http://swirlstats.com/students.html

http://swirlstats.com/students.html

Pretty cool… lots of good imagery for a presentation.

One day, it’ll find itself on the weather report.

Put another way, the weather report is one of the most popular, early uses of big data available in the community.

http://www.fastcoexist.com/3025365/find-out-when-youll-be-sick-with-the-first-online-flu-predictor

Want to know when exactly to start avoiding everyone around you who so much as sneezes? This online tool can tell you when the flu will strike in your city–more than two months in advance.

Luckily, it wasn’t the flu. But if it was, last week was also the first time I could have predicted when such a flu might strike my part of town, as it does during the peak flu months between October and April. That’s because, earlier this month, scientists at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health uploaded a first-of-its-kind flu prediction model online.

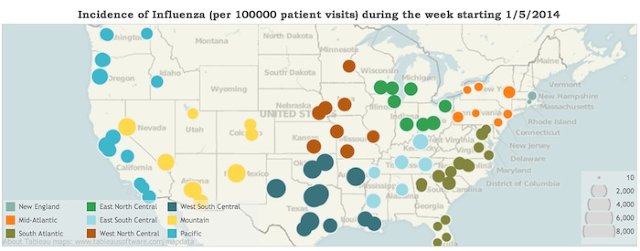

In December, assistant professor of environmental health sciences Jeffrey Shaman told Co.Exist about the tool he and his colleagues had developed to predict the flu up to nine weeks in advance. Using data from Google Flu Trends and weekly CDC infection rates, the Columbia model was able to predict the exact timing of flu arrival accurately in 63% of the American cities it analyzed.

One day, Shaman suggested, the predictions might become so accurate that they’re eventually broadcast next to the weather on TV.

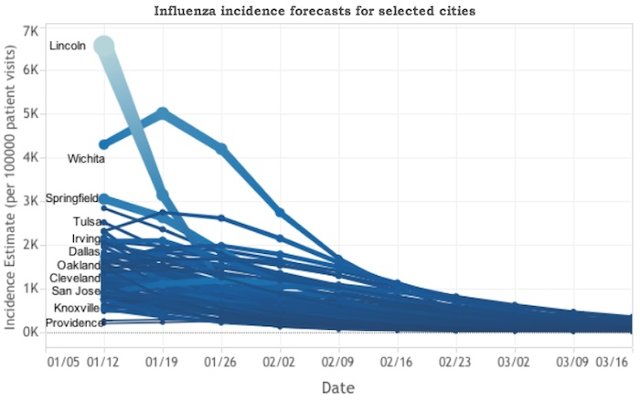

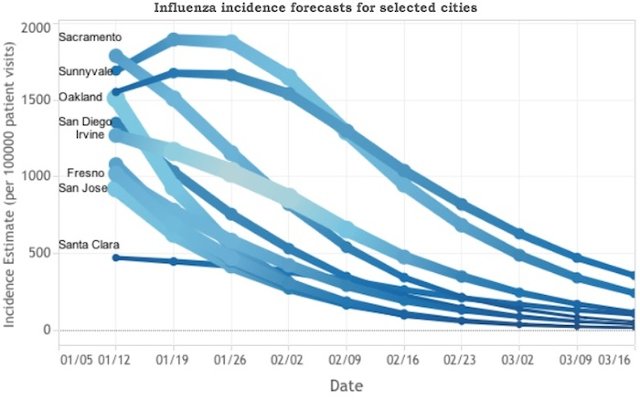

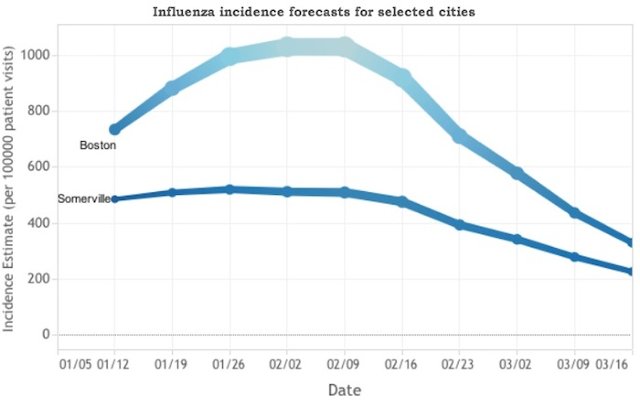

In the meantime, that model now exists on the good ‘ole Internet. It predicts some relief for Lincoln, Nebraska, which appears to be coming down from quite an illness, as does Wichita. Boston, on the other hand, looks like it’ll be experiencing an increase in flu cases over the next couple of weeks, as will New York City.

