Monthly Archives: December 2013

Big Data supporting NZ diabetes policy

- NZ is using big data to drive improvements in diabetes policy and planning

- The Virtual Diabetes Register (VDR) is aggregating data from 6 data sources:

- hospital admissions coded for diabetes

- outpatient attendees for diabetes

- diabetes retinal screening

- prescriptions of specific antidiabetic therapies

- laboratory orders for measuring diabetes management

- primary health (general practitioner) enrollments

- the analytics showed that Indian and Pacific people have the highest diabetes prevalence rates

http://www.futuregov.asia/articles/2013/dec/13/new-zealand-health-improves-diabetes-policy-big-da/

NEW ZEALAND HEALTH IMPROVES DIABETES POLICY WITH BIG DATA ANALYTICS

By Kelly Ng | 13 December 2013 | Views: 2743

The Ministry of Health New Zealand uses big data analytics to accurately determine current and predict future diabetic population to improve diabetes policy planning.

In collaboration with experts from the New Zealand Society for the Study of Diabetes (NZSSD), the ministry created a Virtual Diabetes Register (VDR) that pulls and filters health data from six major databases.

The six data sources were: hospital admissions coded for diabetes, outpatient attendees for diabetes and diabetes retinal screening, prescriptions of specific antidiabetic therapies, laboratory orders for measuring diabetes management and primary health (general practitioner) enrollments.

According to Emmanuel Jo, Principal Technical Specialist at Health Workforce New Zealand, Ministry of Health, the previous way of measuring diabetes using national surveys was inefficient, expensive and had a high error rate.

The new analytical model, using SAS software, significantly improved the accuracy and robustness of the system, combining several data sources to generate greater insights.

Interestingly, analytics showed that Indian and Pacific people have the highest diabetes prevalence rate, said Dr. Paul Drury, Clinical Director of the Diabetes Auckland Centre and Medical Director of NZSSD. Health policies can therefore be focused on this group.

“We have 20 different District Health Boards, and the data can show them how many diabetic people are in their area,” Drury said.

“GPs should know already how many they have, but the VDR is also able to help them predict who may be at risk so they can be prepared. By knowing the populations where diabetes is more prevalent, more resources can be directed at them to provide clinical quality improvements,” he added

Patient privacy is protected by regulating access to data in the VDR.

Simply Statistics on scientific folly…

A summary of the evidence that most published research is false

One of the hottest topics in science has two main conclusions:

- Most published research is false

- There is a reproducibility crisis in science

The first claim is often stated in a slightly different way: that most results of scientific experiments do not replicate. I recently got caught up in this debate and I frequently get asked about it.

So I thought I’d do a very brief review of the reported evidence for the two perceived crises. An important point is all of the scientists below have made the best effort they can to tackle a fairly complicated problem and this is early days in the study of science-wise false discovery rates. But the take home message is that there is currently no definitive evidence one way or another about whether most results are false.

- Paper: Why most published research findings are false. Main idea: People use hypothesis testing to determine if specific scientific discoveries are significant. This significance calculation is used as a screening mechanism in the scientific literature. Under assumptions about the way people perform these tests and report them it is possible to construct a universe where most published findings are false positive results. Important drawback: The paper contains no real data, it is purely based on conjecture and simulation.

- Paper: Drug development: Raise standards for preclinical research. Main idea: Many drugs fail when they move through the development process. Amgen scientists tried to replicate 53 high-profile basic research findings in cancer and could only replicate 6. Important drawback: This is not a scientific paper. The study design, replication attempts, selected studies, and the statistical methods to define “replicate” are not defined. No data is available or provided.

- Paper: An estimate of the science-wise false discovery rate and application to the top medical literature. Main idea: The paper collects P-values from published abstracts of papers in the medical literature and uses a statistical method to estimate the false discovery rate proposed in paper 1 above. Important drawback: The paper only collected data from major medical journals and the abstracts. P-values can be manipulated in many ways that could call into question the statistical results in the paper.

