…with some help from SRL. The last par nails it:

Withdrawing from measures we know will work in order to fund new measures we think might work seems a daft way to manage our health. But it’ll help cut the deficit.

http://www.smh.com.au/comment/when-deep-cuts-are-not-healthy-20140602-zrukf.html

When deep cuts are not healthy

Illustration: Andrew Dyson.

It took Mark Latham to say the unsayable. “If a cure to cancer is to be found, most likely it will happen in Europe or the United States,” he wrote in the Weekend Financial Review. Spending scarce funds to find a cure ourselves is a waste of money, a political fig leaf to cover the electoral pain of the GP co-payment.

Anyone who doubts that the Medical Research Future Fund is a fig leaf or an afterthought, needs to only look at the pattern of leaks and speeches leading up to the budget. Ministers spoke often about the need to restrain the cost of Medicare, scarcely at all about the need to boost medical research.

They weren’t able to prepare the way for the medical research future fund because it didn’t come first. It isn’t that pharmaceutical benefits, doctors rebates and future hospital funding are being cut to pay for the fund. It’s that the fund was evoked late in the piece to smooth the edges of the cuts.

Under the descriptions of 23 separate cuts in the budget are the words: “The savings from this measure will be invested by the government in the Medical Research Future Fund”.

The cuts hit dental health, mental health, funding for eye examinations, measures to improve diagnostic images, research into preventive health, a trial of e-health and $55 billion of hospital funding over the next 10 years.

We’re told the cuts are to build a $20 billion Medical Research Future Fund, but the immediate purpose is to cut the deficit.

The wonders of budget accounting mean that the savings notionally allocated to the fund will actually be used to bring down the budget deficit except for when money is withdrawn from the fund to pay for research.

It’s the same trick Peter Costello pulled with the Future Fund. The government gets two gold stars for the price of one. It can both cut the deficit and build up the funds for medical research. And it isn’t yet too sure about what type of research.

Under questioning by senators on Monday, health department officials revealed that they didn’t even know about the fund until late in the budget process and even then provided no advice on how it would work.

Asked about the kind of things the fund would finance, the department’s secretary Jane Halton said the questions were hypothetical.

Would it include evaluations of potentially life-saving preventive health measures such as SunSmart and anti-tobacco programs? “I think it’s unlikely based on the description I have seen, but again we are in an area that we probably can’t yet answer,” she replied.

A few minutes later she asked for her words to be expunged saying she really didn’t know. “We need to work through this level of detail” she told the senators.

We know that cures for cancer, Alzheimer’s and heart disease will be part of fund’s remit, because the Treasurer told us so. “One day someone will find a cure for cancer,” he said after the budget. “Let it be an Australian and let it be us investing in our own health care.”

Latham’s point is that the idea is silly. By all means contribute proportionately to a global effort to find cures for diseases, but don’t try and lead the pack by taking scarce dollars away from applying the medical lessons we have already learnt.

Small countries like Australia are for the most part users rather than creators of technology, and our funds are limited as Joe Hockey well knows.

The Medical Journal of Australia isn’t fooled. This month’s editorial says a government genuinely concerned about extending the working lives of Australians would be investing more in preventing chronic disease, not less.

“The direct effects of the proposed federal budget on prevention include cuts to funding for the National Partnership Agreement on Preventive Health, loss of much of the money previously administered through the now-defunct Australian National Preventive Health Agency, and reductions in social media campaigns, for example, on smoking cessation,” it says.

“Increased funding for bowel cancer screening, the Sporting Schools initiative, the proposed National Diabetes Strategy and for dementia research are positive developments, but do not balance the losses.”

It’s the indirect effects of the measures the fund seeks to make palatable that have it really worried. The $7 co-payment will work out at $14 for patients with chronic diseases. They’ll pay once to see the doctor and then again to have a test. The editorial quoted four studies which have each found that visits for preventive reasons are the ones co-payments are most likely to cut back.

“The effects of these co-payments on preventive behaviour are greatest among those who can least afford the additional costs,” it observes. Which is a pity because “the potential for prevention is greatest among poorer patients, who are often at a health disadvantage”.

We’ll all suffer if co-payments cut vaccination rates, even those of us who aren’t poor, and even if the Medical Research Future Fund finds a cure cancer.

The journal’s biggest concern is that the cuts to hospital services will hit preventive health measures because they are seen as less urgent.