On the map above the predictor, you can check out CDC data for flu patient visits to the doctor’s office from the week prior. Next to the predictor, click on your state in the tree map to find out which cities will be most afflicted.

[Image: Blowing nose via Flickr user Anna Gutermuth]

http://www.iodine.com/blog/anti-smoking-ads/

If these images make you squirm or want to click away, you’re not alone.

How, then, can this type of message change the choices you make? Can we really be motivated by something that turns us off, rather than on?

You’d think, perhaps intuitively, that the scarier the ad, the more powerfully it affects our behavior. And the research supports that argument. Indeed, since the classic 1964 Surgeon General report on “Smoking and Health” came out 50 years ago this month, that’s been the basic strategy for health communication around the issue. But there’s a catch. A BIG one.

While we’ve seen a significant drop in global smoking rates (down 25% for men and 42% for women) since those landmark reports in the 1960s demonstrated the link between smoking and lung cancer, many people continue to smoke: 31% of men and 6% of women. In the U.S., 18% of adults (down by half since 1964) continue to do something they know might kill them.

Public health agencies have spent years communicating the dangers of smoking. Their anti-smoking ads have grown increasingly disturbing, threatening us with graphic images of bulging tumors and holes in our throats — possibly to try to reach that last stubborn segment of the population that hasn’t kicked the habit.

Turns out, the most recent and comprehensive research on so-called “fear appeals” and attitude change says that this kind of messaging does work, but only if the person watching the ad is confident that they are capable of making a change, such as quitting smoking. Public health gurus call this confidence in one’s ability to make a change “self-efficacy” — and threats only seem to work when efficacy is high. (The reverse is also true.)

If someone lacks efficacy, ads with fear appeals don’t help. In fact, they make the behaviorworse. How? Many people engage in unhealthy behavior because it makes them feel better and relieves their anxiety.

If you threaten someone who has little to no confidence they can change their behavior, their anxiety goes through the roof. What do they do? Perhaps turn off the threatening ad, walk away, and light up a cigarette — the very behavior you were trying to prevent. This same principle applies to other coping behaviors, such as eating unhealthy types of food or just too much of it.

Unfortunately, anxiety is quite common in this country. According to arecent Atlantic article, 1 in 4 Americans is likely to suffer from anxiety at some point in life. Making big life changes is tough, and it seems as though fear and anxiety don’t energize people, they just paralyze them.

A step in the right direction would be for ad campaigns to couple compelling threats with equally clear and specific paths to behavior change. Or why not apply the rewards built into reaching a new level in addictive video games to apps that people can use for real-life challenges? One great example of this is Superbetter, a social online game to help people build resilience and stay motivated while working to overcome injuries, anxiety, and depression.

Stand-alone threats implicitly assume that people don’t already know how bad their choices are, and can drive them to the very behaviors they wish they could change. Truly effective ad campaigns might still appeal to our fears, but they should also let us wash it all down with a confidence chaser that empowers the more anxious among us to act on our fears.

There’s a lot of good buried in this post, but it’s all starting to sounds like the development of a perfect map… not that inspiring.

The data is already there. At a national level, it can be used to inform a national increase in health funding… functioning like a CPI.

——-

Michael Porter defines value as “health outcomes achieved per dollar spent.” … An efficient business gets the most output possible, given current technology, from every dollar spent.

Porter and colleagues adapt microeconomics to health care through their definition of output: patient-centered health outcomes. These are results that individual patients desire: survival, speedy and uncomplicated recovery, and maintenance of well-being over the long term. These are also things that clinicians, payers, and purchasers should seek for their patients, employees, and customers.

The value movement’s definition of outcomes treats the patient as a whole person, insists that measures of outcome transcend disease-specific indicators to account for all of the patient’s conditions, and include data collected over time and space to produce comprehensive measures of patient well-being. Value proponents further insist that inputs be measured comprehensively to include all the costs of producing desired outcomes.

Widely adopted, the concept of value would provide a north star toward which health care providers could navigate. Its emphasis on the whole patient and comprehensively measured costs would encourage teamwork among clinicians and coordination of care across specialties, clinical units, and health care organizations. The focus on patient-centered outcomes would support increased effort to measure patient-reported outcomes of care, such as their level of function and perceived health status over time.