- Paper: Revised standards for statistical evidence. Main idea: The P-value cutoff of 0.05 is used by many journals to determine statistical significance. This paper proposes an alternative method for screening hypotheses based on Bayes factors. Important drawback: The paper is a theoretical and philosophical argument for simple hypothesis tests. The data analysis recalculates Bayes factors for reported t-statistics and plots the Bayes factor versus the t-test then makes an argument for why one is better than the other.

- Paper: Contradicted and initially stronger effects in highly cited research Main idea: This paper looks at studies that attempted to answer the same scientific question where the second study had a larger sample size or more robust (e.g. randomized trial) study design. Some effects reported in the second study do not match the results exactly from the first. Important drawback: The title does not match the results. 16% of studies were contradicted (meaning effect in a different direction). 16% reported smaller effect size, 44% were replicated and 24% were unchallenged. So 44% + 24% + 16% = 86% were not contradicted. Lack of replication is also not proof of error.

- Paper: Modeling the effects of subjective and objective decision making in scientific peer review. Main idea: This paper considers a theoretical model for how referees of scientific papers may behave socially. They use simulations to point out how an effect called “herding” (basically peer-mimicking) may lead to biases in the review process. Important drawback: The model makes major simplifying assumptions about human behavior and supports these conclusions entirely with simulation. No data is presented.

- Paper: Repeatability of published microarray gene expression analyses. Main idea: This paper attempts to collect the data used in published papers and to repeat one randomly selected analysis from the paper. For many of the papers the data was either not available or available in a format that made it difficult/impossible to repeat the analysis performed in the original paper. The types of software used were also not clear. Important drawback: This paper was written about 18 data sets in 2005-2006. This is both early in the era of reproducibility and not comprehensive in any way. This says nothing about the rate of false discoveries in the medical literature but does speak to the reproducibility of genomics experiments 10 years ago.

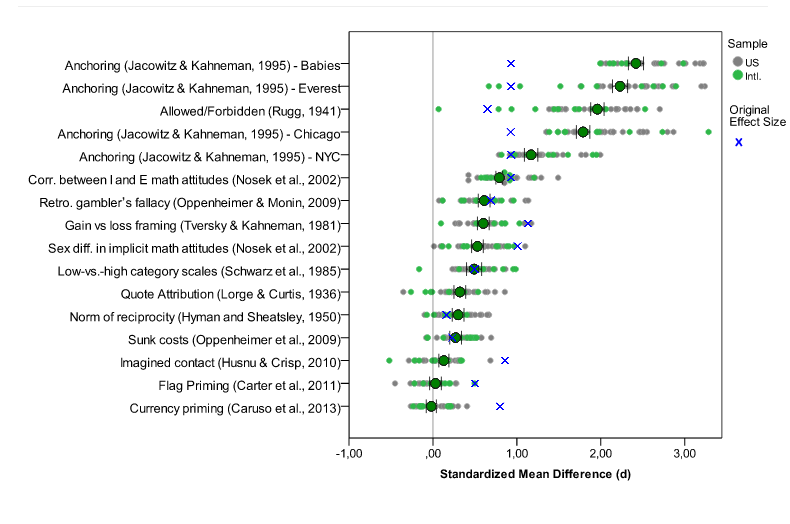

- Paper: Investigating variation in replicability: The “Many Labs” replication project. (not yet published) Main idea: The idea is to take a bunch of published high-profile results and try to get multiple labs to replicate the results. They successfully replicated 10 out of 13 results and the distribution of results you see is about what you’d expect (see embedded figure below). Important drawback: The paper isn’t published yet and it only covers 13 experiments. That being said, this is by far the strongest, most comprehensive, and most reproducible analysis of replication among all the papers surveyed here.

I do think that the reviewed papers are important contributions because they draw attention to real concerns about the modern scientific process. Namely

- We need more statistical literacy

- We need more computational literacy

- We need to require code be published

- We need mechanisms of peer review that deal with code

- We need a culture that doesn’t use reproducibility as a weapon

- We need increased transparency in review and evaluation of papers

Some of these have simple fixes (more statistics courses, publishing code) some are much, much harder (changing publication/review culture).

