12. What questions do you have for me?

I love asking this question really early in the interview–it shows me whether the candidate can think quickly on their feet, and also reveals their level of preparation and strategic thinking.

I often find you can learn more about a person based on the questions they ask versus the answers they give.

— Scott Dorsey, ExactTarget co-founder and CEO

13. Tell us about a time when things didn’t go the way you wanted — like a promotion you wanted and didn’t get, or a project that didn’t turn out how you had hoped.

It’s a simple question that says so much. Candidates may say they understand the importance of working as a team but that doesn’t mean they actually know how to work as a team. We need self-starters that will view their position as a partnership.

Answers tend to fall into three basic categories: 1) blame 2) self-deprecation, or 3) opportunity for growth.

Our company requires focused employees willing to wear many hats and sometimes go above and beyond the job description, so I want team players with the right attitude and approach. If the candidate points fingers, blames, goes negative on former employers, communicates with a sense of entitlement, or speaks in terms of their role as an individual as opposed to their position as a partnership, he or she won’t do well here.

But if they take responsibility and are eager to put what they have learned to work, they will thrive in our meritocracy.

— Tony Knopp, Spotlight Ticket Management co-founder and CEO

http://www.economist.com/news/international/21608767-patients-around-world-are-starting-give-doctors-piece-their-mind-result?fsrc=scn/tw_ec/docadvisor

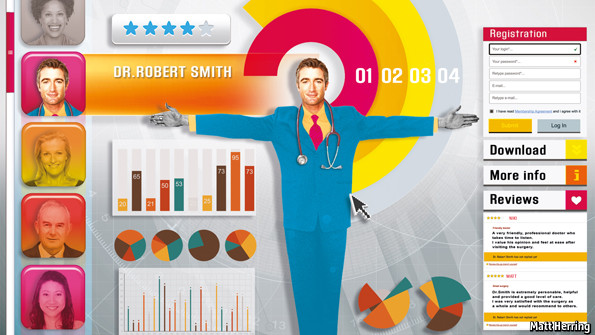

WHEN a patient in Illinois did not like the result of her breast-augmentation surgery, she reacted like many dissatisfied customers: by writing negative comments about her doctor on websites that feature such reviews. Her breasts, she said, looked like something out of a horror movie. Other unhappy patients joined her online, calling the doctor “dangerous”, “horrible” and a “jackass”. He sued them for defamation. (The cases were later dropped.)

Other doctors have filed similar lawsuits, mostly in America. Though few have won, their reaction illustrates a discomfort with patient reviews felt by many of their colleagues. Some question the accuracy and relevance of the feedback; others complain that privacy rules prevent them from responding. Sites often have just a handful of ratings per doctor, meaning results can be skewed by a single bad write-up.

But increasingly, doctors cannot afford to ignore them. They often lead the results of searches for doctors’ names. In America, the world’s biggest health-care market, firms that offer health insurance are making employees pay a bigger share, pushing them to search for guidance online. The most sophisticated sites are attracting more users by including reviews and other features. ZocDoc also lets patients make appointments. Offerings from Vitals include a quality indicator it has built using data from 170,000-odd sources. Castlight Health includes prices gathered from insurance bills and other data. The differences can be startling—the cost of a brain scan in Philadelphia ranges from $264 to $3,271.

With around 60 review sites, America leads the way. But they are also popping up in other countries where patients pay for at least part of their care. Practo, an Indian firm that schedules appointments with doctors, plans to start publishing patients’ reviews later this year. More and more Chinese patients, who generally do not have a regular family doctor, are using a site run by Hao Dai Fu (“good doctor”) to navigate their country’s unstructured health system, says Haijing Hao of the University of Massachusetts. It has profiles of around 300,000 doctors and over 1m reviews.

Increasingly, doctors, hospitals and health systems are seeking to turn the trend to their advantage. Some now offer incentives, such as prize draws, for patients to go online and rate them. A survey by ZocDoc found that 85% of doctors on its site looked at their ratings last year. And a handful of health-care providers have even started to publish reviews themselves. The University of Utah, which runs four hospitals and ten clinics, was one of the first, in 2012. Its doctors’ complaints about independent sites encouraged it to publish patient feedback that was already being collected for internal use. Some of its doctors now have hundreds of reviews.

Preparing staff for the publication of all the comments, good and bad, took a year, says Brian Gresh, who helped create the university’s system. But their worries appear to have been groundless: most reviews are positive, and patient-satisfaction scores improved after the move. Happy patients communicate and co-operate better with their doctors, says Tom Lee, the chief medical officer of Press Ganey, a firm that surveys patients on behalf of health-care providers, including for the University of Utah. Its boss, Pat Ryan, predicts that plenty of other hospitals will follow suit.

