Great tip from Michael Griffith on the back of last night’s dinner terrific conversation at the Nicholas Gruen organised feast at Hellenic Republic…

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-03-12/your-job-taught-to-machines-puts-half-u-s-work-at-risk.html

Paper (PDF): The_Future_of_Employment

Your Job Taught to Machines Puts Half U.S. Work at Risk

Who needs an army of lawyers when you have a computer?

When Minneapolis attorney William Greene faced the task of combing through 1.3 million electronic documents in a recent case, he turned to a so-called smart computer program. Three associates selected relevant documents from a smaller sample, “teaching” their reasoning to the computer. The software’s algorithms then sorted the remaining material by importance.

“We were able to get the information we needed after reviewing only 2.3 percent of the documents,” said Greene, a Minneapolis-based partner at law firm Stinson Leonard Street LLP.

Full Coverage: Technology and the Economy

Artificial intelligence has arrived in the American workplace, spawning tools that replicate human judgments that were too complicated and subtle to distill into instructions for a computer. Algorithms that “learn” from past examples relieve engineers of the need to write out every command.

The advances, coupled with mobile robots wired with this intelligence, make it likely that occupations employing almost half of today’s U.S. workers, ranging from loan officers to cab drivers and real estate agents, become possible to automate in the next decade or two, according to a study done at the University of Oxford in the U.K.

Aethon Inc.’s self-navigating TUG robot transports soiled linens, drugs and meals in…Read More

“These transitions have happened before,” said Carl Benedikt Frey, co-author of the study and a research fellow at the Oxford Martin Programme on the Impacts of Future Technology. “What’s different this time is that technological change is happening even faster, and it may affect a greater variety of jobs.”

Profound Imprint

It’s a transition on the heels of an information-technology revolution that’s already left a profound imprint on employment across the globe. For both physical andmental labor, computers and robots replaced tasks that could be specified in step-by-step instructions — jobs that involved routine responsibilities that were fully understood.

That eliminated work for typists, travel agents and a whole array of middle-class earners over a single generation.

Yet even increasingly powerful computers faced a mammoth obstacle: they could execute only what they’re explicitly told. It was a nightmare for engineers trying to anticipate every command necessary to get software to operate vehicles or accurately recognize speech. That kept many jobs in the exclusive province of human labor — until recently.

Oxford’s Frey is convinced of the broader reach of technology now because of advances in machine learning, a branch of artificial intelligence that has software “learn” how to make decisions by detecting patterns in those humans have made.

Artificial intelligence has arrived in the American workplace, spawning tools that… Read More

702 Occupations

The approach has powered leapfrog improvements in making self-driving cars and voice search a reality in the past few years. To estimate the impact that will have on 702 U.S. occupations, Frey and colleague Michael Osborne applied some of their own machine learning.

They first looked at detailed descriptions for 70 of those jobs and classified them as either possible or impossible to computerize. Frey and Osborne then fed that data to an algorithm that analyzed what kind of jobs make themselves to automation and predicted probabilities for the remaining 632 professions.

The higher that percentage, the sooner computers and robots will be capable of stepping in for human workers. Occupations that employed about 47 percent of Americans in 2010 scored high enough to rank in the risky category, meaning they could be possible to automate “perhaps over the next decade or two,” their analysis, released in September, showed.

Safe Havens

“My initial reaction was, wow, can this really be accurate?” said Frey, who’s a Ph.D. economist. “Some of these occupations that used to be safe havens for human labor are disappearing one by one.”

Loan officers are among the most susceptible professions, at a 98 percent probability, according to Frey’s estimates. Inroads are already being made by Daric Inc., an online peer-to-peer lender partially funded by former Wells Fargo & Co. Chairman Richard Kovacevich. Begun in November, it doesn’t employ a single loan officer. It probably never will.

The startup’s weapon: an algorithm that not only learned what kind of person made for a safe borrower in the past, but is also constantly updating its understanding of who is creditworthy as more customers repay or default on their debt.