The Many Labs project (Paper 8) points out that statistical research is proceeding in a fairly reasonable fashion. Some effects are overestimated in individual studies, some are underestimated, and some are just about right. Regardless, no single study should stand alone as the last word about an important scientific issue. It obviously won’t be possible to replicate every study as intensely as those in the Many Labs project, but this is a reassuring piece of evidence that things aren’t as bad as some paper titles and headlines may make it seem.

Many labs data. Blue x’s are original effect sizes. Other dots are effect sizes from replication experiments (http://rolfzwaan.blogspot.com/2013/11/what-can-we-learn-from-many-labs.html)

Many labs data. Blue x’s are original effect sizes. Other dots are effect sizes from replication experiments (http://rolfzwaan.blogspot.com/2013/11/what-can-we-learn-from-many-labs.html)

The Many Labs results suggest that the hype about the failures of science are, at the very least, premature. I think an equally important idea is that science has pretty much always worked with some number of false positive and irreplicable studies. This was beautifully described by Jared Horvath in this blog post from the Economist. I think the take home message is that regardless of the rate of false discoveries, the scientific process has led to amazing and life-altering discoveries.

The universe is not made of atoms. It’s made of TINY STORIES.

Zeitgebers

Zeitgerbers: Outside time cues that make fine adjustments which mimic the changes in light and dark that take place throughout the year.

SNOOZERS ARE, IN FACT, LOSERS

On a typical workday morning, if you’re like most people, you don’t wake up naturally. Instead, the ring of an alarm clock probably jerks you out of sleep. Depending on when you went to bed, what day of the week it is, and how deeply you were sleeping, you may not understand where you are, or why there’s an infernal chiming sound. Then you throw out your arm and hit the snooze button, silencing the noise for at least a few moments. Just another couple of minutes, you think. Then maybe a few minutes more.

It may seem like you’re giving yourself a few extra minutes to collect your thoughts. But what you’re actually doing is making the wake-up process more difficult and drawn out. If you manage to drift off again, you are likely plunging your brain back into the beginning of the sleep cycle, which is the worst point to be woken up—and the harder we feel it is for us to wake up, the worse we think we’ve slept. (Ian Parker wrote about the development of a new drug for insomnia in the magazine last week.)

One of the consequences of waking up suddenly, and too early, is a phenomenon called sleep inertia. First given a name in 1976, sleep inertia refers to that period between waking and being fully awake when you feel groggy. The more abruptly you are awakened, the more severe the sleep inertia. While we may feel that we wake up quickly enough, transitioning easily between sleep mode and awake mode, the process is in reality far more gradual. Our brain-stem arousal systems (the parts of the brain responsible for basic physiological functioning) are activated almost instantly. But our cortical regions, especially the prefrontal cortex (the part of the brain involved in decision-making and self-control), take longer to come on board.

In those early waking minutes, our memory, reaction time, ability to perform basic mathematical tasks, and alertness and attention all suffer. Even simple tasks, like finding and turning on the light switch, become far more complicated. As a result, our decisions are neither rational nor optimal. In fact, according to Kenneth Wright, a neuroscientist and chronobiology expert, “Cognition is best several hours prior to habitual sleep time, and worst near habitual wake time.” In the grip of sleep inertia, we may well do something we know we shouldn’t. Whether or not to hit the snooze button is just about the first decision we make. Little wonder that it’s not always the optimal one.

Other research has found that sleep inertia can last two hours or longer. In one study that monitored people for three days in a row, the sleep researchers Charles Czeisler and Megan Jewett and their colleagues at Harvard Medical School found that sleep inertia took anywhere from two to four hours to disappear completely. While the participants said they felt awake after two-thirds of an hour, their cognitive faculties didn’t entirely catch up for several hours. Eating breakfast, showering, or turning on all the lights for maximum morning brightness didn’t mitigate the results. No matter what, our brains take far longer than we might expect to get up to speed.