[…] the lack of data systems to support outcome measurement. Producing the holistic assessments needed requires the aggregation over time and space of data from multiple clinicians and health care organizations, as well as patients themselves. The health care system’s electronic data systems are just now entering the modern age.

To turn the promise of value measurement into the reality of better care at lower cost, a few short-term actions seem prudent. First, the nation needs a plan to turn the concept of value into practical indicators. Since government, the private sector, consumers and voters all have a vital stake in health system improvement, they should all participate in a process of perfecting and implementing value measures, preferably under the leadership of a respected, disinterested institution. The Institute of Medicine comes to mind, but others could be imagined. This process should produce an evolving set of measures that will be imperfect initially but improve over time.

Second, both government and the private sector need to invest in the science and electronic data systems that support value measurement. Investments in systems should focus on speeding the refinement of standards for defining and transporting critical data elements that must be shared by patients, providers, and insurers to create patient-centered outcome measures.

http://blogs.hbr.org/2013/09/getting-real-about-health-care-value/

via

by David Blumenthal and Kristof Stremikis | 12:15 PM September 17, 2013

Words can spearhead social transformation. Let’s hope that’s true for “value” in health care. Where other mantras – such as quality or managed care – have failed to galvanize the system’s diverse stakeholders, value may have a chance.

What seems special about the term is that, seemingly simple, it is actually complex and subtle. Under its umbrella, a wide range of interested parties can find the things they hold most dear, from improved patient outcomes to coordination of care to efficiency to patient-centeredness. And it is intuitively appealing. As Thomas Lee noted in the New England Journal of Medicine, “no one can oppose this goal and expect long-term success.”

The question, of course, is whether the term will help spur the fundamental changes that our health care sector so desperately needs. In this regard, a closer examination of the value concept confirms its appeal but also exposes the daunting challenges facing health system reformers.

Michael Porter has defined value as “health outcomes achieved per dollar spent.” Any survivor of introductory microeconomics will hear echoes in this phrase of one basic measure of economic efficiency: output per unit of input. An efficient business gets the most output possible, given current technology, from every dollar spent.

Porter and colleagues adapt microeconomics to health care through their definition of output: patient-centered health outcomes. These are results that individual patients desire: survival, speedy and uncomplicated recovery, and maintenance of well-being over the long term. These are also things that clinicians, payers, and purchasers should seek for their patients, employees, and customers. The value movement’s definition of outcomes treats the patient as a whole person, insists that measures of outcome transcend disease-specific indicators to account for all of the patient’s conditions, and include data collected over time and space to produce comprehensive measures of patient well-being. Value proponents further insist that inputs be measured comprehensively to include all the costs of producing desired outcomes.

Widely adopted, the concept of value would provide a north star toward which health care providers could navigate. Its emphasis on the whole patient and comprehensively measured costs would encourage teamwork among clinicians and coordination of care across specialties, clinical units, and health care organizations. The focus on patient-centered outcomes would support increased effort to measure patient-reported outcomes of care, such as their level of function and perceived health status over time.

Promising as it is, the emphasis on value also raises illuminating and challenging questions. The first is: why all the fuss with defining it? In most markets consumers define value by purchasing and using things. In the 1990s, personal computers had considerable value. We know that because consumers bought lots of them. Now, with the arrival of tablets, personal computers seem to be losing value. And so it goes for untold numbers of goods and services in our market-oriented economy. Eminent professors don’t wrack their brains defining the intrinsic value of electric shavers, overcoats, or roast beef.

We need to define the value of health care, however, for a simple but profound reason explained in 1963 by Nobel-prize-winning economist Kenneth Arrow. Arrow showed that health care markets don’t work as others do, because consumers lack the information to make good purchasing decisions. Health care is simply too complex for most people to understand. And health care decisions can be enormously consequential, with irreversible effects that make them qualitatively different from bad purchases in other markets. Americans are therefore reluctant to let the principle of caveat emptor prevail. One reason to define value carefully and systematically is to enable consumers to understand what they are getting, an essential condition for functioning health care markets.