It’s this computerized “experience,” not a loan officer or a committee, that calls the shots, dictating which small businesses and individuals get financing and at what interest rate. It doesn’t need teams of analysts devising hypotheses and running calculations because the software does that on massive streams of data on its own.

Lower Rates

The result: An interest rate that’s typically 8.8 percentage points lower than from a credit card, according to Daric. “The algorithm is the loan officer,” said Greg Ryan, the 29-year-old chief executive officer of the Redwood City, California, company that consists of him and five programmers. “We don’t have overhead, and that means we can pass the savings on to our customers.”

Similar technology is transforming what is often the most expensive part of litigation, during which attorneys pore over e-mails, spreadsheets, social media posts and other records to build their arguments.

Each lawsuit was too nuanced for a standard set of sorting rules, and the string of keywords lawyers suggested before every case still missed too many smoking guns. The reading got so costly that many law firms farmed out the initial sorting to lower-paid contractors.

Training Software

The key to automate some of this was the old adage to show not tell — to have trained attorneys illustrate to the software the kind of documents that make for gold. Programs developed by companies such as San Francisco-based Recommind Inc. then run massive statistics to predict which files expensive lawyers shouldn’t waste their time reading. It took Greene’s team of lawyers 600 hours to get through the 1.3 million documents with the help of Recommind’s software. That task, assuming a speed of 100 documents per hour, could take 13,000 hours if humans had to read all of them.

“It doesn’t mean you need zero people, but it’s fewer people than you used to need,” said Daniel Martin Katz, a professor at Michigan State University’s College of Law in East Lansing who teaches legal analytics. “It’s definitely a transformation for getting people that first job while they’re trying to gain additional skills as lawyers.”

Robot Transporters

Smart software is transforming the world of manual labor as well, propelling improvements in autonomous cars that make it likely machines can replace taxi drivers and heavy truck drivers in the next two decades, according to Frey’s study.

One application already here: Aethon Inc.’s self-navigating TUG robots that transport soiled linens, drugs and meals in now more than 140 hospitals predominantly in the U.S. When Pittsburgh-based Aethon first installs its robots in new facilities, humans walk the machines around. It would have been impossible to have engineers pre-program all the necessary steps, according to Chief Executive Officer Aldo Zini.

“Every building we encounter is different,” said Zini. “It’s an infinite number” of potential contingencies and “you could never ahead of time try to program everything in. That would be a massive effort. We had to be able to adapt and learn as we go.”

Human-level Cognition

To be sure, employers won’t necessarily replace their staff with computers just because it becomes technically feasible to do so, Frey said. It could remain cheaper for some time to employ low-wage workers than invest in expensive robots. Consumers may prefer interacting with people than with self-service kiosks, while government regulators could choose to require human supervision of high-stakes decisions.

Even more, recent advances still don’t mean computers are nearing human-level cognition that would enable them to replicate most jobs. That’s at least “many decades” away, according to Andrew Ng, director of the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Laboratory near Palo Alto, California.

Machine-learning programs are best at specific routines with lots of data to train on and whose answers can be gleaned from the past. Try getting a computer to do something that’s unlike anything it’s seen before, and it just can’t improvise. Neither can machines come up with novel and creative solutions or learn from a couple examples the way people can, said Ng.

Employment Impact

“This stuff works best on fairly structured problems,” said Frank Levy, a professor emeritus at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge who has extensively researched technology’s impact on employment. “Where there’s more flexibility needed and you don’t have all the information in advance, it’s a problem.”

That means the positions of Greene and other senior attorneys, whose responsibilities range from synthesizing persuasive narratives to earning the trust of their clients, won’t disappear for some time. Less certain are prospects for those specializing in lower-paid legal work like document reading, or in jobs that involve other relatively repetitive tasks.

As more of the world gets digitized and the cost to store and process that information continues to decline, artificial intelligence will become even more pervasive in everyday life, says Stanford’s Ng.