When we do wake up naturally, as on a relaxed weekend morning, we do so based mainly on two factors: the amount of external light and the setting of our internal alarm clock—our circadian rhythm. The internal clock isn’t perfectly correlated with the external one, and so every day, we use outside time cues, called zeitgebers, to make fine adjustments that mimic the changes in light and dark that take place throughout the year.

The difference between one’s actual, socially mandated wake-up time and one’s natural, biologically optimal wake-up time is something that Till Roenneberg, a professor of chronobiology at Ludwig-Maximilians University in Munich, calls “social jetlag.” It’s a measurement not of sleep duration but of sleep timing: Are we sleeping in the windows of time that are best for our bodies? According to Roenneberg’s most recent estimates, based on a database of more than sixty-five thousand people, approximately a third of the population suffers from extreme social jetlag—an average difference of over two hours between their natural waking time and their socially obligated one. Sixty-nine per cent suffer from a milder form, of at least one hour.

Roenneberg and the psychologist Marc Wittmann have found that the chronic mismatch between biological and social sleep time comes at a high cost: alcohol, cigarette, and caffeine use increase—and each hour of social jetlag correlates with a roughly thirty-three per cent greater chance of obesity. “The practice of going to sleep and waking up at ‘unnatural’ times,” Roenneberg says, “could be the most prevalent high-risk behaviour in modern society.” According to Roenneberg, poor sleep timing stresses our system so much that it is one of the reasons that night-shift workers often suffer higher-than-normal rates of cancer, potentially fatal heart conditions, andother chronic disease, like metabolic syndrome and diabetes. Another study, published earlier this year and focussing on medical-school performance, found that sleep timing, more than length or quality, affected how well students performed in class and on their preclinical board exams. It didn’t really matter how long they had slept or whether they saw themselves as morning people or not; what made a difference was when they actually went to bed—and when they woke up. It’s bad to sleep too little; it’s also bad, and maybe even worse, to wake up when it’s dark.

Fortunately, the effects of sleep inertia and social jetlag seem to be reversible. When Wrightasked a group of young adults to embark on a weeklong camping trip, he discovered a striking pattern: before the week was out, the negative sleep patterns that he’d previously observed disappeared. In the days leading up to the trip, he had noted that the subjects’ bodies would begin releasing the sleep hormone melatonin about two hours prior to sleep, around 10:30 P.M.A decrease in the hormone, on the other hand, took place after wake-up, around 8 A.M. After the camping trip, those patterns had changed significantly. Now the melatonin levels increased around sunset—and decreased just after sunrise, an average of fifty minutes before wake-up time. In other words, not only did the time outside, in the absence of artificial light and alarm clocks, make it easier for people to fall asleep, it made it easier for them to wake up: the subjects’ sleep rhythms would start preparing for wake-up just after sunrise, so that by the time they got up, they were far more awake than they would have otherwise been. The sleep inertia was largely gone.

Wright concluded that much of our early morning grogginess is a result of displaced melatonin—of the fact that, under current social-jetlag conditions, the hormone typically dissipates two hours after waking, as opposed to while we’re still asleep. If we could just synchronize our sleep more closely with natural light patterns, it would become far easier to wake up. It wouldn’t be unprecedented. In the early nineteenth century, the United States had a hundred and forty-four separate time zones. Cities set their own local time, typically so that noon would correspond to the moment the sun reached its apex in the sky; when it was noon in Manhattan, it was five till in Philadelphia. But on November 18, 1883, the country settled on four standard time zones; railroads and interstate commerce had made the prior arrangement impractical. By 1884, the entire globe would be divided into twenty-four time zones. Reverting to hyperlocal time zones might seem like it could lead to a terrible loss of productivity. But who knows what could happen if people started work without a two-hour lag, during which their cognitive abilities are only shadows of their full selves?

