The HICCup experiment: Manifesto

Just imagine:

It’s 2019 and the mayor is having a bad day. She wants to spearhead a new community program for bike-sharing, but she’s not sure the town can afford it. Meanwhile, one of the new council members is pushing for an overhaul of the school lunch program. She sighs as the assistant deputy mayor walks in. “What now, Henry?” she asks with a slight edge in her voice. But Henry is cheerful: “Mayor, I think we may have a way to fix this. I was just reading about the HICCup Experiment in a town just like ours…. It seems that if we did both the bike program and the school lunches, and made some other changes..”

“But what about our rising health care costs?” asks the mayor.

“That’s the point,” says Henry. “HICCup showed that we can actually reduce those costs if we do multiple interventions simultaneously…even though none of them by itself would make a difference. And there’s an investment banker who just called us that’s eager to work with us to finance the project. They’re asking us to set up a meeting with the big employers and Mercy Saints Health. Using the HICCup data, they think they can finance it all out of the health-care cost savings that would result, as long as we commit to following certain protocols.”

And the vision:

Now it’s 2040. The mayor’s teen-aged son, also called Henry, is discussing his history project on the HICCup Experiment with other members of his MOOC. “Of course,” he concludes, “the HICCup Experiment proved that multiple interventions can dramatically include the overall health of a community. But the Experiment itself wouldn’t work anymore, as a funding vehicle.”

“Why not?” asks Susan, who clearly hasn’t done her homework.

Henry responds patiently with the obvious answer: “Because there are very few places with inflated, unnecessary health care costs anymore.”

The background

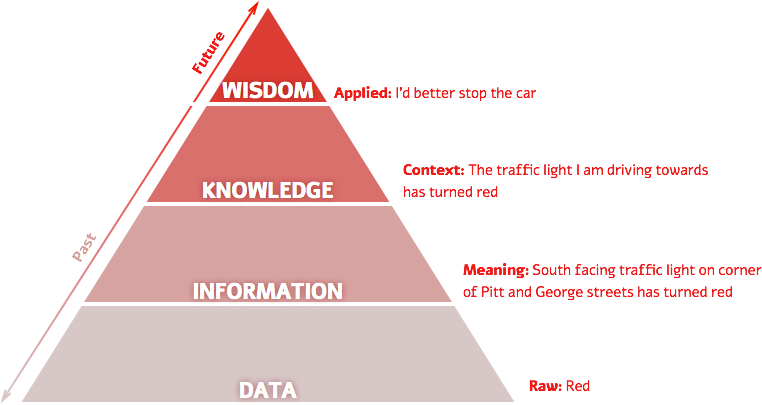

It is hard to find anyone in health care who does not believe that spending an extra $100 now on healthy behavior – exercise and proper nutrition, counseling for pre-diabetics, risk monitoring, and so on – could yield more than $120 in lowered costs and improved outcomes later. The numbers are fuzzy, of course, and there are plenty of methodological caveats, but there is little dispute about the plausibility and desirability of such an approach.

Yet neither individuals nor communities seem to act on the basis of this knowledge. Moreover, it’s likely that spending $110 now has no impact, as other factors dissipate any gain, but spending $110 million now (vs. a health-care budget of $100 million) should indeed return savings of $20 million annually over time. Individuals often lack willpower or access to healthy food or convenient exercise facilities, and are surrounded by poor examples that encourage instant gratification rather than effort and restraint. And, on a broader, institutional scale, the money spent and the money to be gained do not belong to the same pocket.

Enter HICCup!

The goal of HICCup, the Health Initiative* Coordinating Council, is to facilitate the launch of five to eight community-wide experiments dedicated to proving that this can work, and to learning from both successful and unsuccessful efforts. HICCup is a self-appointed counseling service and will persuade and guide local institutions to embrace a long-term perspective and launch a full-scale intervention experiment in their communities. For practical reasons, there are a few guidelines – but anyone who wants to do this without following our rules is welcome to do so. (*Yes, it used to be “health intervention…” but initiative is more friendly and positive, and still let us keep the logo!)

For starters, HICCup will focus on communities of 100,000 people or fewer. The majority of each community and its institutions must be enthusiastic for the initiative to gain traction. If the community members mostly work for just a few employers and obtain health care from just a few providers, that makes the effort of corralling the players easier. And, of course, you need community leaders – mayor, city council, and others – who will work together rather than undermine one another.

So, how will this be funded? Not by HICCup, which is only a coordinating body. The trick is for an investor in each community to capture some of what is being spent already on health care. As a rough calculation, assume $10,000 in annual per capita health-care costs, or $1 billion per year in a community of 100,000. (There are also all the separate costs of bad health, which are much harder to count or capture.) That money ultimately comes from individuals and employers who pay it in taxes, insurance premiums or direct payments; the place to intercept it is somewhere between the payers and the health-care delivery system.

Instead of spending $1 billion a year, imagine spending $1.1 billion the first two years, but, say, only $900 million in the fifth year (possibly a $300 million savings off projected costs of $1.2 billion by then). That sounds like an attractive proposition – but only if someone else will make that initial investment in return for a claim to those presumed later savings. These numbers are just for illustration; figuring out actual and predicted numbers for each community will be a key task.