The compelling need for a good definition of health care value highlights another fundamental challenge. We have not yet developed scientifically sound or accepted approaches to defining or measuring either patient-centered outcomes of care, or – surprisingly – the costs of producing those outcomes. The scientific hurdles to defining patient-centered outcomes are numerous. Outcomes can be subtle and multidimensional, involving not only physiological and functional results, but also patients’ perceptions and valuations of their care and health status. The ability of health care organizations to measure costs is primitive at best and doesn’t meet the standards used in many other advanced industries. Equally challenging is the lack of data systems to support outcome measurement. Producing the holistic assessments needed requires the aggregation over time and space of data from multiple clinicians and health care organizations, as well as patients themselves. The health care system’s electronic data systems are just now entering the modern age.

Given the value of measuring value, and the current obstacles to doing so, still another urgent question arises: what should we do now? Despite recent moderation in health care costs, our health care system is burning through the nation’s cash at an extraordinary rate and producing results that, by almost every currently available measure, are disappointing.

To turn the promise of value measurement into the reality of better care at lower cost, a few short-term actions seem prudent. First, the nation needs a plan to turn the concept of value into practical indicators. Since government, the private sector, consumers and voters all have a vital stake in health system improvement, they should all participate in a process of perfecting and implementing value measures, preferably under the leadership of a respected, disinterested institution. The Institute of Medicine comes to mind, but others could be imagined. This process should produce an evolving set of measures that will be imperfect initially but improve over time.

Second, both government and the private sector need to invest in the science and electronic data systems that support value measurement. Investments in systems should focus on speeding the refinement of standards for defining and transporting critical data elements that must be shared by patients, providers, and insurers to create patient-centered outcome measures.

Third, in consultation with consumers and providers, governments need to develop privacy and security policies that will assure consumers that their health care data will be protected when shared for the purpose of value measurement.

Last, and perhaps most important, the trend toward paying providers on the basis of the best available value measurements needs to continue. These payment policies motivate providers to use value measures to their fullest extent for the purpose of improving processes of care and meeting patients’ needs and expectation.

To some observers putting value at the forefront of health care reform may seem obvious and non-controversial. As Lee notes, who can be against it? To use an American cliché, it seems a little like motherhood and apple pie: comfortable and widely endorsed. But the value movement could be much more than that. When value does become a well-accepted principle, we’ll be much closer to making health care better for everyone.

Follow the Leading Health Care Innovation insight center on Twitter @HBRhealth. E-mail us athealtheditors@hbr.org, and sign up to receive updates here.

http://techcrunch.com/2014/01/15/vcs-investing-to-heal-u-s-healthcare/

VCs Investing To Heal U.S. Healthcare

The U.S. healthcare system is sick, but increasingly early stage investors are spending money on new technology companies they believe can help provide a cure.

The U.S. healthcare system is sick, but increasingly early stage investors are spending money on new technology companies they believe can help provide a cure.

Earlier this week, Greylock Partners, one of the investors behind Facebook and LinkedIn, and the Russian billionaire technology investor Yuri Milner put together a $1.2 million round alongside a group of co-investors to back First Opinion – a consumer facing service selling a way to text message doctors anytime of day or night.

Greylock and Milner join a growing roster of technology investors focused on healthcare in recent years. The number of companies raising money from investors for the first or second time has skyrocketed since the passage of the Affordable Care Act, according to data from CrunchBase.

In 2010, the year in which President Obama signed the ACA into law, there were only 17 seed- and Series A-stage healthcare-focused software and application development companies which had raised money from investors. By the end of last year, that number jumped to 89 companies tackling problems specifically related to the healthcare industry, according to CrunchBase metrics.

Across all categories, investors spent over $1.9 billion in 195 deals with commitments over $2 million, according to a report from early stage investment firm Rock Health. Funding was up 39% from 2012 and 119% from 2011, the Rock Health report said.

And there’s plenty of room for the market to grow, according to  Google Ventures’ general partner Dr. Krishna Yeshwant. “We’re still at the very beginning of what this is going to look like,” said Dr. Yeshwant.

Google Ventures’ general partner Dr. Krishna Yeshwant. “We’re still at the very beginning of what this is going to look like,” said Dr. Yeshwant.

Google Ventures is addressing the nation’s healthcare dilemma with investments in companies like the physicians’ office and network One Medical Group, which raised a later stage $30 million last March. At the opposite end of the spectrum in December 2013 Google invested in the $3 million seed financing of Doctor on Demand, which sells a service enabling users to video chat with doctors.