Theodore Roethke had the right idea when he wrote his famous line “I wake to sleep, and take my waking slow.” We do wake to a sleep of sorts: a state of not-quite-alertness, more akin to a sleepwalker’s unconscious autopilot than the vigilance and care we’d most like to associate with our own thinking. And taking our waking slow, without the jar of an alarm and with the rhythms of light and biology, may be our best defense against the thoughtlessness of a sleep-addled brain, a way to insure that, when we do wake fully, we are making the most of what our minds have to offer.

Maria Konnikova is the author of “Mastermind: How to Think Like Sherlock Holmes.”

Photograph: Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone/Getty.

BMJ: Exercise just as good as drugs in war on major disease

- BMJ article highlights relative effectiveness of exercise vs drugs for common conditions

- Only drug/condition combo that was better than exercise was heart failure/diuretics

Exercise just as good as drugs in war on major disease

Photo: Alamy

1:00PM GMT 13 Dec 2013

A study of more than 300 trials has found that physical activity was better than medication in helping patients recovering from strokes – and just as good as drugs in protecting against diabetes and in stopping heart disease worsening.

The research, published in the British Medical Journal, analysed data about studies on 340,000 patients diagnosed with one of four diseases: heart disease, chronic heart failure, stroke or diabetes.

Researchers said the findings suggested that regular exercise could be “quite potent” in improving survival chances, but said that until more studies are done, patients should not stop taking their tablets without taking medical advice.

The landmark research compared the mortality rates of those prescribed medication for common serious health conditions, with those who were instead enrolled on exercise programmes.

The research found that while medication worked best for those who had suffered heart failure, in all the other groups of patients, exercise was at least as effective as the drugs which are normally prescribed.

People with heart disease who exercised but did not use commonly prescribed medications, including statins, and drugs given to reduce blood clots had the same risk of dying as patients taking the medication.

Similarly, people with borderline diabetes who exercised had the same survival chances as those taking the most commonly prescribed drugs.

Drugs compared with exercise included statins, which are given to around five million patients suffering from heart disease, or an increased risk of the condition.

The study was carried out by researcher Huseyin Naci of LSE Health, London School of Economics and Political Science and Harvard Medical School, with US colleagues at Stanford University School of Medicine.

He said prescription drug rates are soaring but activity levels are falling, with only 14 per cent of British adults exercising regularly.

In 2010 an average of 17.7 prescriptions was issued for every person in England, compared with 11.2 in 2000.

Mr Naci said: “Exercise should be considered as a viable alternative to, or alongside, drug therapy.”

Dr John Ioannidis, the director of the Stanford Prevention Research Center at the Stanford University School of Medicine, said: “Our results suggest that exercise can be quite potent.”

Other medications compared with exercise included blood-clotting medicines given to patients recovering from stroke, and alpha-glucosidase inhibitors given to patients on the cusp of developing diabetes.

Only the patients who were recovering from heart failure fared best when prescribed drugs, where anti-diuretic medication was most effective.

However, they said their analysis found far more trials examining drugs, than those which measured the impact of exercise.

They said there was a need for more research into the benefits of exercise for those suffering from serious health problems.

Researchers stressed that they were not suggesting that anyone should stop taking medications they had been prescribed, but suggested patients should think “long and hard” about their lifestyles, and talk to their doctors about incorporating more exercise into their daily routines.

Sir Muir Gray – ACSQHC Presentation

- We’re entering a new era in the NHS where there is “NO MORE MONEY“

@19min: describes “three big businesses in respiratory disease – asthma, COPD, apnoea”

- Value = Outcomes / Costs

- Outcome = Effectiveness (EBM+Quality) – Harm (Safety)

- Costs = Money + Time + Carbon

@22mins: moving from guideline care to personalised care

@26mins: Bureaucracy is important and necessary, but should stick to what it’s good at doing:

- The fair and open employment and promotion of people

- The un-corrupt management of money

- !! Not the curing of disease or delivery of health care – populations defined by need, not jurisdiction

@32mins: law of diminishing returns – benefits plateau as invested resources rise