“There will always be work for people who can synthesize information, think critically, and be flexible in how they act in different situations,” said Ng, also co-founder of online education provider Coursera Inc. Still, he said, “the jobs of yesterday won’t the same as the jobs of tomorrow.”

Workers will likely need to find vocations involving more cognitively complex tasks that machines can’t touch. Those positions also typically require more schooling, said Frey. “It’s a race between technology and education.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Aki Ito in San Francisco at aito16@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Chris Wellisz at cwellisz@bloomberg.net Gail DeGeorge, Mark Rohner

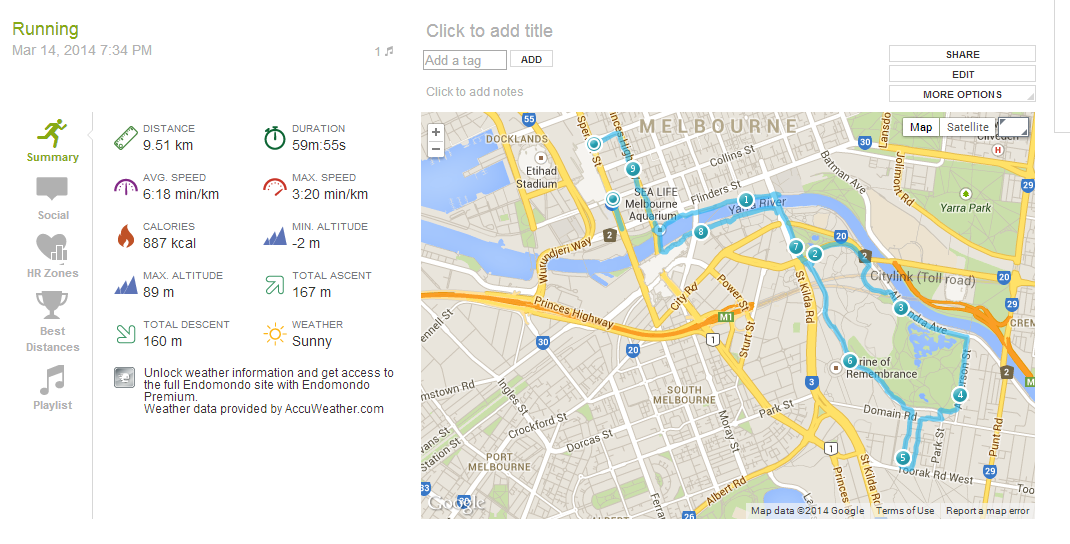

Albert Sun: I think it started with a really simple graphic that my colleague Alastair put together last year listing a few interesting wearable health monitors and what things they measured. For that he put together this google spreadsheet and we sort of tried to keep it up to date with all the different gadgets as we heard about them. I was constantly adding things to it and at a point felt that if I was having this much trouble keeping track of all of them that probably other people were as well. My original idea was actually to put them all to the test in accuracy and be able to chart which ones were the most accurate. I had plans to reverse engineer their drivers and access the raw data they were recording. But once I actually started wearing them I realized that, yes there was a lot of data, but it was actually this idea of motivation and behavior change and how you understand the data that was much more interesting.

Albert Sun: I think it started with a really simple graphic that my colleague Alastair put together last year listing a few interesting wearable health monitors and what things they measured. For that he put together this google spreadsheet and we sort of tried to keep it up to date with all the different gadgets as we heard about them. I was constantly adding things to it and at a point felt that if I was having this much trouble keeping track of all of them that probably other people were as well. My original idea was actually to put them all to the test in accuracy and be able to chart which ones were the most accurate. I had plans to reverse engineer their drivers and access the raw data they were recording. But once I actually started wearing them I realized that, yes there was a lot of data, but it was actually this idea of motivation and behavior change and how you understand the data that was much more interesting.

Graphic

Graphic