Unsurprisingly, the explosion in healthcare investments tracks directly back to the passage of the Affordable Care Act, investors said. “The incentives brought forward by the ACA shift what makes sense,” in healthcare, Dr. Yeshwant said.

“At the highest level there’s now a forcing function to take advantage of the efficiency technology provides,” said Bill Ericson, a general partner with Mohr Davidow Ventures, who led the firm’s investment in HealthTap, a service for consumers to message doctors with healthcare questions.

Overwhelmingly, Silicon Valley is leading the charge in these innovations, according to CrunchBase.

This flood of capital has pushed some investors like Founders Fund to re-think their strategy, and de-emphasize healthcare software in search of other, larger opportunities.

““The reason we have somewhat shifted focus away from healthcare IT is because there is so much investment going into that space. So we think the problems there are being sufficiently addressed by the full market.” said Brian Singerman, a partner at Founders Fund.

The firm’s most recent investment was in Oscar, a new, New York-based insurance company. Yes… an insurance company.

“In healthcare there is a tech stack around genomics, digitization, biometrics, analytics, and actual cures; one of the things that ties that all together is insurance,” said Singerman.

OK, so here’s the idea:

Our physical environment is loaded with cues capable of triggering healthy and unhealthy behaviours…

Rather than leaving it to fate, why not use a location-triggered message to steer away from temptation, and towards a healthy future.

The danger areas can be configured individually, crowd-sourced or pre-loaded, as can the messages.

http://www.theguardian.com/world/ng-interactive/2014/aviation-100-years

Kiln and the Guardian explored the 100-year history of passenger air travel, and to kick off the interactive is an interactive map that uses live flight data from FlightStats. The map shows all current flights in the air right now. Nice.

Be sure to click through all the tabs. They’re worth the watch and listen, with a combination of narration, interactive charts, and old photos.

And of course, if you like this, you’ll also enjoy Aaron Koblin’s classic Flight Patterns.

Gates Foundation backed Washington University team doing some amazing work on gathering, analysing and presenting global burden of disease metrics for easy browsing.

http://www.healthmetricsandevaluation.org/gbd/visualizations/gbd-arrow-diagram

IHME strives to make its data freely and easily accessible and to provide innovative ways to visualize complex topics. Our data visualizations allow you to see patterns and follow trends that are not readily apparent in the numbers themselves. Here you can watch how trends in mortality change over time, choose countries to compare progress in a variety of health areas, or see how countries compare against each other on a global map.

Not sure which visualization will provide you with the results you are looking for? Click here for a guide that will help you determine which tool will best address your data needs.

GBD Compare is new to IHME’s lineup of visualizations and has countless options for exploring health data. To help you navigate this new tool, we have a video tutorial that will orient you to its controls and show you how to interact with the data. You can also watch the video of IHME Director Christopher Murray presenting the tools for the first time at the public launch on March 5, 2013.

This interactive data visualization tool shows modeled trends in tobacco use and estimated cigarette consumption worldwide and by country for the years 1980 to 2012. Data were derived from nationally representative sources that measured tobacco use and reports on manufactured and nonmanufactured tobacco.

With this interactive map, you can explore health trends in the United States at the county level for both sexes in: life expectancy between 1985 and 2010, hypertension in 2001 and 2009, obesity from 2001 to 2011, and physical activity from 2001 to 2011.

Analyze the world’s health levels and trends in one interactive tool. Use treemaps, maps, and other charts to compare causes within a country, compare countries with regions or the world, and explore patterns and trends by country, age, and gender. Drill from a global view into specific details. Watch how disease patterns have changed over time. See which causes of death and disability are having more impact and which are waning.

How does input data become a GBD estimate? Walk through the estimation process for mortality trends for children and adults for 187 countries. See the source data and then watch as various stages in the estimation process reveal the final mortality estimates from 1970 to 1990.

Where do we have the best data on the different health conditions? For any age group, see where the various data sources have placed the trends in causes of death over time. You can examine more than 200 causes in both adjusted and pre-adjusted numbers, rates, and percentages for 187 countries.

What are the health challenges and successes in countries around the world?

How has the burden of different diseases, injuries, and risk factors moved up or down over time?

Where do we have the best data on the different health conditions?

What diseases and injuries cause the most death and disability globally?