@33mins: Harmful effects of healthcare increase in direct proportion to the resources invested

@34mins: combine the 2 curves – get a j-shaped curve with a point of optimality – the point of investment after which, the health gain may start to decline

@35mins: as the rate of intervention in the population increases, the balance of benefit and harm also changes for the individual patient

@37mins: value spectrum

[HIGH VALUE]

– necessary

– appropriate

[LOW VALUE]

– inappropriate

– futile

[NEGATIVE VALUE]

@39mins: The Payers’ Archipelago

20th Century Care >> 21st Century Care

Doctor >> Patient

Bureaucracy >> Network

Institutions >> Systems

@42mins: clinicians responsible for whole populations, not just the patients in front of them

@45mins: How to start a revolution

– change the culture – destabilise and constrain; control language

– engage patients and citizens, and the future leaders of 2033

– structure doesn’t matter (5%)

– systems (40%)

– culture or mindset (50%)

@46mins: Culture – the shared tacit assumptions of a group that it has learned in coping with external threats and dealing with internal relationships” Schein (1999) The Corporate Culture Survival Guide

@47mins50s: data doesn’t change the world, emotion changes the world

– atlases written for OMG effect

– programme budgeting

destabilise then constrain then change the language

@49mins: MUDA means waste — resource consumption that doesn’t contribute to the outcome. motonai – the feeling of regret that resources are being wasted. ban old language.

@51mins: mandatory training in new thinking

The Third Healthcare Revolution is already underway

1. PHONE

2. CITIZENS

3. KNOWLEDGE

The third healthcare revolution will come out of the barrel of a smartphone

@56mins: Healthcare is too complex to be run by bureaucracies or markets. Work like an ant colony – neither markets nor bureaucracies can solve the challenges of complexity.

PDF: Sir-Muir-Gray-Masterclass-presentation-1-Oct-2013

ASQHC Presentation link: http://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/medical-practice-variation/presentations/