Some doctors are still sceptical, fearing, for example, that patients may judge a hospital on its decor rather than its care. But patients are rarely swayed much by such trivia, insists Mr Ryan: “If you have flat-screen televisions and your communication is poor, you will get very bad scores.” Moreover, the feedback reminds doctors that every meeting with a patient matters, so they try harder.

America’s government has started to link health-care payments with patient feedback: Medicare, a federal scheme for over-65s, recently started to give bonuses to hospitals that score well. The Cleveland Clinic, a big hospital, uses these data to improve its care. Britain’s National Health Service has surveyed patients for over a decade (though not on the performance of individual doctors) and published the results online—though some think it could use its findings better.

But many other governments do not even ask patients for their opinions. German doctors and hospitals, for example, have fought efforts to link funding with quality of care, says Maria Nadj-Kittler of the Picker Institute Europe, a research organisation, and are therefore hostile to patient reviews. This is a missed opportunity. Patients who hold their doctors accountable make them better and more efficient. That is good news no matter who pays.

So pay for performance doesn’t work. This is hardly surprising when you see the compromise and mediocrity forced upon policy makers to get ideas through. There have been instances of success in health care. Indeed, one could argue that the exemplary success of big pharma in changing physician behaviour has provided a rod for its own back. Why not harness this expertise in getting under the skin of doctors, and pay big pharma sales outfits to guide physician practice in constructive directions, rather than being distracted by flogging pills that don’t really work that well anyway, and potentially harm? Might have a chat with Christian.

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/29/upshot/the-problem-with-pay-for-performance-in-medicine.html

“Pay for performance” is one of those slogans that seem to upset no one. To most people it’s a no-brainer that we should pay for quality and not quantity. We all know that paying doctors based on the amount of care they provide, as we do with a traditional fee-for-service setup, creates incentives for them to give more care. It leads to increased health care spending. Changing the payment structure to pay them for achieving goals instead should reduce wasteful spending.

So it’s no surprise that pay for performance has been an important part of recent reform efforts. But in reality we’re seeing disappointingly mixed results. Sometimes it’s because providers don’t change the way they practice medicine; sometimes it’s because even when they do, outcomes don’t really improve.

The idea behind pay for performance is simple. We will give providers more money for achieving a goal. The goal can be defined in various ways, but at its heart, we want to see the system hit some target. This could be a certain number of patients receiving preventive care, a certain percentage of people whose chronic disease is being properly managed or even a certain number of people avoiding a bad outcome. Providers who reach these targets earn more money.

The problem, one I’ve noted before, is that changing physician behavior is hard. Sure, it’s possible to find a study in the medical literature that shows that pay for performance worked in some small way here or there. For instance, a study published last fall found that paying doctors $200 more per patient for hitting certain performance criteria resulted in improvements in care. It found that the rate of recommendations for aspirin or for prescriptions for medications to prevent clotting for people who needed it increased 6 percent in clinics without pay for performance but 12 percent in clinics with it.

Good blood pressure control increased 4.3 percent in clinics without pay for performance but 9.7 percent in clinics with it. But even in the pay-for-performance clinics, 35 percent of patients still didn’t have the appropriate anti-clotting advice or prescriptions, and 38 percent of patients didn’t have proper hypertensive care. And that’s success!

It’s also worth noting that the study was only for one year, and many improvements in actual outcomes would need to be sustained for much longer to matter. It’s not clear whether that will happen. A study published in Health Affairs examined the effects of a government partnership with Premier Inc., a national hospital system, and found that while the improvements seen in 260 hospitals in a pay-for-performance project outpaced those of 780 not in the project, five years later all those differences were gone.

The studies showing failure are also compelling. A study in The New England Journal of Medicine looked at 30-day mortality in the hospitals in the Premier pay-for-performance program compared with 3,363 hospitals that weren’t part of a pay-per-performance intervention. We’re talking about a study of millions of patients taking place over a six-year period in 12 states. Researchers found that 30-day mortality, or the rate at which people died within a month after receiving certain procedures or care, was similar at the start of the study between the two groups, and that the decline in mortality over the next six years was also similar.

Moreover, they found that even among the conditions that were explicitly linked to incentives, like heart attacks and coronary artery bypass grafts, pay for performance resulted in no improvements compared with conditions without financial incentives.

In Britain, a program was begun over a decade ago that would pay general practitioners up to 25 percent of their income in bonuses if they met certain benchmarks in the management of chronic diseases. The program made no difference at all in physician practice or patient outcomes, and this was with a much larger financial incentive than most programs in the United States offer.