The first challenge is for each HICCup community to get the involvement of a benevolent but ultimately profit-driven billionaire or hedge fund, or a philanthropic fund that sees a way to do good while earning money for future goodness. There are a lot of billionaires out there, some with vision. There are health-care companies that might bite, hedge funds looking for large-scale projects, and so-called social-impact bonds. There also are large employers that might decide to work with other employers in certain communities.

The funder makes a deal with whoever is responsible for the health-care costs (buyers): The funder makes upfront investment in health interventions and pays the health-care costs, against continued payment from the health-care buyers of the $1-billion yearly baseline, with the funder to keep (most of) the savings against originally predicted rising costs in later years. The money may be paid by employers, private insurers (which collect it from individuals, who, in the United States, are now required to buy insurance) or from government health-care funds, which will be the trickiest source.

One way or another, the investor/experiment manager will need to figure out how to realign some of the sick-care facilities and workers to some other role, including prevention, serving outsiders or some other use entirely. That’s the second challenge HICCup experimenters need to address – one that is being addressed in part by the creation of Accountable Care Organizations, but without community involvement in preventive health.

All together now!

All these entities will be taking a substantial leap of faith. But we believe they can succeed – especially if they work together through HICCup to figure out the numbers, study the effects of small-scale healthy-living/preventive health-care efforts, and encourage one another to move forward. Regardless, each investor must work with existing institutions – if only to get at the revenue stream initially and benefit from the lowered costs in later years.

Although grants are a nice source of funding for demonstration projects and research, the best way for HICCup’s vision to catch on and be widely copied is by adopting a for-profit approach that attracts broader investment once it is shown to work. Indeed, if a benefactor makes a donation, they feel good when they send off the money. An investor feels good only after the investment actually pays off.

Community officials and voluntary organizations also need to sign on…or they can drive the process and find the benefactor/investor. They will also contribute by implementing complementary changes in school meals and gym classes; enacting zoning and other changes to encourage cycling, walking, and the like; hiring health counselors and care workers; and perhaps working with local restaurants and food stores to subsidize healthy choices and discourage unhealthy ones. Local media can report on the experiment’s progress, and each community will likely engage in healthy rivalry with other HICCup experimenters.

Though it won’t get to keep the direct health-care cost savings, each community will get all the ancillary benefits of a healthy population, including an enhanced reputation. Indicators of population health include not just rates of obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, and diseases and related costs, but also whether the elderly can live (and be cared for) at home, absenteeism, school grades and graduation rates, employment statistics, accidents, and the like. Although the funder keeps the reduction in health-care costs, the community gets the benefit in the many payoffs from a healthier population over time.

Open enrollment

HICCup will not choose which communities participate. They will be choosing them selves. HICCup’s role will be to advise them and help them to communicate and learn from other communities going through the same process. We also want to be a clearinghouse for vendors of health-oriented tools, services, and programs. There are many bargains to be struck between communities and vendors offering discounts in exchange for wholesale adoption of their tools or programs.

However, there is one unbreakable rule: To work with HICCup, communities must collect and publish a lot of independently vetted data (without personal information, of course). For starters, they will need benchmarks of current conditions and projected costs, and then detailed statistics on the adoption of the measures, their impact and costs, and what happens over time. HICCup will welcome input from lawyers and actuaries!

It is now time to try this on a broad scale. Five years from now, we will wonder what took us so long to get started. So, again, who will those investors be?

Smartphone app visualises two similar running routesI am obsessed with my running app. Last week obsession became frustration verging on throw-the-phone-on-the-floor anger. Wednesday’s lunchtime 5km run was pretty good, almost back up to pre-Christmas pace. On Friday, I thought I had smashed it. The first 2km were very close to my perennial 5 min/km barrier. And I was pretty sure I had kept up the pace. But the app disagreed.As I ate my 347 calorie salad – simultaneously musing on how French dressing could make up 144 of them – I switched furiously between the two running route analyses. This was just preposterous; the GPS signal must have been confused; I must have been held up overtaking that tourist group for longer than I realised; or perhaps the app is just useless and all previous improvements in pace were bogus.My desire to count stuff is easy to poke fun at. It’s probably pretty unhealthy too. But it’s only going to be encouraged over the next few years. Wearable technology is here to stay. Smart phone cameras

Smartphone app visualises two similar running routesI am obsessed with my running app. Last week obsession became frustration verging on throw-the-phone-on-the-floor anger. Wednesday’s lunchtime 5km run was pretty good, almost back up to pre-Christmas pace. On Friday, I thought I had smashed it. The first 2km were very close to my perennial 5 min/km barrier. And I was pretty sure I had kept up the pace. But the app disagreed.As I ate my 347 calorie salad – simultaneously musing on how French dressing could make up 144 of them – I switched furiously between the two running route analyses. This was just preposterous; the GPS signal must have been confused; I must have been held up overtaking that tourist group for longer than I realised; or perhaps the app is just useless and all previous improvements in pace were bogus.My desire to count stuff is easy to poke fun at. It’s probably pretty unhealthy too. But it’s only going to be encouraged over the next few years. Wearable technology is here to stay. Smart phone cameras

Tony Stubblebine

Tony Stubblebine