Forcing the prevention industry – a 10 year journey

Vision

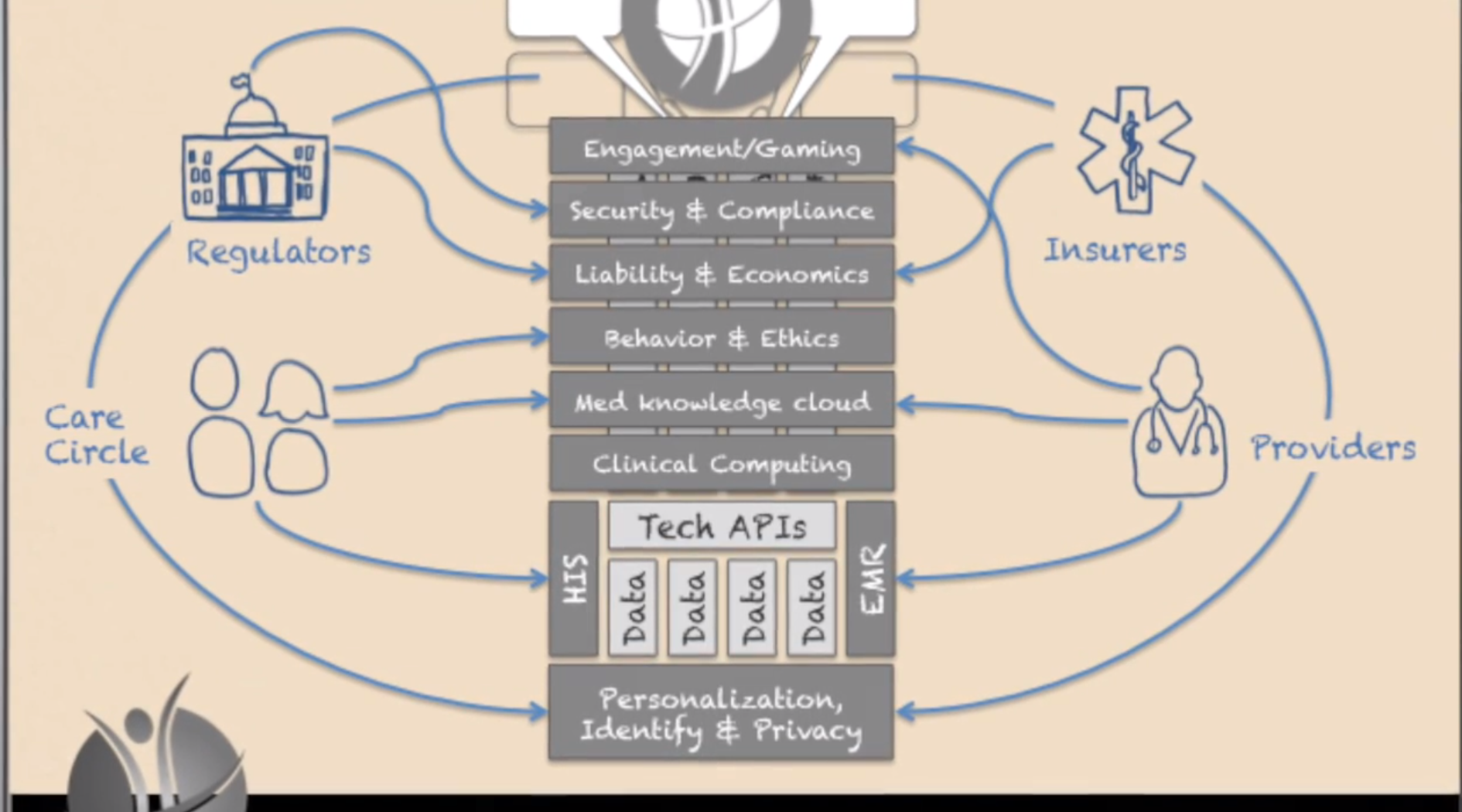

- The Future of Human API www.thehumanapi.com

- Forcing the prevention industry into existence

- Stage Zero disease detection and treatment

Critical trends:

- lab-in-a-box diagnostics

- quantified self

- medical printing

When these trends converge, there’ll be an inflection point where a market is established.

Health data moves from system of record >> system of engagement.

Promoting the evolution from a Product mentality to a Market mentality

As treatment starts to focus on Stage Zero/pre-clinical disease, it turns into prevention.

Video: http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=gJHaoqeucX8

The Asymptotic Shift From Disease To Prevention–Thoughts For Digital Health

I’ve stolen from two great thinkers, so let’s get that out of the way. The first isDaniel Kraft, MD. Daniel Kraft is a Stanford and Harvard trained physician-scientist, inventor, entrepreneur, and innovator. He’s the founded and Executive Director of FutureMed, a program that explores convergent, rapidly developing technologies and their potential in biomedicine and healthcare. He’s also a go-to source on digital health. I’m stealing “zero stage disease” from Dr. Kraft. Simply put, it’s the concept of disease at its most early, sub-clinical stage. It’s a point where interventions can halt or change a process and potentially eliminate any significant manifestation of disease.

The second source of inspiration is Richie Etwaru. He is a brilliant and compelling speaker and a champion for global innovation, Mr. Etwaru, is responsible for defining and delivering the global next generation enterprise product suite for health and life sciences at Cegedim RelationshipManagement. His inspiring video, The Future of Human API really got me thinking.

At the heart of Mr. Etwaru’s discussion is the emergence of prevention–not treatment–as the “next big thing”.

Ok, nothing new so far. But the important changes seen in the digital health movement have given us a profound opportunity to move away from the conventional clinical identification of a that golf-ball sized tumor in your chest to a much more sophisticated and subtle observation. We are beginning to find a new disease stage–different from the numbers and letters seen in cancer staging. The disease stage is getting closer and closer to zero. It’s taking an asymptotic path that connects disease with prevention. The point here is that the holy grail of prevention isn’t born of health and wellness. Prevention is born out of disease and our new-found ability to find it by looking closer and earlier. Think quantified self and Google Calico.