The needle-less, sensor-laden transdermal patch is painless (I handled a prototype, which felt like sandpaper on the skin) and will soon be able to monitor everything you might find on a basic metabolic panel–a blood panel that measures glucose levels, kidney function, and electrolyte balance. Already, Sano’s prototype can measure glucose and potassium levels. There are enough probes on the wireless, battery-powered chip to continuously test up to a hundred different samples, and 30% to 40% of today’s blood diagnostics are compatible with the device.

Example of biomedical industry’s work on blood sensors

Apple is moving to expand its personnel working on wearable computers and medical-sensor-laden devices by hiring more scientists and specialists in the medical sensor field. Apple began work in earnest on a watch-like device late last decade, and it has worked with increasing efficiency and more dedicated resources on the project over the past couple of years. Last year, we published an extensive profile that indicated Apple has hired several scientists, engineers, and managers in the field of biomedical technologies, glucose sensors, and general fitness devices…

Smartening the iWatch team

Over the past couple of months, Apple has been seeking even more engineering prowess to work on products with medical sensors. Earlier this year, two notable people from the medical sensor world joined Apple to work on the team behind the iWatch’s hardware vision. Apple has hired away Nancy Dougherty from startup Sano Intelligence and Ravi Narasimhan from general medical devices firm Vital Connect. In her former job, Dougherty was in charge of hardware development. Narasimhan was the Vice President of Research and Development at his previous employer.

Unobtrusive blood reading

Sano Intelligence co-founders introducing their work (image)

Dougherty’s work at Sano Intelligence is incredibly interesting in light of Apple’s work on wearable devices, and it seems likely that she will bring this expertise from Sano over to Apple. While Sano Intelligence has yet to launch their product, it has been profiled by both The New York Times and Fast Company. The latter profile shares many details about the product: it is a small, painless patch that can work on the arm and uses needle-less technologies to read and analyze a user’s blood.

The needle-less, sensor-laden transdermal patch is painless (I handled a prototype, which felt like sandpaper on the skin) and will soon be able to monitor everything you might find on a basic metabolic panel–a blood panel that measures glucose levels, kidney function, and electrolyte balance. Already, Sano’s prototype can measure glucose and potassium levels. There are enough probes on the wireless, battery-powered chip to continuously test up to a hundred different samples, and 30% to 40% of today’s blood diagnostics are compatible with the device.

With the technology for reading blood able to be integrated into a small patch, it seems plausible that Apple is working to integrate such a technology into its so-called “iWatch.” For a diabetic or any other user wanting to monitor their blood, this type of innovation would likely be considered incredible. More so if it is integrated into a mass-produced product with the Apple brand. Just like Apple popularized music players and tablets, it could take medical sensor technology and health monitoring to mainstream levels.

Earlier this week, Google entered the picture of future medical devices by announcing its development of eye contact lenses that could analyze glucose levels via a person’s tears. This technology is seemingly far from store shelves as keeping the hardware in an eye likely poses several regulatory concerns. By putting similar technology on a wrist or an arm, perhaps Apple will be able to beat Google to market with this potentially life-changing medical technology.

While the aforementioned work by Dougherty occurred at Sano Intelligence, the fact that she “solely” developed this hardware means that her move to Apple is a remarkable poaching for the iPhone maker and a significant loss for a small, stealth startup. She notes her involvement at Sano on her LinkedIn profile (which also confirms her new job at Apple):

– Hardware Lead in a very early stage company designing a novel system to continuously monitor blood chemistry via microneedles in the interstitial fluid. Brought system from conception through development and board spins to a functioning wearable pilot device.

– Solely responsible for electrical design, testing, and bring-up as well as system integration; managing contractors for layout, assembly, and mechanical systems

– Building laboratory data collection systems and other required electrical and mechanical systems to support chemical development

Dougherty’s work at Sano Intelligence was not her first trip in the medical sensor development field. Before joining that company, she worked on “research and development for an FDA regulated Class I medical device; a Bluetooth-enabled electronic “Band-Aid” that monitors heart rate, respiration, motion, and temperature” for another digital health company, according to her publicly available resume.

Patent portfolio

At Vital Connect, Narasimhan was a research and development-focused vice president. As Vital Connect is a large company, it is unclear how responsible Narasimhan actually was for the hardware development, but it is clear that he has expertise in managing teams responsible for biosensors. Their sensor can be worn on the skin (usually around the chest area) and is able to monitor several different pieces of data. As can be seen in the description from Vital Connect (above), their technology can measure steps, skin temperature, respiratory rate, and can even detect falls. These data points would be significant compliments to a wearable computer that is already analyzing blood data.