Even refusing to pay for bad outcomes doesn’t appear to work as well as you might think. A 2012 study published in The New England Journal of Medicine looked at how the 2008 Medicare policy to refuse to pay for certain hospital-acquired conditions affected the rates of such infections. Those who devised the policy imagined that it would lead hospitals to improve their care of patients to prevent these infections. That didn’t happen. The policy had almost no measurable effect.

There have even been two systematic reviews in this area. The first of them suggested that there is some evidence that pay for performance could change physicians’ behavior. It acknowledged, though, that the studies were limited in how they could be generalized and might not be able to be replicated. It also noted there was no evidence that pay for performance improved patient outcomes, which is what we really care about. The secondreview found that with respect to primary care physicians, there was no evidence that pay for performance could even change physician behavior, let alone patient outcomes.

One of the reasons that paying for quality is hard is that we don’t even really know how to define “quality.” What is it, really? Far too often we approach quality like a drunkard’s search, looking where it’s easy rather than where it’s necessary. But it’s very hard to measure the things we really care about, like quality of life and improvements in functioning.

In fact, the way we keep setting up pay for performance demands easy-to-obtain metrics. Otherwise, the cost of data gathering could overwhelm any incentives. Unfortunately, as a recent New York Times article described, this has drawbacks.

The National Quality Forum, described in the article as an influential nonprofit, nonpartisan organization that endorses health care standards, reported that the metrics chosen by Medicare for their programs included measurements that were outside the control of a provider. In other words, factors like income, housing and education can affect the metrics more than what doctors and hospitals do.

This means that hospitals in resource-starved settings, caring for the poor, might be penalized because what we measure is out of their hands. A panel commissioned by the Obama administration recommended that the Department of Health and Human Services change the program to acknowledge the flaw. To date, it hasn’t agreed to do so.

Some fear that pay for performance could even backfire. Studies in other fields show that offering extrinsic rewards (like financial incentives) can undermine intrinsic motivations (like a desire to help people). Many physicians choose to do what they do because of the latter. It would be a tragedy if pay for performance wound up doing more harm than good.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qHQWlFtSptU

AMA at its best (worst).

It doesn’t want price transparency because its too hard to predict how much things should cost charging by the hour instead of by the procedure.

I’d want to know more about my surgeon than my dishwasher when making a purchasing decision.

So lets put up all those metrics and allow people to compare what matters.

http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/political-news/ama-rejects-call-for-more-fee-disclosure-20140729-3cs2y.html#ixzz396F0w0H6

AMA president Brian Owler at the National Press Club in Canberra on Wednesday. Photo: Alex Ellinghausen

The Australian Medical Association has rejected calls for greater transparency on surgical fees, saying it was not possible for patients to compare prices for operations in the same way they might shop around for a dishwasher.

Appearing at a Senate hearing on Tuesday, AMA president Brian Owler, who is a neurosurgeon, said his organisation did not support the charging of excessive fees, but said the appropriate fee for a procedure depended on the patient’s condition.

”It is not possible to put up on a website all of our fees … and be able to go, like you’re buying a dishwasher, and be able to work out which doctor you’re going to on the basis of the fee that they charge,” Associate Professor Owler said.

”The experience and qualifications of many of the doctors will vary, their practices will vary, and really you need to see a patient to understand what their problem is, then formulate with that patient the best plan of management.”

Professor Owler’s comments follow a statement from the Australasian College of Surgeons in which it expressed concern about some surgeons, including some of its own members, charging ”extortionate” fees.

The president of the college, Michael Grigg, said it was working with the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission on ways to allow greater disclosure of surgeons’ fees without breaching competition rules.

Prominent neurosurgeon Charlie Teo said there were some surgeons who abused the ignorance of their patients.

But he said the recommended fee for some procedures, such as the approximately $2500 fee for the removal of a brain tumour, undervalued the work involved in complex cases.

”I can be operating on the world’s most difficult brain tumour and it takes eight to 10 hours and I still get paid $2500. Versus a plastic surgeon who charges $8000 to $12,000 for a breast augmentation,” Dr Teo said.

Dr Teo recommended Australia adopt a the American Medical Association’s ”22 Modifier” policy, which requires surgeons to supply evidence that the service provided was substantially greater than the work typically required for a certain procedure if they charged higher fees.

Greens senator Richard Di Natale, who initiated the Senate inquiry into out-of-pocket health costs, said patients needed greater transparency on costs.

”At the moment, the problem is that people become aware of the out-of-pocket costs when it’s too late, when they’re well advanced down the treatment pathway, and often there’s no way of turning back.”

The president of the Australian Society of Plastic Surgeons, Tony Kane, said its members were required to make a full written disclosure to patients of what the cost of their treatment would be, including the possibility of further costs, should revision surgery be necessary.

Dr Kane said members were required to make this disclosure at a sufficiently early stage to enable patients to take cost considerations into account when deciding whether to undergo the treatment.