And here lies the magic.

We all live in the era of disease. And the vast majority of healthcare costs are spent after something happens. The simple reality is that prevention is difficult to fund and the health-economic model is so skewed to sickness and the end of life that it’s almost impossible to change. But if we can treat illness earlier and earlier–the concept of an asymptote–we build a model where prevention and disease share the very same border. They become, in essence, the same. And it’s here that early, early, early disease stage recognition (Stage Zero) becomes prevention. The combination of passive (sensor mediated) observation and proactive life-style strategies for disease suppression can define a new era of health and wellness.

Keep Critical! Follow me on Twitter and stay healthy!

NeuroOn sleep tracking mask…

Polyphasic sleep looks like something I want to get into, though am not convinced this is the way to achieve it. Will see how the trials go….

http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/intelclinic/neuroon-worlds-first-sleep-mask-for-polyphasic-sle

The NeuroOn is for you!

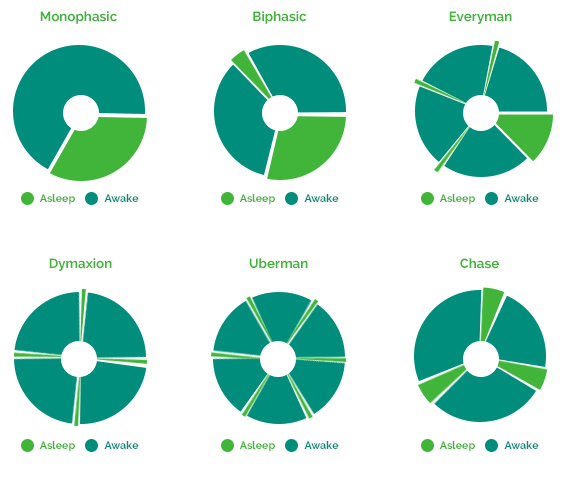

What is polyphasic sleep?

It is a term referring to alternate sleep patterns that can reduce the required sleep time to just 2-6 hours daily. It involves breaking up your sleep into smaller parts throughout the day, which allows you to sleep less but feel as refreshed as if you slept for 8 hours or more.

Simply put, it’s a series of fine-tuned power naps that allow you to sleep effectively, rest better and perform at optimum energy levels during the day.

Additionally, NeuroOn monitored polyphasic sleep allows you to sync your body clock to very demanding schedules at whatever time is convenient or required.

In conclusion, through great sleep efficiency, Polyphasic sleep can give you an extra 4 hours of free time every day. That’s up to 28 hours (1 day+) a week, 1460 hours a year.

That’s right – Your year now has over 420 working days!

Trust the masters

So, you’ve heard of Leonardo? No, not the turtle!

Apparently Da Vinci, Tesla, Churchill and even Napoleon used polyphasic sleep to rest. It allowed them to fully regenerate, reducing sleep time to 6.5 hours or sometimes just 2 hours. And those guys got things done!

A Big Fat Crisis

From: http://www.foodpolitics.com/2013/12/weekend-reading-a-big-fat-crisis/

Weekend reading: A Big Fat Crisis

Deborah A. Cohen. A Big Fat Crisis: The Hidden Forces Behind the Obesity Epidemic—And How We Can End It. Nation Books, 2013.

Here’s my blurb:

Deborah Cohen gives us a physician’s view of how to deal with today’s Big Fat Crisis. In today’s “eat more” food environment, Individuals can’t avoid overweight on their own. This extraordinarily well researched book presents a convincing argument for the need to change the food environment to make it easier for every citizen to eat more healthfully.

And from the review on the website of the Rand Corporation, where Deborah Cohen works:

The conventional wisdom is that overeating is the expression of individual weakness and a lack of self-control. But that would mean that people in this country had more willpower thirty years ago, when the rate of obesity was half of what it is today. Our capacity for self-control has not shrunk; instead, the changing conditions of our modern world have pushed our limits to such an extent that more and more of us are simply no longer up to the challenge.