Besides his management role at Vital Connect, Narasimhan comes to Apple with over “40 patents granted and over 15 pending,” according to his LinkedIn profile. Many of these patents are in the medical sensor realm, and this demonstrates how his expertise could assist Apple in its work on wearable devices. Narasimhan has patents for measuring the respiratory rate of a user, and, interestingly, the measurement of a person’s body in space to tell if they have fallen. The latter technology in a mass-produced device would likely improve the quality of life for the elderly or others prone to falling.

Of course, it is not certain that the work of either Narasimhan or Dougherty will directly appear in an Apple wearable computer or other device. What this information does indicate, however, is that Apple is growing its team of medical sensor specialists by hiring some of the world’s most forward-thinking experts in seamless mobile medical technologies.

Silicon Valley

Apple is not the only company boosting its resources for utilities that can measure blood. According to sources, other major Silicon Valley companies are racing Apple to hire the world’s top experts in blood monitoring through skin.

Other biometric technologies

In addition to focusing on sensors that could monitor a person’s activity, motion, and blood through the skin, sources say that Apple is actively working on other biometric technologies. As we reported in 2013, Apple is actively working on embedding fingerprint scanners into Multi-Touch screens. It seems plausible that in a few years down the roadmap, Apple’s Touch ID fingerprint scanners could be integrated into the iPhone or iPad screen, not into the Home button.

Perhaps more interesting, Apple is also actively investigating iris scanning technology, according to sources. This information comes as a Samsung executive confirmed that Samsung is developing iris scanning technologies for upcoming smartphones. It is currently unknown if iris scanning to unlock a phone will arrive with the Galaxy S5 this year.

Apple is also said to be studying new ways of applying sensors such as compasses and accelerometers to improve facial recognition. These technologies could be instrumental in improving security, photography, and other existing facets of Apple’s mobile devices. It does not immediately seem intuitive to have new facial and iris recognition technologies on wearable devices, so it is unlikely that those technologies will make the cut for the future “iWatch.”

Big plans

While 2013 focused on improvements to Apple’s existing software and hardware platforms, Apple CEO Tim Cook has teased that 2014 will include even bigger plans. “We have a lot to look forward to in 2014, including some big plans that we think customers are going to love,” Cook told employees in December of 2013. These plans likely include larger-screened iPhones and iPads, updates to iOS and OS X, and sources are adamant that Apple will revamp its television strategy this year. But is an iWatch in the cards of 2014? Only time will tell. Regardless of when the product is planned for launch, it appears that Apple is stacking up its resources to create a wearable computer that is truly groundbreaking for the medical world, and that the company will not introduce it until it is ready.

https://lift.do/quantified-diet

The Quantified Diet Project aims for two things:

#1. Help one million people make a healthy diet change leading to: weight loss, overall health, and/or more energy. We’re providing 10 popular diets with expert advice.

#2. Perform the largest-ever measurement of popular diets. What works? How do popular diets compare? How can we all be more successful? We’re working with UC Berkeley on the science and the analysis.

The official launch is January 1st, but you can start contributing to our science right now by filling out this survey.

You’ll follow one of the following diets for four weeks:

During the diet, you’ll use the Lift app to receive daily prompts and to track your progress.

When you need help, you’ll have access to our hand-picked experts and to tips from the rest of the community.

Science aside, the first goal is for you to make a healthy diet change. This is our specialty.

Also, there will be prizes available at important milestones.

In order to do this in a scientific way we’re working with nutritionists and statisticians from UC Berkeley.

During the sign-up process, you’ll have the option to be given a diet that we’ve selected for you. The scientific process calls this part of the experiment randomization. The intent is to remove bias—perhaps fans of the4-Hour Body diet are inherently more motivated than fans of the USDA.

I was skeptical about people accepting our diet recommendation for them, but early joiners have voted 3 to 4 to participate in the randomized trial. (There will also be an opt-out of the randomization step, for those 1 in 4 people who want complete control.)

After we get you going on your new diet, we’ll measure via Lift and occasional surveys:

Of course, we’re going to be careful to respect your privacy. All data will be aggregated and anonymized. That’s really important to us.

You know what else is important? Your feedback. Email me or comment right here. I’m tony@lift.do.