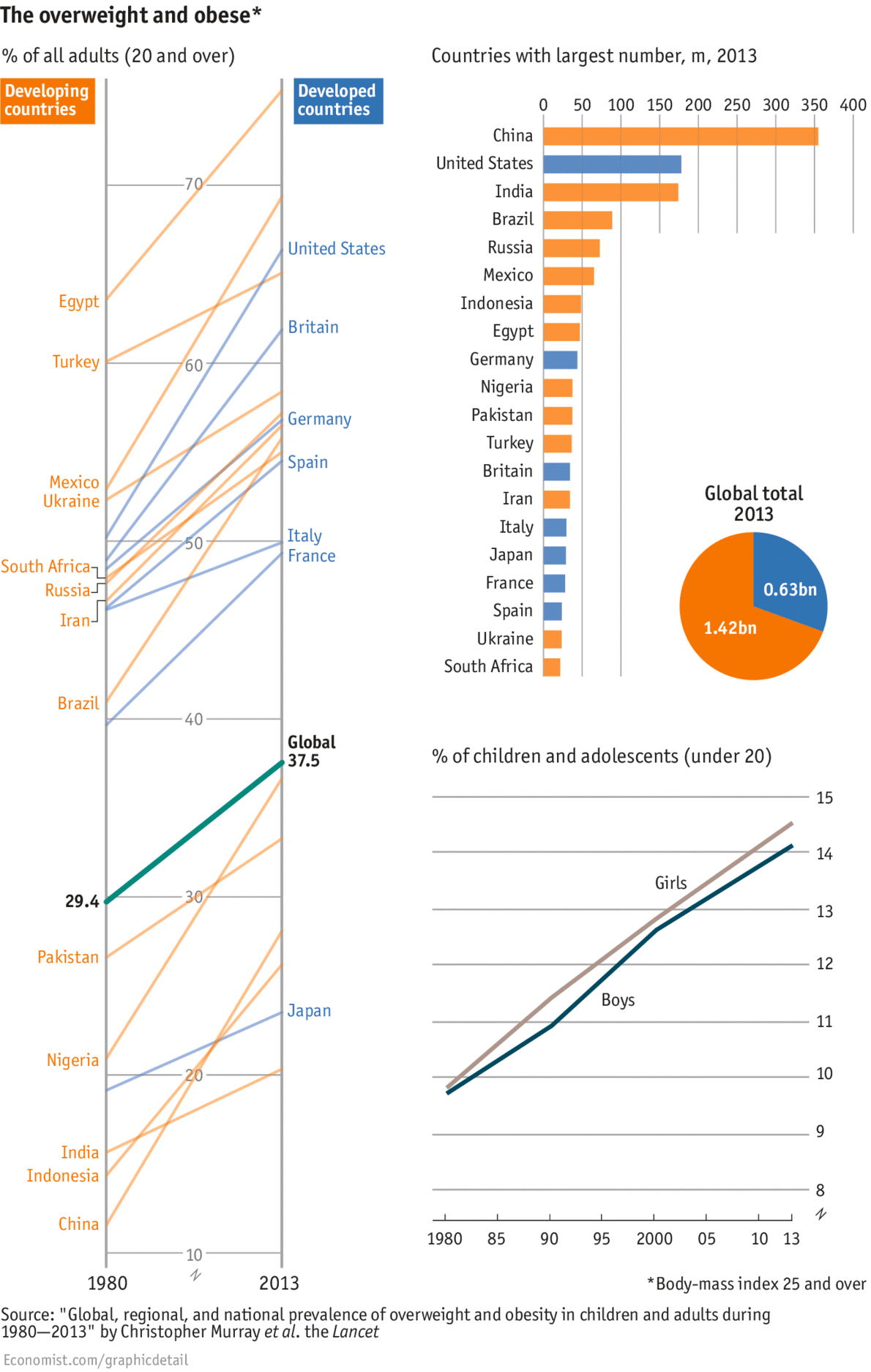

“The greatest pity of all is that the proposed cuts to funding for health come at the time when the first evidence is at hand of potential benefits of the large-scale preventive programs implemented under the national partnership agreements,” the journal writes. “A slowing in the rate of increase in childhood obesity and reductions in smoking rates among indigenous populations have been hard-won achievements.”

Withdrawing from measures we know will work in order to fund new measures we think might work seems a daft way to manage our health. But it’ll help cut the deficit.

Peter Martin is economics editor of The Age.

Twitter: @1petermartin